“We’re here,” proclaims a framed poster on the wall in a cramped boardroom at the University of British Columbia’s regional office in Hong Kong.

The poster shows a Chinese junk sailing at sunset in front of gleaming buildings and bathed in maroon light.

“This picture has been at our office since we opened,” said the office’s executive director, Winty Cheung, who arrived soon after the university opened its Asian regional office in 2005.

Originally the office had a slightly larger footprint and was in a pricey district in central Hong Kong Island. Its move west, to premises with about 700 square feet of usable space in a grittier neighbourhood on the island, was largely to reduce costs.

“We are thinking of moving again so that’s why we haven’t spent much money renovating the place,” Cheung said as she showed a visitor the space.

The office itself is a couple of blocks inland from the ferry terminal to Macau, but all that is visible from the 12th-storey office is a jumble of older office towers.

Four co-op students work at desks in the cramped entryway to the office while five others, including Cheung, have other workspaces.

Despite its makeshift appearance, the office has been a success.

It is one of two regional offices that the University of British Columbia (UBC) opened to encourage international recruitment as well as to help recent UBC graduates find practicum placements and to facilitate fundraising from alumni who attend and network at events.

UBC’s other regional office is three years old and based in New Delhi, India.

(Image: Framed poster dons the wall of the small boardroom at UBC's Hong Kong office | Glen Korstrom)

The university’s enrolment figures suggest that money invested in the offices has been well spent.

International student enrolment from areas where the university has regional offices has soared, and that is expected to continue thanks to the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president.

One of the hallmarks of the Trump administration has been its anti-immigration stance, manifested in attempts to ban travel to the U.S. by nationals of six Middle Eastern countries.

His election win prompted UBC president Santa Ono to tweet the next day that a web page for a single graduate program at UBC received more than 30,000 hits between midnight and 3 a.m. Pacific time following the U.S. election.

The American Council on Education warned the U.S. government in an open letter earlier this year that Trump’s policies are having a “chilling effect” on U.S. universities’ ability to recruit international students.

“Anecdotally, what we’re hearing is that there has been an increase in interest in Canadian universities [because of Trump’s win],” said Karen McBride, CEO of the Canadian Bureau for International Education.

“Once the fresh data comes out, we’ll see the extent to which this has in fact materialized, but everything I’m hearing is that applications are up across the country.”

McBride pointed to a survey her organization conducted last year that found that 75% of international students who chose to study in Canada did so because they perceived Canadian society to be tolerant and non-discriminatory.

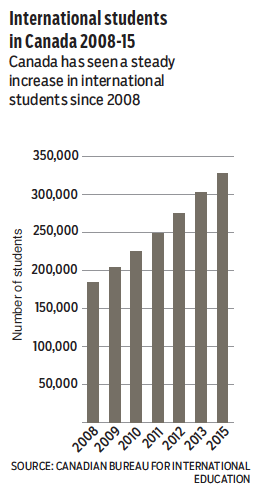

If a surge in international-student enrolment is borne out in the data, it would be an acceleration of a trend that has been observed across the country since at least 2008.

Growing enrolment

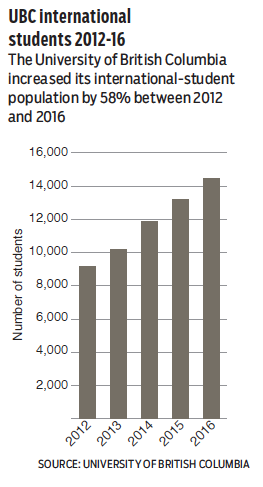

UBC has more international students than any other B.C. institution. Between 2012 and 2016, international enrolment at the school soared by 58%, jumping to 14,433 from 9,144 students.

Enrolment from areas where there are regional offices soared more significantly.

Students from mainland China and Hong Kong represent about 36% of UBC’s international enrolment, and their number rose by 63% between 2012 and 2016.

International students from India surged an even more impressive 140% during those same five years.

“In terms of creating awareness and raising the brand of the institution, for sure, the regional offices have helped raise exposure for UBC,” said Adel El Zaim, executive director of the university’s international office program and head of its international strategy.

El Zaim, who is based at UBC’s main campus in Vancouver, explained that the university launched its Hong Kong office because the school’s administration at the time wanted UBC to have a greater presence in the area.

“The main idea was to open offices in places considered strategic for UBC,” El Zaim said.

“The Hong Kong office covers all of the Asia-Pacific region. It is not just for Hong Kong or the Chinese mainland.”

Other B.C. universities do not have international offices in Hong Kong or China and have not seen the same surge in international-student enrolment from those areas.

Simon Fraser University (SFU), for example, has chosen to pursue international enrolment in China through co-op programs and university partnerships, SFU vice-provost Tim Rahilly told Business in Vancouver.

“For the purposes of student recruitment alone the cost of opening a regional office would likely not make sense,” Rahilly said. “Our recruitment is seasonal and involves a number of different destinations in the region.”

Although SFU’s recruitment in China and the Hong Kong region has seen far less growth than has UBC, those regions combined represent a much larger concentration of SFU’s overall international student count.

(Image: Adel El Zaim oversees international strategy for UBC along with the university’s regional offices in Hong Kong and New Delhi | Chung Chow)

Almost 54% of SFU’s 5,976 international students in 2016 were from China and Hong Kong. Enrolment from those regions, however, has risen only 4.3% since 2012, and enrolment from Hong Kong alone fell slightly between 2012 and 2016.

“We would love to have students from all over the world but we recognize we cannot be present in every country or city, and have to prioritize our efforts,” Rahilly said.

At Capilano University, enrolment from the Asia-Pacific region has fallen more than 10% in the last five years. Donna Hooker, director of the university’s Centre for International Experience, said this was because her university ended recruitment-oriented partnerships in the region.

“We chose not to renew [the partnerships] because they were not consistent with the long-term direction of the university any longer,” she said. “They were arrangements that were in place when we were a college.”

India, however, has been a focus for Capilano University recruitment, and international student enrolment from southern Asia has risen more than sevenfold to 367 between the 2012-13 and the 2016-17 school years, Hooker said.

The university embarked on a partnership in 2014 with marketing and communications company M Square Media, which represents the school in various cities on the subcontinent.

“It’s a contract,” she told BIV. “They represent us and we describe the arrangement as a subcontinent office.”

This story is part of a larger feature on post-secondary recruitment in the era of U.S. President Donald Trump. For the next segment, on CIBT Education Group readying for a surge in ESL students, click here. •