Anyone living in an older apartment or condominium in Metro Vancouver could face a regional government fine for their building’s carbon emissions after 2028, should their strata not meet newly proposed guidelines.

On Thursday, the Metro Vancouver Climate Action Committee endorsed a regulatory proposal to track and penalize existing large buildings to the tune of $350 for every tonne of carbon pollution a building produces above a pre-determined emissions limit. The plan will apply to residential and commercial buildings that utilize natural gas and have 25,000 square feet (2,322 square metres) or more of floor space.

Metro planning staff will now initiate a second round of consultation, largely with owners and operators of buildings, but also community housing providers, industry and tradespeople, among others. It’s the last step before Metro plans to roll out the program in the mid-2020s.

While the proposal was endorsed unanimously, committee members such as Coquitlam councillor Dennis Marsden and Langley councillor Misty vanPopta expressed concern with how costs may be unfairly downloaded on strata tenants, who tend to have lower incomes and are seniors.

“I think it’s really important these costs don’t get downloaded,” said vanPopta.

But putting a price on excess carbon emissions in the building sector is intended to incentivize owners “to take advantage of supports” and reduce building emissions before the limits and fees take effect, planners noted in their proposal.

Heather McNell, Metro Vancouver’s deputy CAO of policy and planning, said the policy will simply spur stratas to undertake energy efficient upgrades as they are needed.

McNell said Metro Vancouver’s affordable housing units are undergoing the same process to reach a 45 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030, and at no added cost to tenants.

“If you’re doing good asset management… it doesn’t have to be downloaded onto our tenants; it’s just part of ongoing business,” said McNell.

So far the plan has only set emission limits for commercial buildings, not residential ones.

The plan is expected to help Metro Vancouver reach its target of reducing the region’s building emissions 35 per cent below 2010 levels by 2030, and by 2050, dropping building emissions to zero.

The plan is a beefed-up version of the City of Vancouver’s carbon emission reduction requirements for existing office and retail buildings over 100,000 square feet of floor space.

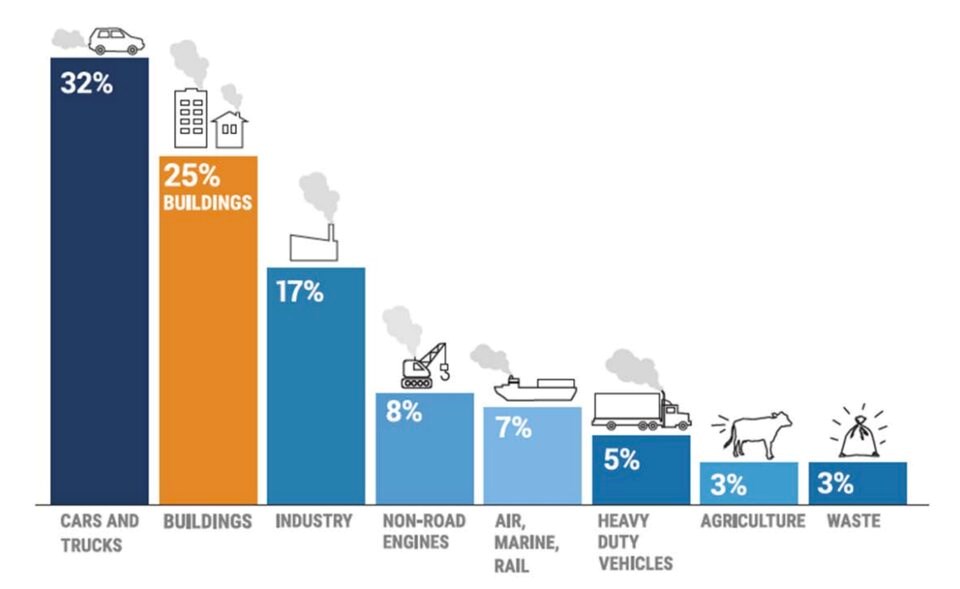

Big buildings produce 35% of Metro’s emissions

New buildings in B.C. must adhere to a number energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emission standards. But there are currently no requirements for existing buildings across the region to limit emissions from burning natural gas for heating and hot water, says Metro Vancouver, which counts 21 members and 2.6 million residents.

“Buildings last a long time, and decisions made today will impact building GHG emissions for decades,” warn staff in their report to the Climate Action Committee.

The proposed measures aim to fill that gap by targeting the biggest buildings first. Those include: low-rise or three-storey buildings above 25,000 square feet, mid-rise or five-storey buildings above 50,000 square feet, and highrise towers or retail and office complexes over 100,000 square feet.

Together, they account for less than two per cent of the region’s building stock — 9,000 out of roughly 450,000 buildings — but produce 35 per cent of the sector’s emissions, according to Metro.

Jordan Fisher, the chief decarbonization officer at the building consulting firm Fresco, says there is already enough technology to make big emission reductions in big buildings — whether through installing heat pumps, mixed heating systems or improving a building's envelope.

Fisher says he is already working with more than 200 groups — including Metro Vancouver, utilities like BC Hydro, the City of Vancouver and BC Housing — to drop carbon pollution in buildings.

“We have to be honest with ourselves that this is going to be challenging,” Fisher said. “It is really challenging, but we shouldn't let that challenge dissuade us from moving forward and actually doing it.”

The proposal comes at a time when building emissions in Metro Vancouver are on the rise, having climbed almost 10 per cent since 2010. Today, the burning of fossil natural gas for space heating and hot water account for about a quarter of the region’s greenhouse gas emissions, Metro says.

Residents of many smaller multi-unit buildings face stiff barriers when it comes to financing green retrofits, especially when electric upgrades are required. With few incentives, the residents of one building in Vancouver's West End recently faced a roughly $1.2-million bill when they attempted to swap out old gas furnaces and boilers for heat pumps.

But according to a preliminary analysis, Metro staff say that if the regional body were to quickly enact comprehensive regulation for existing large buildings, it could reduce the sector’s emissions six per cent by 2030 and 21 per cent by mid-century.

'Crucial' to protecting people from extreme heat

Beyond addressing climate change, Metro staff and health experts say the proposed regulations would improve regional air quality, make life more comfortable, and protect residents from extreme weather events made worse by climate change.

In a letter to the regional body, Vancouver Coastal Health medical health officer Michael Schwandt backed the plan to get more aggressive with building emissions.

There is evidence that poor ventilation and the continued combustion of methane gas for heating and cooking “can exacerbate or even cause childhood asthma,” Schwandt told Glacier Media. But one of the biggest health concerns associated with older buildings is managing heat, and deep retrofits could make a big difference.

“It’s crucial,” Schwandt said. “We know a lot of the buildings developed in the late 20th century are just not resilient to the high temperatures we’re expecting to see in the changing climate.”

In 2021, a record heat wave killed 619 people in B.C., many of them older individuals living in unventilated apartments.

Today, Schwandt said the province is much better prepared if another powerful heat wave were to hit the province. But public health bodies are still concerned many people are prevented from cooling their homes due to building regulations or strata rules.

“We still have some distance to go,” Schwandt said.

Emissions from gas stoves, district energy won't be charged

The administrative and carbon pricing fees would start in 2028 and only apply to a building’s emissions limit.

Initial emission intensity limits are 25 kilograms of carbon pollution per square metre for office buildings and 14 kg per square metre for retail buildings. Carbon pollution limits on other building classes are expected to be released through 2024 as staff carry out further analysis and receive input from engagement.

The proposal also requires each large building pay a $500 annual administrative fee that would go toward managing a program that would track the emissions and energy efficiency of every building.

Those reporting requirements would be phased in over three years, starting in 2026 with the largest buildings, and applying to smaller buildings over time, the proposal says.

A building's greenhouse gas limits would exclude emissions from cooking, “which are minor compared to space and water heating,” as well as those from district energy systems, according to staff.

Buildings that face “exceptional circumstances” are expected to be offered “alternative compliance pathways” that could include different timelines or emission limits.

At first, annual emission fees would also not apply to Renewable Natural Gas (RNG), a methane fuel that at the molecular level is indistinguishable from fossil gas, but is captured from wastewater treatment plants, landfills, wood waste or manure from farm animals.