The final week of summer is a good time to step back and assess developments in the job market and how it has evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic relative to expectations that prevailed before 2020.

Even as economic activity slows and the job market loses momentum, labour market conditions in B.C. remain unusually tight. Total employment is up almost three per cent per cent since the start of 2020, a somewhat anemic increase over a two-and-a-half-year period. Of concern is that public sector employment is up an astonishing 18 per cent over the period while payroll employment in the private sector has barely advanced (1.7 per cent). The number of self-employed declined, so the total number of jobs in the B.C. private sector, as of August, is slightly lower than just before the pandemic.

Yet, despite feeble job gains in the private sector (which accounts for the bulk of all jobs in the province), the provincial unemployment rate sits near a record low. Employers in most sectors are scrambling to attract and retain labour. In aggregate, there are now more job vacancies in the province than people looking for a job, an imbalance rarely if ever seen until about a year ago. The all-industry job vacancy rate stands at 6.1 per cent; some sectors report double-digit vacancy rates. Finding employees is a major preoccupation in many B.C. industries.

In some ways, the onset of worker scarcity is a surprise. In the five to six years before the pandemic, a belief took hold that automation, artificial intelligence, the spread of robots and other developments associated with the “fourth industrial revolution” would upend labour markets and lead to many tens of millions of jobs disappearing quickly across the advanced economies collectively. A much-discussed academic paper published in early 2017 estimated that 45 to 47 per cent of all jobs in advanced economies were at “high risk” of disruption owing to automation and the adoption of other digital technologies.

Closer to home, our colleague David Williams, writing in 2018, found that applying the same methodology used in the just-cited paper pointed to 42 per cent of jobs in B.C. having a “high probability” of being fundamentally changed in the next two decades. A major study from the McKinsey Global Institute, released a few years before the pandemic hit, predicted that intelligent agents, robots and other digital technologies could eliminate the need for 30 per cent of all “human labour” and displace up to 800 million jobs worldwide by 2030.

From today’s vantage point, projections of sweeping job losses/disruption look premature. Provincial labour market data suggests a scarcity of workers is constraining private sector employment growth, and that at least to some extent public sector hiring is crowding out private sector hiring. B.C.’s low unemployment rate, high job vacancy rate and stronger wage growth does not align with the spectre of a current or imminent tsunami of technology-driven job destruction rolling across large swathes of the economy.

Before the pandemic, we sometimes encountered stories suggesting jobs for truck and bus drivers were especially at risk as self-driving vehicles replaced those reliant on human beings. Today, media reports talk of shortages of truck drivers as one of the factors hindering the recovery of supply chains impacted by COVID-19, while transportation providers such as TransLink in B.C. struggle to fill positions for transit operators. The dramatic shift to work-from-home (WFH) in 2020 and 2021 underscored the crucial role of digital technologies and platforms in enabling workers and employers to adjust to and innovate amid the COVID-19 shock. But so far, there is little evidence that the persistence of remote work models is depressing the overall demand for labour – including in industries where WFH has proved to be most popular.

Far from the arrival of the digital economy heralding a dystopian “end of days” scenario for hundreds of millions of workers, today labour seems to be in short supply. Even with elevated vacancy rates and wages and salaries climbing more quickly (albeit often not sufficiently to match recent inflation), there is little evidence companies are suddenly making much greater use of labour-saving technologies.

Looking ahead, the march of technology will undoubtedly lead to many job losses and perhaps painful dislocations in some segments of the labour market. But the key question is over what time period such changes unfold. Our suspicion is that technology-enabled labour displacement, while powerful, will be incremental. This suggests that the economy and the labour market will have time to adjust as the “fourth industrial revolution” continues to progress. ■

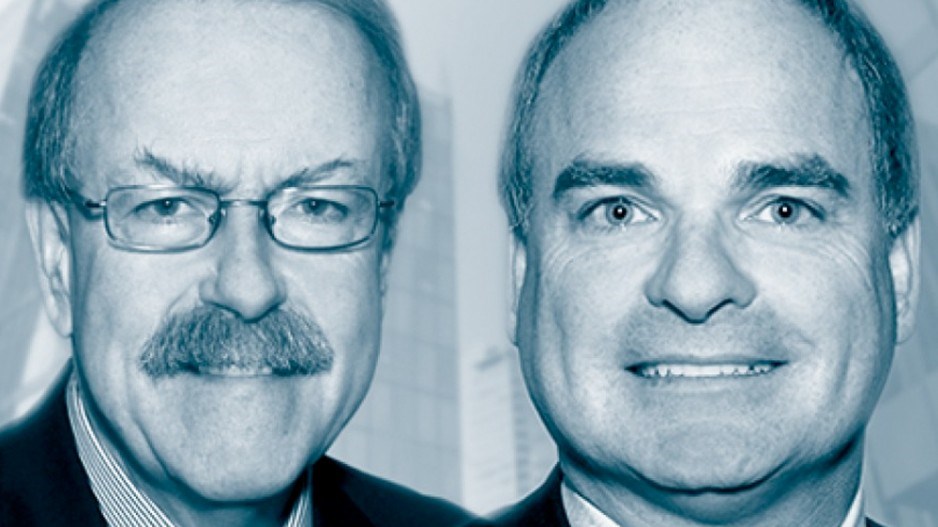

Jock Finlayson is the Business Council of British Columbia’s senior adviser; Ken Peacock is the council’s senior vice-president and chief economist.