We want to begin by acknowledging Premier John Horgan’s announcement that he will be stepping down in the fall. Although we have not always agreed with the policies adopted by his government, we appreciate his leadership through the pandemic as well as his longstanding commitment to public service. We wish him well.

Even as more economic forecasters and business leaders worry about the prospect of recession, the fact remains that the job market in both Canada and B.C. remains drum tight. In B.C., employment rebounded rapidly after the COVID lockdowns and then continued to advance at a healthy clip before moderating more recently. The recovery was sufficient to push the provincial unemployment rate down to near-record lows. Moreover, the number of job vacancies has soared as employers in multiple sectors scramble to fill positions. These high-level metrics suggest the province’s labour market is healthy, with no signs of a material softening.

But the foundation of the employment revival is not as sturdy as it initially appears. Our monitoring finds that employment has regained and surpassed pre-pandemic levels in just eight industries. It remains below pre-pandemic levels in another seven industries and is unchanged in one. Approximately 188,000 jobs have been created across the eight “growth” industries since early 2020. But employment is down by 85,000 across the harder-hit industries, leaving net employment in B.C. up just 100,000 – a cumulative 3.9 per cent rise over almost two-and-a-halfyears. Over the comparable 28-months between 2016 and mid 2019, job growth averaged more than seven per cent. Given this context, the current “28-month” employment growth rate should be viewed as modest at best.

Digging deeper into the data reveals that more than 90 per cent of the job gains since February 2020 have been concentrated in six industries. Health care and social services alone added 50,000-plus positions.

Another 40,000 have been created in professional, scientific and technical services – a large and important private sector industry. There have been 25,000 net new positions in public administration. Employment in education has risen by almost 19,000 in the last 28 months, with smaller gains of 15,000 or so in the manufacturing and information, cultural and recreation industries.

Three of the six industries reporting meaningful job increases are fully or mainly staffed by public sector workers. Labour market data confirms that the public sector accounts for an unusually large share of job growth in the province. Public sector employment is up 75,000 since February 2020, with the remaining 25,000-plus new jobs scattered across the private sector. This means that three of every four net jobs created in B.C. have been in the public sector.

During the pandemic, the labour market dynamics have differed from normal, to say the least. Had the main trends evident in the decade before the pandemic persisted, total employment would be 60,000 higher than it is currently. Private sector employment would be 110,000 higher, while public sector employment would be 50,000 lower.

If the labour market recovery were more closely aligned with past trends, public sector jobs would have grown at an annual rate of 2.3 per cent, instead of the 6.8 per cent recorded since February 2020. Private sector jobs would have advanced at an annual rate of 2.7 per cent, compared with the anemic 0.6 per cent pace we have experienced.

Thus, British Columbia has seen a rather marked rotation towards public sector employment in the last 28 months. The expanding public sector played a pivotal role in the employment rebound that government ministers are fond of talking about. The pace of public sector hiring will doubtless slow from its recent breakneck clip. But what is concerning is that even a mild recession will quickly put downward pressure on private sector employment – likely resulting in tens of thousands of outright job losses. This means the looming economic slowdown/downturn will further reinforce the pandemic-related shift towards public sector employment.

An economy in which the public sector accounts for the bulk of job creation over an extended period will become both unbalanced and financially unsustainable. Ultimately, private sector firms and their employees must provide most of the tax revenue needed to pay for public services and public sector jobs. B.C. policymakers would be wise to remember this – and to devote more of their energies to fostering a business climate that supports private sector hiring and the growth of local companies. •

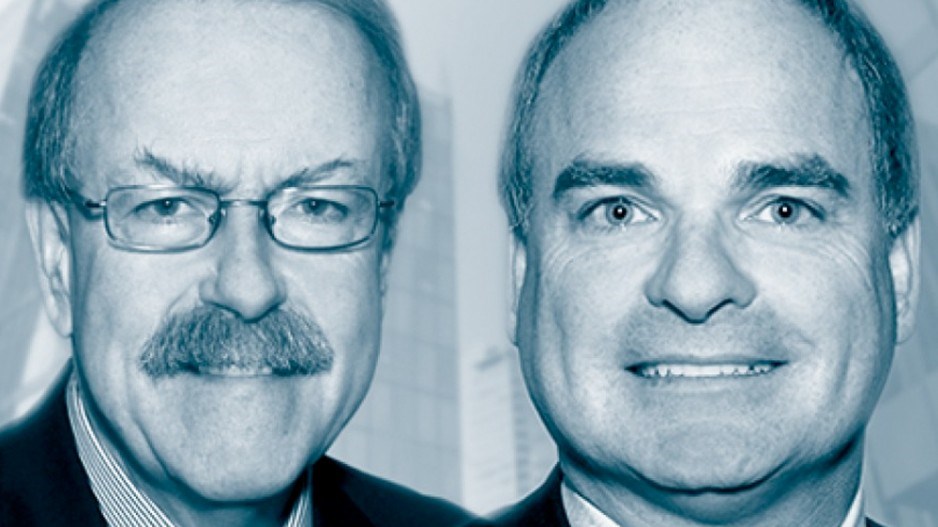

Jock Finlayson is the Business Council of British Columbia’s senior policy adviser and senior fellow at the Fraser Institute; Ken Peacock is the council’s senior vice-president and chief economist.