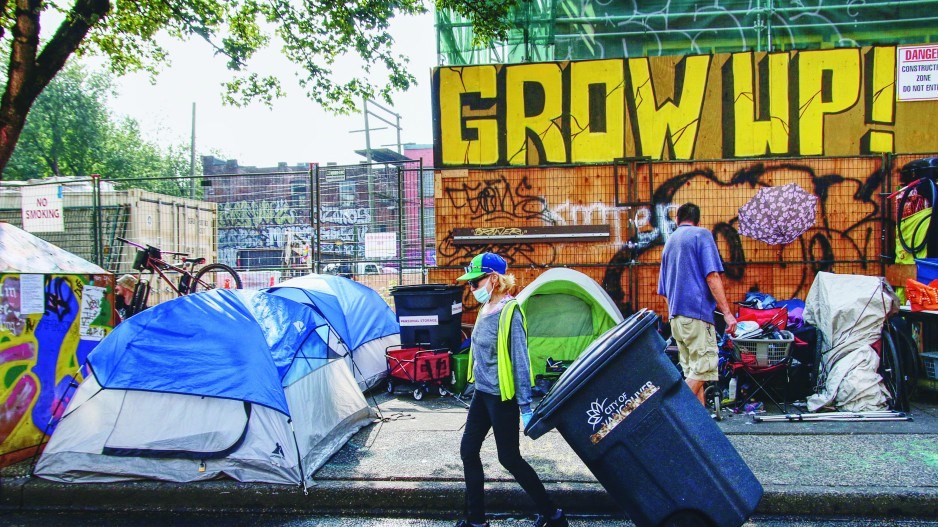

Random stranger assaults, gratuitous vandalism, organized group shoplifting, addicts in fentanyl freezes in doorways, tent-filled city streets resembling set pieces from a post-apocalypse movie, overdose deaths at a rate of six a day.

The signs of social decay and disorder can be seen in cities across B.C., but nowhere are they more acute or visible than in downtown Vancouver. Some residents no longer feel safe walking down the streets where they work and live.

Concerns about crime and security linked to drug addiction, homelessness and untreated mental illness now rank as the third most pressing issue among businesses and ordinary citizens in Metro Vancouver, according to recent polling by the Mustel Group and Research Co.

For some businesses, it’s the No. 1 issue, said Teri Smith, executive director of the West End Business Improvement Association and president of the Business Improvement Areas of BC (BIABC).

“This has become the forefront issue for us,” Smith said. “We’ve definitely noticed and heard about increases in crime. A lot of property crime – smashed windows, a lot of graffiti, break-and-enters – and there’s been a lot of concern around increasing aggressive encounters between small business owners, their employees and individuals that are coming into their places of business.”

“The erosion of social contracts is evident everywhere you look, with broken windows that lead to boarded up windows, graffiti stamped everywhere on both public and private buildings and spaces, and prolific shoplifters caught, released and caught again all in the same day,” said Walley Wargolet, executive director of the Gastown Business Improvement Society.

In Chinatown recently, a security guard was viciously attacked, a business owner was pepper-sprayed and robbed and a meal delivery worker was stabbed multiple times in an apparent random, unprovoked attack.

Some seniors living in the area are now afraid to go outside, said Jordan Eng, president of the Chinatown Business Improvement Area Society. He said city hall does not appear to be taking concerns about crime in the area seriously.

“We had a lot of lip service over the last four years,” he said.

There is growing frustration with police and city hall for not enforcing laws and bylaws to prevent street crime and disorder from festering.

“If someone is passed out on the street, you take him off the street and put him in detox,” Eng said. “It seems like, right now, the only intervention is once a person has overdosed.”

“We’re not seeing police out walking the streets – they’re sitting in cars,” said Nolan Marshall III, president of the Downtown Vancouver BIA. “From the municipal side, we’re not seeing the municipal bylaws enforced in terms of where people can sleep and during what hours.”

There is a sense among some business owners that part of the problem in Vancouver is that police are getting neither the financial nor moral support they need from city hall.

“The problem is definitely with the leadership at the city hall,” Eng said. “There are councillors that support the police. We’re into an election, and the mayor’s now saying that he supports the police, even though he has a history of not.”

When city council denied the Vancouver Police Department’s (VPD) request for a $5.7 million bump to the police budget for 2021, B.C.’s Director of Police Services ordered the city to put the funding in its budget. But as a result of the city’s decision not to fully fund the VPD, the force was unable to hire 61 new recruits.

Police may be frustrated that they are being discouraged by city hall from doing their jobs. When they do arrest repeat offenders, the offenders are often quickly released, without adequate support or rehabilitation, thanks to a catch-and-release criminal justice system.

The BIABC last week issued a plea to all three levels of government to do something about crime and “street disorder.”

At the municipal level, the BIABC is challenging mayoral and council candidates across B.C. to commit to addressing street crime and disorder with more funding for policing, enforcing local bylaws, improving sanitation and providing more street lighting.

As a result of surging crime and general street disorder, some Vancouver municipal candidate slates now have platforms highlighting public safety.

The Non Partisan Association, led by a mayoral candidate who is a former police officer, has a 19-point public safety plan that includes reviewing the Downtown Community Court to address what it calls a “revolving door” of petty crime offences.

TEAM for a Livable Vancouver proposes creating a full-time Downtown Eastside commissioner “with a mandate to address the out of control social issues that are impacting the health and safety of the community.”

ABC Vancouver has pledged “on Day 1” to expand a program, Car 87, that pairs cops with mental health practitioners by adding 100 new police officers and 100 mental health nurses.

That may be easier said than done, said pollster and political observer Mario Canseco of Research Co., who points out that ABC would need a majority on council to make good on such a promise.

“It requires co-ordination with several layers of government,” Canseco added. “The city can’t hire nurses unless it deals with a specific provincial health authority.”

Even so, the promise of additional police resources is something that may resonate with businesses. The BIABC is calling for increased policing resources across B.C.

And B.C. mayors are asking for sentencing reforms to ensure prolific repeat offenders either go to jail, or get treatment for drug addiction and-or mental health disorders.

In April, the BC Urban Mayors’ Caucus – a group of 13 mayors in B.C. – called on the provincial government to bring in stronger bail conditions and harsher sentencing for prolific offenders.

B.C. Attorney General David Eby said he would study the request.

“That is a failure of the B.C. government,” said Anita Huberman, president of the Surrey Board of Trade. “There’s been so many studies already done. The time for studies is over. They need to implement action right now.”

Crime-fighters seek seats on city council

Two candidates running for Vancouver city council have some unique insights and expertise on policing and crime, which have emerged as significant municipal election campaign issues.

One is a former Vancouver cop, the other a senior crime analyst for the Vancouver Police Department (VPD).

Brian Montague, a 28-year veteran of the VPD, is running for council under the ABC Vancouver slate. Arezo Zarrabian, a crime analyst whose focus in recent years has been Vancouver’s city core, is running for the Non Partisan Association.

While they are running on different slates, they agree on a few things:

•Crime and disorder in downtown Vancouver have spiked in the last couple of years;

•police are not adequately funded;

•a housing-first policy that isn’t properly backed with wrap-around supports doesn’t work; and

•the courts are failing to protect citizens from prolific repeat offenders.

Zarrabian was the VPD analyst who identified a new trend emerging in the fall of 2020 that came to be known as stranger assaults: Violent, unprovoked assaults in which the perpetrator doesn’t know the victim and where robbery isn’t a motive.

“We saw a huge trend, starting after [fall] 2020, in violent shopliftings as well,” she said. “It was an organized shoplifting, similar to what we’ve seen in San Francisco, Seattle. It’s almost like they have a list. They’ll walk into the Lululemon (Nasdaq:LULU) and they’ll take $1,000 of merchandise. The weapons usage has increased, too, in the last two years in the downtown core.”

Citing recent VPD crime statistics, Zarrabian said assaults were up 20% in July, compared to July 2021, robberies up 56% and sexual assault up 13%.

“We have seen double-digit increases from 2021,” she said.

Part of the problem may be a lack of front-line police officers.

“Our authorized strength at the Vancouver Police Department has not moved since 2009 … whereas our (population) density has increased significantly since 2009,” Zarrabian said. “We were operating at minimum for certain shifts. We didn’t have the strength of having full teams out around the city, and this does play into this greater picture of the crime going up.”

Montague, who retired from the VPD four months ago, said police feel they do not have the backing of city hall. In some cases, police feel they are discouraged from doing their jobs, like evicting people from homeless encampments.

“The city has made it very clear that they don’t want that happening,” Montague said.

When police do make arrests, criminals are often sent right back onto the street to re-offend, either because prosecutors won’t prosecute or judges refuse to hand out jail sentences or order repeat offenders with drug addiction or mental health problems into supervised treatment.

Montague said the VDP identified 40 offenders involved in random stranger attacks.

“They looked at the background and found they were responsible for something … just a little shy of 4,000 police calls for service,” Montague said. “I personally know an individual that has over 100 convictions and that continues to be arrested.

“If the city doesn’t want the police policing certain things, if the prosecution services won’t lay charges, why are the police wasting their resources?”

Zarrabian agreed that revolving-door justice is a problem.

She cited one case in which a repeat offender one morning caused $100,000 in damage, mostly broken windows, was arrested and released in the afternoon on a promise to appear.

“Within an hour of being released, he went to a different neighbourhood in the downtown core, and he did another $25,000 worth of damage,” Zarrabian said. “That’s one day. That’s not a policing issue – that is a court issue. That is the lack of having teeth in the justice system.”

Montague and Zarrabian both agree that enforcement alone won’t fix urban crime issues. They say municipal, provincial and federal governments have failed to provide the “wrap-around” services needed to deal with the mental illness and drug addiction that are so often behind criminal recidivism. The housing-first approach only works if all the other services needed are there.

“We need enforcement, and we need mental health facilities, and we need drug addiction treatment, and we need social and supportive housing,” Montague said. “All that’s happening now is harm reduction.”

“There’s no point of giving housing to individuals that need complex care if you’re not going to give them the complex care in that housing unit,” Zarrabian said. “All you’re doing is creating a warehouse situation with individuals, and all that does is create more victimization with those units.”

She doesn’t buy the argument that those sorts of support services are mostly senior government purview and therefore beyond the scope of municipal councils.

“They have the ability to push the federal government for housing money,” she said. “So don’t tell me they don’t have the push to address the other issues that are just as important as housing.”

(Update: The Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General released an action plan September 21 to address concerns over crime, including prolific offenders. It includes a recommendation to the BC Prosecution Services to consider increased use of "therapeutic bail," in which delayed sentences are granted to offenders with mental health or drug addiction issues while they get treatment, and which can result in them avoiding criminal convictions.)