Poseidon Acquisition Corp.’s push to acquire the Vancouver-based crown jewel of Atlas Corp. (NYSE:ATCO) is a gamble on the present and future buoyancy of the global container cargo shipping sector.

Today, that gamble looks like a good bet; tomorrow, maybe not so much.

Consider, for example, that 2022 second quarter collective net income for major ocean carriers was a staggering US$63.7 billion, according to container shipping industry analyst John McCown, which is a seventh straight quarter of record profit for a sector that in the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was navigating a sea of red ink.

McCown now projects net 2022 income for the sector to be on pace for US$245 billion or roughly 65 per cent above its 2021 net income.

As McCown noted in a recent container shipping sector revenue report, “The sharp upturn in the quarterly bottom line performance of the container shipping industry over the last two years is one of the most pronounced performance changes ever by an overall industry.”

In an interview with BIV, he said the container shipping industry now “has a higher net income to revenue margin than any individual tech company you can find. So, move over Microsoft.”

Yet McCown, who has been involved in the container shipping industry as an operator and investor for four decades, told BIV that anyone banking on ocean carriers maintaining that revenue and profit run long-term is engaging in wishful thinking.

“I mean … I certainly don’t think 46 per cent net income [as a percentage of revenue] on a revenue margin is sustainable.”

Recent shipping industry data agrees with McCown.

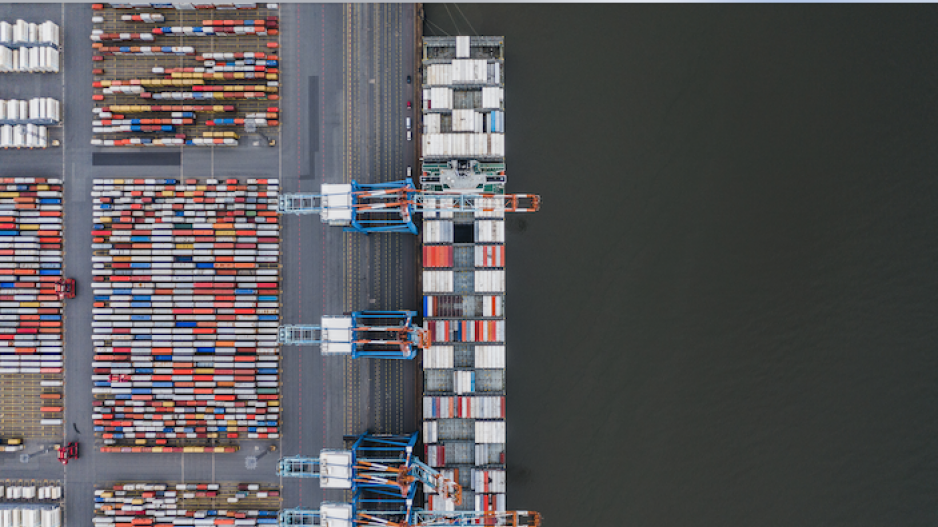

Drewry noted in a recent report that while global container cargo handling grew 6.8 per cent in 2021, it has slowed to a projected 2.3 per cent for 2022. Container ship port calls, according to the U.K.-based shipping industry consultancy, have also dropped six per cent between the first half of 2019 and the first half of 2022.

The ocean carrier industry, it concludes, is “entering a period of managed decline.” Drewry’s most recent Container Forecaster therefore poses the question: “Do carriers have the tools to mitigate the upcoming supply and demand shocks?”

Whether they do remains to be seen, but that decline has been caused by several factors. They include a consumer marketplace shift away from goods and back to tourism and other service industry options.

Inflation, global trade disruption sparked by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and higher energy prices are also contributing factors.

Seaspan, the world’s largest lessor of container ships, has benefited from the container shipping sector’s revenue bonanza.

Second-quarter revenue for Atlas, its corporate parent, was US$413 million, which was up 4.9 per cent from the same quarter in 2021. Net income was up 2.6 per cent to US$279.5 million; US$252.4 million of that income was generated by Seaspan.

Seaspan’s operating containership fleet has grown to 134 ships from zero in 2001. It also has 67 ships under construction and will have a working fleet of 201 ships with a total carrying capacity of 1.95 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) when Seaspan’s newbuilds are delivered.

It celebrated its 20th anniversary late last year with third-quarter financials that included profit up 31 per cent to US$256 million compared with the same quarter in 2020.

Atlas has a current market cap of US$3.5 billion.

So, given the present state of the container-shipping sector, the Poseidon consortium’s push to acquire Atlas in general and Seaspan in particular makes sound market sense.

It recently increased its per-share bid price to acquire all of the outstanding shares of Atlas that the consortium does not own to US$15.50 from the US$14.45 in Poseidon’s original Aug. 4 offer.

The revised Sept. 28 offer came after the special committee appointed by Atlas to consider Poseidon’s acquisition bid rejected the initial offer, which the committee said in a statement “did not reflect the standalone value of the company.”

The Poseidon consortium includes chair David Sokol, who is also the chair of the Atlas board of directors, affiliates of the Washington family, affiliates of Fairfax Financial Holdings and Ocean Network Express, the world’s sixth largest maritime container shipping company.

Together, they own more than 50 per cent of Atlas’ outstanding common shares.

Sokol said Poseidon’s increased bid price represented its final and best offer.

As of Oct. 6, the special committee confirmed that "meaningful progress" had been made in negotiations with Poseidon regarding its updated offer.

But the container shipping sector revenue bonanza reaped over the past two years has some potential downsides for Atlas and Seaspan, whose business model is to negotiate long-term leases for its container ship fleet with major ocean carrier companies.

Those container shipping companies are now flush with cash. Many are using it to pay down debt; many are also commissioning contracts for new ships to add to their fleets. And, as McCown pointed out, it is cheaper in the long run for ocean carriers to own their own ships than to lease them from companies like Seaspan.

Alphaliner, a global shipping industry data company, noted in an August report that 2.3 million TEUs of newbuild shipping capacity is expected to hit the global market in 2023, which could trigger another return to overcapacity in container shipping.

Overall, the order book for new container ships represents an additional 30 per cent of global container shipping capacity, which is currently 24.6 million TEUs.

That represents another risk for ocean carriers and container ship leasing companies.

McCown, who worked for many years with Malcolm McLean, who pioneered the transportation of maritime cargo in containers, said it will be critical to Seaspan’s continuing success to make the right bets on the size of ships it adds to its fleet to ensure they are the most efficient and cost effective for ocean carrier companies in what is an extremely volatile and competitive marketplace.

Because Asia-U.S. trade currently accounts for 25 per cent of global container miles, McCown pointed out that any major move of large manufacturing operations away from China and elsewhere in Asia to be closer to North America will result in fewer container cargo shipping miles worldwide.

Combined with a slowdown in the global economy, McCown said, “The leasing container ship model is going to be less prominent because of less growth.”

He suggested that one of the options open to Poseidon if it were successful in acquiring Seaspan would be to launch another transpacific container shipping line that handled only 53-foot cargo containers.

That size box is the maximum that trucks in North America are allowed to transport, and a service focused on it would minimize the need to pack and unpack cargo from 20- and 45-foot containers and repack them into the larger boxes once they are unloaded at port terminals.

“That would give you a distinct edge,” McCown said. •

@timothyrenshaw