This article is from the June 2023 edition of Mákook pi Sélim – an Indigenous business magazine that exclusively features articles and columns from Indigenous writers.

There are more than 230 remote communities in Canada that are powered by microgrids, and 27 of them are in British Columbia.

The majority of those 27 communities are Indigenous and have been leading advocates in the shift from a reliance on diesel as a source of power, to clean energy opportunities such as solar, wind, tidal and small-scale hydro dams.

Diesel generators are expensive, high carbon producers, and put a strain on overall health and wellness of peoples and lands. Clean energy utilizes the natural elements and energy of the lands such as the sun, wind, fire and water – sources that are more aligned with the Indigenous way of being, worldviews and values of being interconnected to nature, and living in harmony with traditional lands.

Despite broad recognition of the need to reduce carbon emissions, and support for decarbonization initiatives, a lot of this advocacy has fallen on deaf ears within government and the utilities.

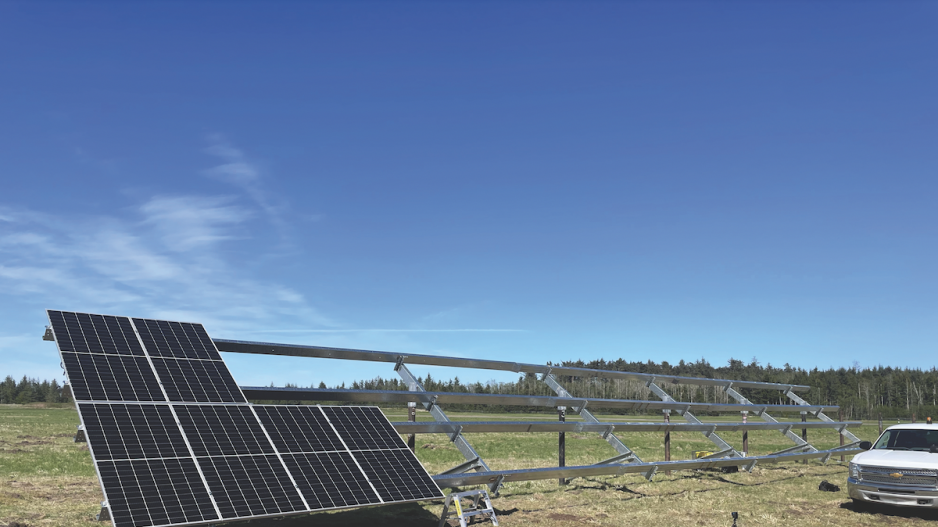

Trent Moraes is the Deputy Chief of Skidegate Band Council on Haida Gwaii, and has been leading the development of a cleaner energy grid for over a decade. The council has successfully built a two-megawatt (MW) solar field and many other clean energy initiatives.

Moraes shared that Haida Gwaii has the largest consumption of diesel among all remote communities in British Columbia.

“We are bigger than the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Alberta combined with over 51.06 per cent of all B.C.’s diesel generation in Haida Gwaii, which is 5.4 per cent of all of Canada’s diesel consumption.”

Moraes is not only leading a different energy path forward for Haida Gwaii, but has co-founded a clean energy group that represents all remote Indigenous communities (known as Non-Integrated Areas [NIA]) to advocate for decreased diesel reliance and support from provincial and federal governments, BC Hydro and the BC Utilities Commission for clean energy projects.

Despite diesel consumption being the largest opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Moraes says that “they are the last considered and this is crazy!”

He adds that “our voice hasn’t been considered until the adoption of UNDRIP,” referring to Indigenous voices and Bill 41 that was adopted by B.C. in 2019. “First Nations are now being required to be consulted with. Since UNDRIP, we are no longer an option.”

When asked what the barriers are for moving away from diesel reliance to clean energy, Moraes shares that “it’s BC Hydro and their red tape, and the BC Utilities Commission. The province must advocate and make legislative and regulatory changes to the process that will make way for Indigenous communities to lead clean energy projects in their community.”

Moraes offers some solutions to those barriers. More Indigenous people are needed inside BC Hydro to help the utility understand, relate to and connect with communities, ultimately leading to better relationships.

At BC Hydro and with the provincial and federal governments, Moraes says that there is support from top executives and ministers for Indigenous-led clean energy projects, but that it’s the bureaucracy that stalls initiatives and frustrates change.

Aligning executive and political will with bureaucratic and organizational operations would go a long way in making necessary changes, he says.

Leona Humchitt from Heiltsuk First Nation has also been leading the way for her nation with the creation of the Haítzaqv Community Energy Plan. Humchitt says that this plan was created “by the Heiltsuk for the Heiltsuk.” It incorporated a robust community engagement plan built from the more than 1,000 Heiltsuk voices that spoke about Heiltsuk history, language and culture.

“We incorporated our own language and words into the plan, and this creates ownership and buy in from the community,” Humchitt says, adding that creating the Haítzaqv Community Energy Plan “was an amazing journey that helped us blossom and root ourselves in stronger jurisdiction.”

Similarly to Moraes, Humchitt speaks to the barriers that are present with Indigenous communities switching from diesel to clean energy. Humchitt also speaks to the lack of funding that is available from the federal and provincial governments. She says even though the federal government recently invested $300 million dollars for Indigenous-led clean energy projects, $70 million went to setting up a government-led administrative arm and the rest gets split up between the more than 600 First Nations across Canada, and won’t result in much investment to each nation.

Despite the multiple barriers, Humchitt and the Heiltsuk Nation are implementing many aspects of their clean energy plan and have completed retrofitting in over 90 per cent of the homes in the community with renewable energy and heat pumps. They have also conducted energy audits on 200 homes and solar feasibility studies for both residential and commercial spaces, and are currently taking part in a renewable diesel pilot project.

Humchitt says that implementing the clean energy plan is to ensure that her nation is building “a better future for the little ones and the little ones to come.”

Moraes and Humchitt are leading some important work on behalf of their nations and there are many other First Nations that are leading similar and equally important work to move away from reliance on outdated diesel generation. If the government and utility companies made a meaningful commitment of resources to the leadership that remote Indigenous communities are showing regarding clean energy projects, our province and country would be moving in the right direction to reduce our collective carbon footprint, to align with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to realize Truth and Reconciliation.

Indigenous Nations know how to preserve and live in harmony with their lands – we’ve been doing it for thousands of years. British Columbia and Canada will only reach their full potential when Indigenous Peoples are able to step into theirs. Now is the time.

Chastity Davis-Alphonse, Tla’amin & Tsilhqot’in Nations, is an award-winning Indigenous relations strategic adviser and the edited of Mákook pi Sélim.

This article was first published in the June 2023 edition of Mákook pi Sélim – an Indigenous business magazine that exclusively features Indigenous and First Nations writers and journalists.