The increasing cost of providing health-care services is an issue of growing significance for governments, businesses and the public.

Health expenditure data published by the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) shows that over the past three decades provincial government health spending in B.C. has grown faster than many other dimensions of our society and economy.

For example, B.C.'s spending on health care has increased at an average rate of 7.5% per year – much faster than the annual increase in the province's population (1.7%), the higher-health-care-cost 65-plus population (2.9%), the economy as a whole (5.3% annual growth in GDP), general price inflation (3.4%) and total provincial government spending (5.2%).

In light of these increases, we have seen a renewed focus on long-term health-care funding. This has led to conversations between provincial and territorial leaders about funding past 2014, culminating in Canada's finance minister announcing that after 2017 the formula for annual health-care transfers would be simplified, linking federal-provincial transfer payments to annual increases in provincial nominal GDP. With these conversations being driven by increasing costs Canada-wide, it is useful to consider what the drivers to increasing health-care costs in B.C. have been, and, given these drivers, what we might expect in the coming years.

Looking back over the past three decades of CIHI data for the long-term trends and the past decade for more recent trends, general price increases (i.e., inflation) accounted for 20% of the increase in health spending over the past three decades and 23% of the increase over the past decade.

Population growth, on the other hand, accounted for a much smaller share of spending increases over the same two periods (8% and 14%, respectively). The impact of B.C.'s changing age composition – the "aging population" effect – accounted for 15% of the long-term and 24% of the more recent increases.

Combined, these three factors – considered to be the primary drivers to health-care spending – have accounted for 43% of the increase in provincial government health spending in B.C. since 1979 and 61% since 1999.

Said differently, a significant proportion of historical spending increases (57% over three decades and 39% over the past decade) can be attributed to non-primary factors. These secondary drivers include inflation specific to the health-care sector that was in excess of general price inflation, an increased propensity for B.C.'s residents of all ages to use the health-care system more and an increase in the quality of health-care services provided.

While a seemingly simple taxonomy, this classification is crucial, because we have more control over the secondary drivers than the primary ones. We cannot put a cap on population growth, stop people from having birthdays or halt the general rise in consumer prices; however, we can affect both delivery (cost increases that are specific to the health-care system) and use (the increasing per-capita consumption of health-care goods and services).

So what's in store for B.C. over the coming three decades?

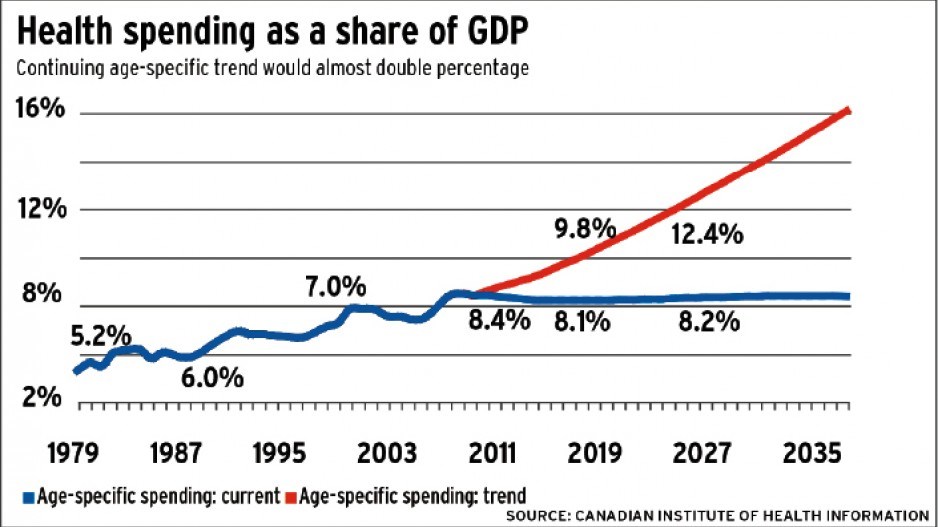

If we consider projections of B.C.'s population by age and hold the current age-specific per-capita spending pattern constant, the outlook is not as bleak as media headlines would have you believe.

With a relatively modest outlook for economic growth (2% per annum), total provincial government health spending as a share of the economy would remain relatively constant at today's levels (about 8.3% of B.C.'s real GDP) out to 2041. Even in the face of all of the boomers having passed their 65th birthdays over this period, B.C.'s health-care spending as a share of GDP would not explode.

In considering the history of increasing real age- specific spending, however, a more dismal pattern emerges. Allowing the increases in age-specific per-capita spending seen over the past decade to continue would result in health spending almost doubling as a share of the province's economy, reaching 16% of real GDP by 2041. Simply put, B.C.'s health-care system, under this scenario, would be unsustainable.

Just as businesses and residents must rationalize their finances, we need a financial plan for B.C.'s health-care system that requires a match between spending and our ability to pay for it. With no such plan, health expenditures will continue to grow faster than the economy, thereby crowding-out spending in other areas and/or resulting in a greater personal and business tax burden.

The statistics clearly show that, in considering the drivers to health costs, we need to stop blaming the seniors and look to everyone in the hospital waiting room (including the doctors and nurses). We should also be looking to these same people for innovative solutions to what could be a growing challenge for B.C.'s economy. •