The rate at which global greenhouse gases (GHGs) have been increasing in recent decades is beginning to slow, and all the technology and policy tools needed for the deep reductions needed to keep global warming below the tipping point are ready to use now.

That’s the glimmer of hope offered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Working Group 3 (WG3) report, released two weeks ago.

But aggressive action is needed now to stop the rise of emissions by 2025 and then reduce them 27 per cent by 2030, or the goal of limiting global warming to 2 Celsius or below will have moved beyond the world’s grasp, the WG3 warns in its report. To stay within 1.5 C, emissions would need to fall by 43 per cent by 2030.

“There are more and more countries whose emissions are going down,” said Simon Fraser University (SFU) sustainable energy economist Mark Jaccard, one of the authors of the Working Group 3’s policy chapter.

“This is heartening because it says some countries now – even with growing or stable populations but growing GDP – are able to get emissions declining. It’s over 20 countries by now. It’s significant.

“The bad news is, of course, we’re nowhere near being on track for 1.5 Celsius. Therefore we need to make deep cuts quickly.”

Renewable energy is just one of many technology approaches for reducing GHGs, and according to the latest WG3 report, it’s the one that’s having the greatest success in terms of adoption and costs.

“Renewables costs just keep dropping,” said Chris Bataille, who is also an SFU energy and climate policy expert and contributor to the IPCC’s WG3 report. “Where we thought – in 2015 – that we’d be in 2030, we are now in terms of costs, which transforms everything.”

Canada’s grid is already relatively clean, thanks to hydro and nuclear power, so there hasn’t been as much investment in wind and solar in Canada as in other countries.

But as greater electrification of transportation, industry and buildings takes places, all provinces will need more electricity, so there will be room for more investments in renewables like wind and solar power, as well as nuclear power.

“Depending on the region, you’re looking at an increase of 50 per cent to 200 per cent in electricity use,” said Bataille.

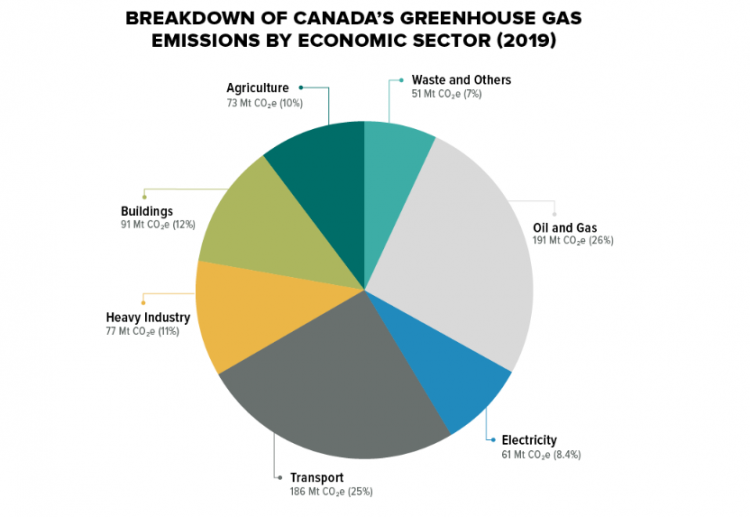

But the two biggest and most urgent challenges for Canada are transportation and oil and gas sector emissions.

So what is Canada’s plan and how does it match up with what the IPCC WG3 report?

One week before the WG3 report was released, the Justin Trudeau government unveiled its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP). It includes $9 billion in targeted funding for certain key sectors and $2.6 billion worth of investment tax credits for carbon capture and storage.

While much of the 2030 ERP relies on carrots – i.e. government incentives and subsidies – it also includes some sticks for the oil and gas and transportation sectors. The plan calls for a 42 per cent reduction in Canada’s oil and gas sector by 2030 – something Jaccard thinks would be difficult to achieve.

He said he would be happy to see oil and gas sector emissions fall 20 per cent by 2030 and thinks that can be achieved with strict methane regulations and carbon capture and storage. The latter will require some significant government subsidies and incentives, he said.

“If Canada got between a 30 per cent and 40 per cent aggregate reduction by 2030, and if emissions from oil and gas went down 20 per cent as part of achieving that target, I would be thrilled,” Jaccard said.

Bataille said the easiest and most cost effective mitigation measure for the oil and gas sector is eliminating methane leaks which account for 21 per cent of Canada’s oil and gas sector GHG emissions.

Bataille points to B.C., which has already achieved comparatively low methane emissions in the natural gas sector through regulation and best practices.

“Go after those first,” Bataille said of methane emissions. “Because we have the technology today – it’s a matter of applying it. This is all stuff we know how to do. Get those emissions down and do it fast.

“What the underlying report says in the IPCC is that we can get 50 per cent to 80 per cent reductions in global fugitive emissions for less than $50 a tonne.”

Canada’s carbon tax is now at $50 per tonne and will hit $95 by 2025, so there is a market mechanism that should encourage some companies to address methane leakage.

The federal 2030 ERP provides research funding and investment tax incentives for carbon capture and storage (CCS) – something environmental groups are already characterizing as a subsidy that may forestall the fossil fuel industry’s decline.

But the WG3 report identifies CCS as an important mitigation tool.

“CCS is an option to reduce emissions from large-scale fossil-based energy and industry sources, provided geological storage is available," the WG3 report states.

Alberta has both sufficient geological storage capacity and a dedicated CO2 pipeline that will allow upgraders, refiners and heavy industries to tie into it.

Another sector that will need CCS or carbon capture is heavy industries, Bataille said.

“Where it’s critical is going to be in cement and chemicals. It’s not really needed for steel.”

He added that substitution of other materials could dramatically reduce the use of steel.

“It looks like, over many decades, we can get up to 40 per cent reductions in steel use and 20 per cent reduction in cement use, just by designing things better,” Bataille said.

Carbon capture and use is already being demonstrated in B.C. at a Richmond cement plant through a collaboration between LaFarge Canada and Svante.

Whether it is CCS, methane reduction or electrification, all of the tools needed to get emissions down are available now, Jaccard said.

“We have the technologies, but they don’t happen without policy,” Jaccard said. “The policies you need in any jurisdiction are carbon pricing and rising stringency regulations.

“The good news is that in Canada, and especially in British Columbia – but now even Canada-wide, since the Trudeau government came into power – we have the portfolio, the mix of policies applied right across the country.”

Kevin Andrew, an economist with the University of Victoria’s Gustavson School of Business, co-authored a study that found Canada to be a leader among G20 countries in “green” stimulus spending (4th out of 19 countries).

He said Canada’s new 2030 ERP is “credible,” though he points out some regulatory policies, like a cap on oil and gas emissions and a Clean Electricity Standard, are not yet in legislation.

“They are announced policies that are not legislated,” he said. “We need to see these regulations implemented quicker if we’re going to meet this goal by 2030. We don’t have five years consultation on this oil and gas cap. It needs to get implemented within a year or two. We don’t have time to waste.”

A federal emissions reduction plan primer

Canada and other countries are aiming to reach Paris Agreement net-zero emissions targets over a span of 30 years. But the next few years is when the rubber really hits the road, as Canada aims to achieve a 40 per cent reduction by 2030.

The most important tool – federal carbon pricing – is already in place. Between now and 2025, carbon taxes in Canada will rise from $50 per tonne of CO2 to $95. The federal government’s recently released 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) implements key policies, regulations and subsidies intended to get steep reductions in the next eight years.

B.C. is already largely aligned with the plan, since it took the lead in climate policies that are only now being adopted nationally, including carbon taxes, low-carbon fuel standards, a zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate and methane reduction regulations.

Most of the policies in the 2030 ERP are carrots – incentives, subsidies and voluntary action – as opposed to sticks in the form of regulations.

The sector that will be hardest hit by new regulations is oil and gas, which will have targets and caps, and the two provinces with the heaviest lifting to do are Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Here are the ERP’s key policies, by sector, with each sector’s current share of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs).

Oil and gas: 26 per cent

The plan includes methane reductions targets of 75 per cent below 2012 levels by 2030 and a cap on GHG emissions overall, though the cap is not yet in force through legislation. There is a new investment tax credit, worth $2.6 billion, to cover some of the costs of adopting carbon capture and storage.

Transportation: 25 per cent

Heavy-duty trucks account for about a third of Canada’s transportation emissions and will be the hardest to decarbonize. Increasing carbon taxes are expected to persuade consumers, businesses and sectors to switch from gasoline and diesel to battery electric, hydrogen fuel cells or carbon neutral biofuels. The ERP includes a zero-emissions mandate for light-duty vehicles, something B.C. already has. It also seeks to raise the percentage of zero-emission vehicles among new medium- and heavy-duty truck sales to 35 per cent by 2030, but regulations mandating sales will vary depending on vehicle type and “feasibility.” The ERP includes $400 million to build 50,000 new EV charging stations. Aviation, marine and rail transportation are not subject to regulations.

Buildings, 12 per cent

The plan promises a net zero strategy for buildings for 2050, and promises new standards, but relies largely on financial incentives for things like energy efficiency, building retrofits and energy switching (for instance, from natural gas to electricity). It earmarks $875 million for an array of programs for decarbonizing buildings.

Heavy industry,11 per cent

Heavy industry includes mines, pulp and steel mills, smelters, cement plants and chemical and petrochemical plants. There is no emissions cap for industry. The main lever is carbon taxes. The ERP also includes $8 billion for a Net Zero Accelerator fund aimed at aiding industrial decarbonization approaches like carbon capture and electrification.

Agriculture, 10 per cent

There is $900 million in incentives to promote climate-friendly practices like rotational grazing, cover cropping, regenerative agriculture and methane capture and buying low-emission vehicles and equipment, but there are no regulations proposed for agriculture.

Power utilities, 8 per cent

The federal clean electricity standard (CES) will require all power generation in Canada to be zero emission by 2035. This suggests provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan that may have planned to replace coal power with a mix of wind and solar power backed by natural gas may need to include carbon capture or renewable natural gas. Nuclear power is also an option. The ERP commits to implementing a small modular reactor action plan.