To make housing affordable in Canada, 3.5 million more units need to be built by 2030, according to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. B.C. alone has a projected supply gap of 610,000 homes.

In response, all levels of government are putting forward a dizzying array of policies aimed at stimulating new development. However, some of these policies will have the unintended consequence of demolishing tens of thousands of good quality homes. The sad irony in our linear economy is that building new means tearing down the old.

Among these initiatives is the B.C. government’s ‘Homes For People’ program, a new province-wide housing plan to encourage the construction of small-scale multi-family homes through municipal zoning changes. Under the program, municipalities larger than 5,000 people will be required to simplify their zoning bylaws to encourage development of multiplexes on lands traditionally zoned for single-family homes.

These amendments will allow for three to four units on lots currently zoned for single-family or duplex use, depending on lot size, and six units on larger lots close to transit stops with frequent service. In taking these steps, the province is mirroring amendments recently passed by the City of Vancouver to its zoning policy and upzoning initiatives in other jurisdictions across Canada.

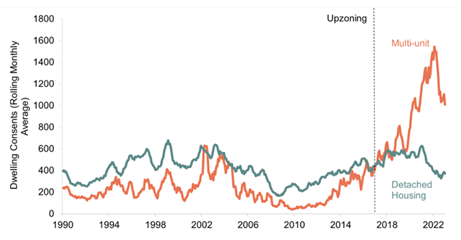

The province’s own analysis suggests that we could see more than 130,000 new small-scale multi-unit homes built in B.C. over the next ten years thanks to this policy. The experience in other jurisdictions bears this out. New Zealand’s City of Auckland upzoned three-quarters of its residential land area in 2016 by abolishing single-family zoning, resulting in more than 20,000 multi-family homes being constructed in five years.

What’s missing from B.C.’s densification plan is what the province plans to do to with the homes removed to make way for multi-unit developments. Aukland’s plan resulted in more than 7,000 additional demolitions to make way for denser housing.

Every year over the past decade, an average of 3,207 homes were demolished in Metro Vancouver. That equates to 8.8 homes destroyed every day, many in good to excellent condition. Across Canada, it is conservatively estimated that 30,000 homes are demolished each year.

The B.C. government’s relaxation of zoning restrictions on single-family lots will only increase the collateral damage associated with this Grand Demolition. The actual number of homes demolished as a result of this policy is difficult to predict. But if we track Auckland’s experience, B.C. could see upwards of 41,000 single-family homes demolished over the next five years.

House-moving experts, Nickel Bros, estimate that 20 per cent of these homes could be relocated and retrofitted to provide quality housing.

Around a quarter of all material dumped in landfills in Canada comes from building demolition. In B.C., the figure is even higher: 40 per cent of all waste in the region comes from construction, renovation and demolition activity.

Several B.C. municipalities, including Victoria, Burnaby and the District of North Vancouver, have enacted deconstruction bylaws, but they are of varying scope and effectiveness. The reality is that under current policy, most homes in B.C. continue to be demolished and sent to landfill.

Demolition runs contrary to public policy objectives targeting affordable housing, climate mitigation and solid waste reduction and is completely absent from discussions on housing policy at all levels of government.

Our linear economic paradigm continues to be blind to the opportunity of relocating and repurposing these homes to provide housing in other communities. It doesn’t need to be this way. We could save existing homes and have them contribute to the housing solution while significantly reducing construction and demolition waste and associated greenhouse gas emissions.

Capturing and saving these homes is a huge economic opportunity for the province. Retaining and relocating existing homes can generate high-skilled jobs in the home relocation and renovation industries, as well as realizing the value in existing homes and high-value building materials, such as old growth timbers, currently treated as waste.

Following recommendations in Light House’s Blueprint for Change report, any home slated for removal should undergo an assessment to determine whether it is a candidate for relocation or deconstruction. Only if neither option is viable should the home be demolished.

Local businesses are already filling the gap. Renewal Home Development has developed a Home Relocation and Repurposing Program that takes high-quality homes slated for demolition, moves them to a centralized facility where they are renovated with energy efficiency upgrades and other improvements, and relocated to coastal First Nations communities and rural non-profit housing associations. For homes that can’t be relocated, companies like VEMA Deconstruction have developed innovative processes that make deconstruction a faster and less expensive option to demolition.

With a growing population in Canada, densification is necessary and inevitable. The question is whether we will develop policy to support sustainable densification, or whether we’ll end up seeing tens of thousands of good quality homes ending up in landfills. While we zone up, let’s seize the opportunity to relocate or deconstruct homes to both support the creation of affordable housing and environmental sustainability.

Gil Yaron is managing director of circular innovation at Light House, a Vancouver firm dedicated to helping government and industry advance regenerative built environments.

Updated Feb. 16 to clarify data from the first paragraph can be attributed to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation.