We understand the desire to follow a long-term decarbonization path but question the merits of the timeline, write the column’s authors

Since writing two columns discussing the NDP government’s modelling of the economic implications of its CleanBC Roadmap to 2030 (CleanBC), we have heard from advocates of the plan suggesting our description of the results is incomplete or somehow takes the projections out of context.

The latest pushback comes from Dr. Nancy Olewiler in an opinion piece published by BIV. We are pleased to engage with Dr. Olewiler.

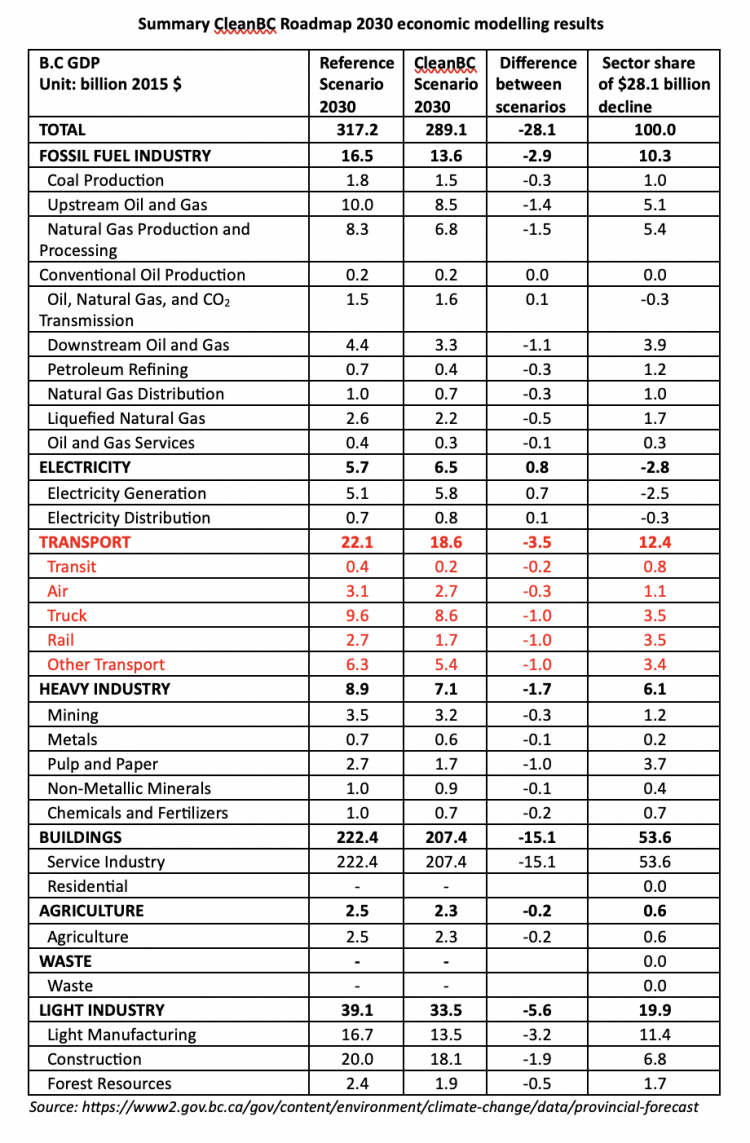

From the time we first stumbled upon the modelling results in an Excel spreadsheet posted in an obscure location on the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change’s website, our chief concern has been that the economic dimensions of CleanBC have never been adequately communicated to legislators, local governments, First Nations, businesses or the public generally. The modelling work shows B.C.’s economic growth slows to an annual pace of just 0.4 per cent in the second half of this decade and that the economy will be $28.1 billion smaller in 2030 (by which time the carbon tax rises to $170 per tonne and the array of other regulatory interventions are implemented).

The resulting setback in prosperity and job opportunities is concerning. From our perspective, anything that brings more attention to the economic impacts of CleanBC is welcome. Indeed, we would be relieved to learn of compelling reasons to ignore or even downplay the comprehensive economic modelling work the government commissioned. Alas, we have seen nothing that provides any such comfort.

Dr. Olewiler suggests we “fail[ed] to account for the benefits that await a British Columbia that embraces the inevitable energy transition.” In support of this claim, she cites an unrelated study published by Clean Energy Canada that projects “clean energy jobs in B.C. increase from 83,100 in 2025 to 400,800 by 2050 under a net-zero scenario.” We agree the energy transition that is already under way will continue. And, considering the generous definition of clean energy jobs used in the study, it is possible that the clean energy job count could rise by as much as 310,000 between 2025 and 2050.

But Dr. Olewiler’s shift to counting jobs in 2050 is misleading, not least because of the compounding growth effect. As detailed in a table on page 18 of the study she cites, the projected rise in clean energy jobs is based on a six-per-cent annual growth rate. This means between 2025 (the base year in the study) and 2030, B.C. can expect clean energy jobs to rise by 30,400. Between 2030 and 2040, the count climbs another 98,400. And because of compounding, most of the new clean energy jobs (183,000) materialize between 2040 and 2050. In other words, more than 90 per cent of the projected clean energy jobs miraculously emerge after 2030. While positive, these jobs will be of little benefit to workers displaced from existing jobs by CleanBC, or for the young generation facing diminished opportunities to secure well-paying jobs over the next six-to-seven years. Meanwhile, an economy that is $28.1 billion smaller in 2030 when the suite of CleanBC policies are in effect aligns with something like 100,000 total fewer jobs in the province by the end of this decade.

It is also helpful to understand how clean energy jobs are defined and counted in the Clean Energy Canada study. For example, most of these jobs (57 per cent) will be in the transportation segment – one part of the broader clean energy economy. Large numbers of the projected rise in “clean energy transportation jobs” arise when workers transition from manufacturing, selling, working on, and driving gas-and diesel-powered vehicles to manufacturing, selling, servicing and driving electric vehicles. Clean-energy workers shifting from today’s vehicle manufacturing and service industries to those based on clean energy does not equate to any net job creation. This is an important difference. The large number of additional clean energy jobs in 2050 that Dr. Olewiler cites is in fact an aggregate count that takes no account of job losses in the traditional energy and transportation sectors.

Pursuing a lower-carbon future will undoubtedly create new jobs and open additional economic development opportunities. But recognizing what drives innovation and the demand for clean energy products and services is important. Contrary to what Dr. Olewiler implies, there is little reason to believe that the details of B.C.’s climate policies are what matter for the local clean energy and critical minerals sectors to grow; global demand is the key. The U.S., which has no national carbon pricing policy, is outperforming Canada on a per capita basis in attracting clean energy and clean tech investment. The clean energy sector is booming in Texas, even though the state is governed by people who mostly reject the idea of human-caused global warming. Moreover, the clean energy economy represents only a small slice of the B.C.’s total GDP – about three per cent as of 2021, of which electricity generation (dominated by BC Hydro) accounts for one-third and waste management services for another half of one percent. Even if the clean energy and clean tech sector posts years of robust growth, the resulting economic lift will do little to offset the negative projected impacts for the rest of the economy under CleanBC.

Turning to the government’s GDP modelling results, Dr. Olewiler suggests “BCBC’s interpretation takes the CleanBC plan’s modelling assumptions out of context.” She goes on to write:

“the council neglects to note that more than 60 per cent of the $28 billion inferred lower level of GDP can be attributed to one simplistic assumption taken from a placeholder transportation policy (for the eventual clean transportation action plan). This placeholder in the model capped vehicle kilometers travelled in B.C. as a proxy representation of what a future, less gas-car-dependent province could look like.”

We have scrutinized all publicly available material released by the province and are unable to identify any reference to a “placeholder assumption” and its supposed role to explaining away 60 per cent the projected $28.1 reduction in GDP by 2030. A review of the table below summarizing the modelling results confirms that all sectors of the economy, apart from electricity generation and distribution, are smaller in 2030 under in the CleanBC scenario compared to the reference scenario (the latter includes a $30 per tonne carbon tax and other climate-related policies implemented or announced as of July 2017). We do not understand how any “placeholder” transportation assumption could account for “more than 60 per cent” of the $28.1 billion difference between the two scenarios, considering the entire transportation sector is responsible for only 12.4 per cent of the estimated reduction in GDP across the entire B.C. economy.

At the outset of her column, Dr. Olewiler states “[a]nd now, the Business Council of B.C. (BCBC) has opined on the costs of climate policy.” We recognize our columns are opinion pieces, but in this instance, feel compelled to note that both columns contained very little opinion and instead focused on reporting the government’s own economic modelling results. We did apply a few basic spreadsheet calculations to determine per capita incomes (GDP) and provide a framework for understanding the implications of the CleanBC plan on prosperity over the balance of the decade.

To the extent we did offer opinions, it was to convey our serious concern about how CleanBC is expected to impinge on B.C.’s future prosperity. We understand the government’s desire to follow a long-term decarbonization path, but we question the merits of advancing politically manufactured timelines and aggressive near-term emission reduction targets given the large economic costs of doing so. From where we sit, with the government’s own modelling suggesting the CleanBC Roadmap to 2030 will produce diminished opportunities for young people and set prosperity back more than a decade, the plan should be revisited.

Jock Finlayson is chief economist of the Independent Contractors and Businesses Association. Ken Peacock is the Business Council of British Columbia’s senior vice-president and chief economist.