This article was originally published in BIV Magazine's Life Sciences issue.

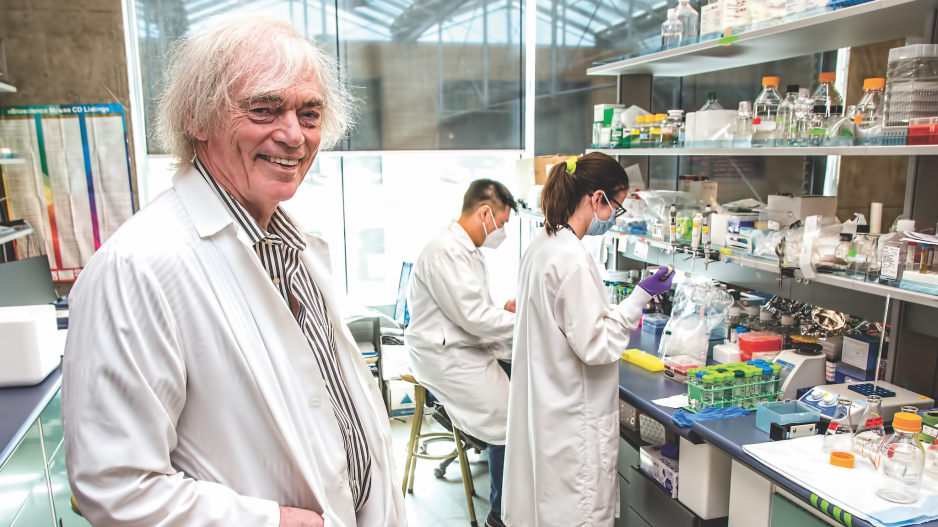

Pieter Cullis does not want to jinx his chance of winning a Nobel Prize by discussing the possibility.

The 76-year-old University of British Columbia (UBC) emeritus professor’s work was essential in helping Pfizer and BioNTech create a COVID-19 vaccine that has been injected into more than one billion people, perhaps saving millions of lives.

The biochemistry and molecular biology researcher’s work with lipid nanoparticles has helped him rack up plenty of awards and gain international recognition.

Last year, he won Thailand’s Prince Mahidol Award for medicine, along with colleagues Katalin Kariko and Drew Weissman – a prize that came with a US$100,000 cheque for the trio.

He was named an officer of the Order of Canada by the end of the year.

Cullis, Germany-based Kariko and U.S.-based Weissman then in January pocketed US$3 million as part of winning Vietnam’s VinFuture Grand Prize. In April, they won a Canada Gairdner International Award, worth $100,000, and in June, the three won Taiwan’s Tang Prize – an honour that came with a cheque for US$1.7 million, and a US$350,000 grant for future research.

Tang Prize winners are selected by a committee of internationally renowned experts, and several past recipients have gone on to win Nobel Prizes.

“I’m not going to comment on that,” Cullis says when asked him how likely it could be for him to win the world’s premier award for scientific achievement, which comes with a cheque for 10 million Swedish Krona, or just under US$1 million.

Kariko and Weissman’s expertise was in engineering messenger RNA to be the active ingredient in the vaccine, while Cullis’ role was creating the system for getting the vaccine’s active ingredient into human cells.

He and his team at UBC have for decades worked with lipid nanoparticles, which are essentially little bubbles that encase genetic material, cancer drugs, vaccine components or other items, and transport them to specific cells without degradation.

The method is somewhat like a security team transporting an important dignitary through a crowd of rowdy protesters to a key destination.

It is a complex task.

“You have to find a way to have [the encased material] be taken up into a cell, and then into the cytoplasm,” Cullis says, referring to the gelatinous liquid that fills the inside of human cells.

“That was the puzzle that we managed to solve.”

Recognition and awards follow decades of work

Born in England, Cullis moved to West Vancouver with his parents when he was eight years old.

The West Vancouver High School graduate completed his bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and a PhD in physics all at UBC before moving on to study at London’s Oxford University for a four-year post-doctoral fellowship.

“The time at Oxford was in biochemistry so it was a big switch from physics,” he says.

He also briefly conducted research at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands before returning to UBC as an assistant professor.

Mick Hope, who was a fresh PhD graduate when he met Cullis at the University of Utrecht, says Cullis made an immediate impression.

“He was different from anybody else that I’d come across in the science field up to that point,” says Hope, who went on to found several companies with Cullis.

“He was obviously incredibly intelligent, but he was able to focus. He has so many ideas and he knows how to implement those ideas, and he doesn’t take no for an answer. He’s not easily distracted.”

Hope says Cullis’ incredible work ethic shone through even back at Utrecht.

The two would pull all-nighters because needed equipment was sometimes only available late at night and in the wee hours of the morning.

“We would do a 24-hour shift, and then go back home and sleep, and then come back and do another,” Hope says.

The work paid off because it helped the two generate data quickly, publish papers and gain name recognition in the scientific community.

Cullis says he was encouraged to apply for a posting at the University of Nebraska, but he looked at the map and realized that the move would not be the right fit for someone who loves the West Coast, and the ocean.

He considers himself lucky to have won a large grant in the late 1970s, and find an assistant professor job at UBC. He then encouraged Hope to come to Vancouver to join his biochemistry research group.

Lipid nanoparticles were that group’s focus from Day 1.

“The basic research I was doing was on the physical properties and functional roles of lipids in biological membranes,” Cullis says.

“Biological membranes are pretty important. You have 30 trillion cells in your body, and each one is surrounded by a membrane.”

The lipids are about 100 nanometres long (or about 1/100,000th of a millimetre) and are like bubbles, as they are the permeability barriers that separate the insides and outsides of cells, he explains.

By the mid-1980s, Cullis’ team had devised a way to make lipids using what he calls an external stimuli extrusion technique, and they developed a machine to do this work.

They needed no human material to create the lipids.

This led to Cullis in 1985 co-founding his first company, along with Hope and Thomas Madden: Lipex Biomembranes, which marketed a device that Cullis calls the extruder. That venture would later morph into Northern Lipids.

“We found a way to load these things with cancer drugs,” Cullis says. “That really triggered the first therapeutic endeavours, which were to try to package up cancer drugs and direct them specifically to tumor sites.”

Work with cancer led Cullis, Hope and Madden to co-found the Canadian Liposome Co., which was a subsidiary of Princeton, New Jersey-based The Liposome Co. Inc.

There, the team developed two main drugs – one focused on breast cancer, and another that targeted fungal infections that often affect people undergoing cancer therapies.

A new CEO took charge at The Liposome Co. and demanded that Cullis and his team relocate to New Jersey. That prompted Cullis’ team, in 1992, to abandon the Canadian Liposome Co., and set up a new Vancouver-based venture: Inex Pharmaceuticals, which continued to focus on cancer-fighting drugs.

The team then shifted to focus on gene therapies because they found it easier to raise money for that research.

The pivot essentially meant that the company added a line of research that involved putting DNA and RNA compounds in the lipid nanoparticles instead of what had been cancer-fighting compounds, Cullis explains.

It was around 2005 when Cullis embarked on a side project, and helped create UBC’s non-profit Centre for Drug Research and Development, which has since rebranded as AdMare Bioinnovations. The organization has helped build Canada’s life sciences sector ecosystem.

Cullis’ gene-therapy work went into overdrive that same year, when his team linked with Massachusetts-based Alnylam Pharmaceuticals to develop an RNA drug that could suppress a faulty gene in liver cells.

By then, they had left Inex Pharmaceuticals, which had floundered after a US Food and Drug Administration committee rejected Inex’s lead product, Marquibo, for accelerated approval, causing Inex’s share price to plunge more than 86 per cent in a day in December 2004.

In 2007, Inex became Tekmira, and then rebranded as Arbutus Biopharma Corp. in 2015.

Cullis, Hope and Madden’s next venture was Acuitas Therapeutics, which they founded in 2009. It wasn’t long before they heard from a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania: Weissman.

He wanted to use Acuitas’ system to deliver vaccines to cells, starting with experiments for a vaccine for the Zika virus.

“It turned out that that worked really well,” Cullis says.

“The work has not turned into a [Zika virus vaccine] product yet but it will. What the work did was demonstrate that these systems can be very effective vaccines, and it triggered a partnership between Acuitas and BioNTech.”

That Acuitas-BioNTech partnership involved Kariko, who is BioNTech’s senior vice-president. Work largely focused on creating flu vaccines, in part because the need was greater and there was more money to be made in developing flu vaccines than Zika virus vaccines, Cullis says.

Perfectly poised to help address COVID-19 pandemic

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, all efforts pivoted to developing a COVID-19 vaccine.

The timing was impeccable, as Acuitas was perfectly poised to help the world fight off a pandemic that has caused millions of deaths.

“Sometimes you get lucky,” Cullis says with a laugh.

The privately owned Acuitus licensed its intellectual property to BioNTech and cashed in on demand for the COVID-19 vaccine.

“Acuitas has done pretty well out of this,” Cullis says, without giving specifics on the company’s financial situation.

“Obviously, when there’s billions of dollars in sales, this is where the lawyers get involved.”

Indeed, plenty of lawsuits are yet to be decided.

Acuitas earlier this year filed a lawsuit against Arbutus – Inex Pharmaceuticals’ successor company – and Genevant Sciences GmbH to ward off a legal challenge that Arbutus and Genevant had threatened to launch against Pfizer.

What prompted the suit was that Arbutus and Genevant, in March, filed a lawsuit against Moderna Inc., alleging that patents for its inventions were infringed.

The innovations in question relate to lipid nanoparticle activity.

“There’s a whole lot of litigation going on – Alnylam has filed lawsuits against Pfizer and Moderna,” Cullis adds.

Despite being well past retirement age, Cullis does not foresee himself quitting scientific research.

He simply enjoys it too much.

Cullis no longer teaches at UBC but his status as professor emeritus enables him to keep working at his on-campus lab.

“It’s basic research,” he says.

“One of the areas I’m really fascinated in is what we call triggered release. With a cancer drug, for example, the problem is that while we can package up these cancer drugs in lipid nanoparticles, we can’t get them to come out in the places that we want them to come out, such as the region of a tumor.”

He resigned as Acuitas’ board chair last year, although he still owns shares in the company.

Cullis has recently shifted his attention to launching NanoVation Therapeutics, which has a platform to enable gene therapy.

Friends say Cullis is not all work, and that he has a fun and playful side.

Hope says Cullis and his team would regularly book venues and hold large parties whenever one of them reached a birthday milestone, such as 40 or 50 years.

The parties got bigger as the years went by, Hope says.

“We’d often have skits,” he says. “We actually formed a ballet company called the Royal Lipex Ballet, and we would do dances – all dressed in tutus. So that was kind of quirky.”

Jay Kulkarni was a PhD student working under Cullis nearly a decade ago. He tells BIV that he and Cullis would sometimes disagree on the likely outcome of experiments.

Cullis would then suggest that whoever was wrong would owe the other a beer, Kulnarni said.

Cullis confirmed that these bets took place.

“He owes me a lot of beer,” Cullis says with a laugh.

B.C. executives across the life sciences sector recognize Cullis as one of the most significant people to have worked in the field.

“He’s been sort of that father figure, that godfather-founder,” says former Zymeworks CEO Ali Tehrani, who is now a venture partner at Amplitude Ventures.

“I would put him in the top five influential people in the B.C. life sciences sector.”

He adds that Cullis has a good chance of eventually winning a Nobel Prize because the impact of his work has been global in scope.

“Nobel Prizes historically have come 20 or 30 years after the fact,” Tehrani says. “Given the impact of COVID-19 around the world, I think 20 years from now somebody is going to get it.”

This article was originally published in BIV Magazine's Life Sciences issue. Check out BIV’s full digital magazine archive here.