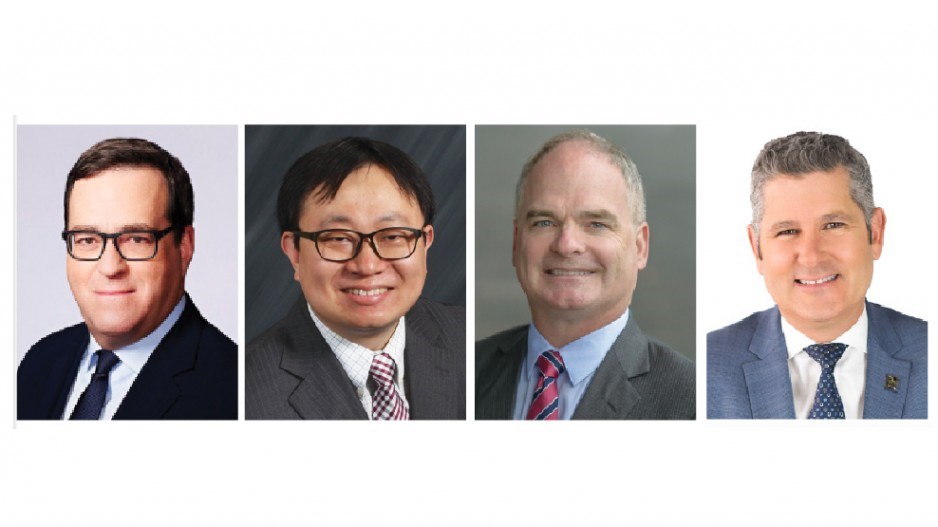

As part of BIV’s continuing coverage of the struggle to get B.C.’s economy back on track as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes, BIV reporters Glen Korstrom, Tyler Orton, Albert Van Santvoort and Hayley Woodin asked four of the province’s leading economic experts – Pierre Cléroux, chief economist for the Business Development Bank of Canada; Chulwoo Hong, senior economist with IHS Markit; Ken Peacock, chief economist with the Business Council of British Columbia; and Martin Thibodeau, regional president, British Columbia, of RBC Royal Bank – to share their perspectives on the province’s immediate and long-term prospects for recovery. Their answers have been edited for space.

Will the province’s rising minimum wage have much of an effect on employers hiring back workers and lowering the unemployment rate?

Pierre Cléroux: The level of job creation is going to really depend on demand. If you’re busy, if you have demand for your products or services, then that’s [minimum wage] not going to be the most important factor. Minimum wage, the fact that it’s increasing, I don’t think it’s going to have a huge impact on rehiring people or not. What I believe is the initial recovery is going to be quite rapid.… But it’s going to take some time before we go back to the pre-crisis level.

Chulwoo Hong: Overall, I don’t expect there will be a big impact. In the short term, the increase of the minimum wage will be an extra cost pressure to employers who may have already significantly suffered from the pandemic. In the reopening phase of the economy, the impact will be very minor as companies have to respond to the increase in demand after the pandemic.

Ken Peacock: I was on the fair wage commission involved in setting out the time frame for the minimum wage increase, which at the time seemed reasonable, but, of course, those were different times. There is no question that the minimum wage will add costs and the businesses that have the highest concentration of minimum wage employees are also those most hit by COVID-19, like food services, retail. So there’s no question there’s additional costs, but the flip side is that there’s a lot of families hurting right now that would benefit from higher wages particularly at this time, especially if someone else in the household has lost their job. But the real concern is there is no getting around the reality that it does add costs to business operations at a time when thousands have had no revenue or very little for a couple months. They face closures, and they’re facing what’s going to turn out to be the deepest downturn in a century.

Martin Thibodeau: Unemployment is extremely high, but also, as we reopen the economy, these numbers are coming down very quickly. We saw the country at 13% unemployment, and B.C. in better shape than the rest of the country. These numbers will improve over the summer dramatically.

Many businesses were closed or shut down in a self-inflicted recession, if you will. A lot of jobs were lost. Numbers for unemployment for April and May were unprecedented.

There was job creation in May – a net positive. In the end, the level of unemployment will be higher than the 3.4% that we had before. Where exactly is it going to land – 5%, 7% or 8%?

During the summer you’ll see a lot of people coming back to work. We’ve already seen that. We’ll see more as we reopen and kids go back to school in September.

There will be some unemployment because there are some sectors that are more affected than others.

Which sectors of the B.C. economy do you see rebounding the fastest from the COVID-19 downturn? Which ones are likely to be laggards?

Cléroux: The numbers are showing, for example, manufacturing is coming back more quickly than other sectors. In general, employment in B.C. is down by 13% and manufacturing is down by only 3%.… Same thing for natural resources, which has almost [recovered] all the job losses during May. So some of the sectors are coming back more quickly than others.… Tourism [is] going to take a longer time to go back to the pre-crisis level because the border’s closed with the U.S.

Hong: It’s a little bit unclear. I expect that overall GDP will modestly rebound – we’re talking 3.5% in 2021 – after a 7.8% decline in 2020. Sectors hit the hardest will rebound relatively stronger in 2021. That includes the forestry and logging industry, wholesale and retail trade – those will rebound fastest in 2021 in terms of the gross rate. Meanwhile, manufacturing, agriculture and fishing and administrative and support services will be the slow-growth industries in 2021.

In terms of the recovery, I think we also need to [compare] the level of output recovered to 2019 levels. Output for most sectors in 2021 will not be able to recover the loss this year and will remain below 2019 output levels. I forecast that utilities, professional services and social assistance outputs will fully recover and rise above 2019 levels; however, output in mining, forestry and logging, accommodation services and wholesale trade will be significantly below pre-COVID-19 levels.

Peacock: That’s a relative question. We’re going to see a preliminary bump in some of the sectors hardest hit, and you’re already seeing preliminary signs of that. That’s largely a math issue. You shut down retail, and then you reopen it, a certain amount of employees are going to be called back to work and rehired and that results in a significant bump, but that’s just because they’ve fallen so far. So you’re going to see some recovery in the food sector space, retail and personal services. But the medium- and longer-term prospects are definitely more uncertain, particularly for the accommodation sector and the food services. Many restaurants, I’m hearing more and more, are finding it difficult, if not impossible, to operate on a 50% capacity model. International tourism, based on the reopening plan that the province has put out, is shuttered for the foreseeable feature. The whole retail model is shifting; consumers are moving online, there’s some tentativeness, I think, for people to go out in crowds still. So once we get past this initial bump, the medium-term prospects aren’t as good, and it’s a little more difficult to tease out sectors that will grow more quickly….

The sector that’s going to struggle the most is international travel and tourism; you can cite the border closure; almost every country in the world, except for a handful, have some type of international restriction on air travel. Those will probably be lifted in an uneven and disjointed manner, so that’s going to be the sector that’s particularly hard hit. The other one, of course, is the big sports venues, concerts and entertainment theaters…. On the upswing, sure, there are sectors that are emerging and probably will do well. I guess some of the more obvious candidates are the whole online retailing and selling sectors and the delivery services that are associated with that. Amazon’s [Nasdaq:AMZN] stock is up; they’re hiring more workers so those will be growth areas. Some technology companies will do well; technology and digital services companies do well. Tech and media companies are in a position to have people work remotely, and it seems to be functioning quite well. The big examples you can cite there is Facebook [Nasdaq:FB], who just told all their workers to stay home.

Thibodeau: I was just talking to my team in northern B.C., and that region never slowed down. There are big infrastructure projects – LNG being one of them.

All the infrastructure projects that we have in B.C. are contributing and will continue to be very, very helpful for our economy.

Manufacturing came back quickly. Many manufacturers pivoted and modified their chain of production to go from making a product that wasn’t needed to produce hand sanitizer.

We needed a lot of these products early on. There were also Plexiglas companies that were quick to adapt.

Real estate is 28% of the GDP of B.C., let’s say 30%. It was a great decision from the government not to close the [construction] market in our province.

We have a large market share of that business. It never stopped. We had a lot of one-on-one with clients during the pandemic. They have strong balance sheets. They are the big developers that we have in the city.

The challenge with real estate is immigration.

We used to have 60,000 new immigrants coming to B.C. each year. Now they’re not coming because our borders are closed.

Tourism and all of the service industry has been hurt. The B.C. economy is one-third service, and this crisis has hit the service industry. It will take a long time to rebound. The cruise ships aren’t coming. That’s one million visitors not coming between April and November. That will impact hotels, restaurants and small shops.

How much of a concern is inflation?

Cléroux: It’s not a big concern. Inflation was negative for the first time in April, and the reason why is because the price of gasoline has really [gone] down, and that’s the reason why price levels were negative.… To have inflation you need pressure on demand and this is not what we are going to see right now for at least a year or more. As consumers are going back, retail sales [are] going to increase … I’m not worried. For the next few years inflation is going to remain quite low in Canada and British Columbia.

Hong: At this moment, inflation is deemed not an imminent concern considering low oil prices and that the economy is performing under capacity, which is not giving upward pressure to inflation.

Peacock: I’m not worrying about inflation right now. Governments and central banks are injecting an inordinate amount of stimulus, both monetary and fiscal, we know that, but I don’t see a lot of inflation on the horizon. We’re looking at the biggest global downturn since the Depression. Falling prices might be more of a concern than rising. Two years from now, if all this stimulus remains in place and the global economy does manage to get some traction, it’s entirely possible that we could start to see some price increases and inflation being stoked a little bit. I think policymakers and governments are going to have to be alive to that potential and the risk, but for the time being the downturn is the concern, not runaway inflation.

Thibodeau: No, inflation is not a concern. Early on, we thought deflation could be in play. Rates came down three times very quickly. The Bank of Canada did a great job – central banks in general did a good job. We learned from the credit crisis the importance of early intervention to avoid what in this case could have been a depression and deflation.

Some products are more expensive, but there are some others that are offsetting that. For example, groceries cost a bit more, and gas and fuel are way less expensive. So there are lots of offsets. We don’t see, on the horizon, inflation to be an issue.

Interest rates are going to stay very low, close to 0%.

One thing we’re trying to avoid, and the Bank of Canada said it, as did economists in general, is negative interest rates. They haven’t shown to be effective to start an economy and maintain an economy, or keep an economy.

How is B.C. is managing the reopening of the economy compared with other provinces?

Cléroux: Our forecast says that the impact is going to be less in British Columbia than it is on average in Canada. And the growth next year in British Columbia is going to be solid. And part of the growth is going to come from the large industrial projects that British Columbia has. For example, the LNG Canada project, which is $40 billion over 10 years, was slowed down during the pandemic because they have to respect the rules, but now it’s coming back to full capacity.… In general, the B.C. economy is going to come back faster than the average in Canada.

Hong: It all depends on the state of affairs of the new COVID-19 cases each province is facing. However, I believe that the B.C. government understands that you have to have physical distancing to flatten the pandemic curve using B.C.’s modelling. They are cautiously opening the economy, which is the very tough part. I believe they fully understand the impact of the reopening phase as well, and the economic impact. I believe they are doing their best.

Peacock: Reading the plan, B.C. is in line with what’s going on in other provinces; the reopening is good. I think B.C. managed the crisis much better. We’ve had better outcomes, and some of that is attributable to how we’ve managed it compared to other provinces. We are global leading in terms of management and containment of the virus, so on that front, very, very good. It remains to be seen on the reopening just how B.C. will go. But I would say that we’re broadly in line with what’s going on in other provinces. And we were a little bit better in that we didn’t close down construction and some of the other sectors that other provinces did. So keeping construction operating is a big deal; it keeps a lot of people working and a lot of economic activity going. It appears that decision was the right decision; it was successful. We don’t have big case loads in the province. And we have some of the best results or outcomes in the world. So that turned out to be a good decision.

Thibodeau: We are doing a good job, but we have to make sure that we don’t do a step forward and two steps backwards. I’m very pleased at how Dr. Bonnie Henry has acted.

The four phases of the province’s plan are quite clear. They’re working. We have flattened the curve.

We know more about the virus, who it hits more and where. We can control it. We have a lot of measures and a lot of practices that she has put in place.

We’re not going overboard with restrictions, and so the B.C. economy is reopening step by step. I think it’s prudent, it’s responsible and it’s working.

We haven’t had to go back and forth, two steps forward and three steps backward. You try to avoid that as you try to restart the economy.

For RBC, on that front, we’ll have 92% of our branches reopened by the end of June.

What are the biggest challenges to the provincial economy in the short term and long term?

Cléroux: The economy is restarting now and is going to improve every month in the next year, but if we have a second wave this is really going to delay the recovery. So I think that’s the biggest concern [in the short term]. In the long run, the downturn was really quick, very sharp. It took only two months to create a lot of unemployment, but it’s going to take more time to recover totally.… Before we go back to the pre-crisis level, it’s going to take more than a year. Probably by the end of 2021 or even the beginning of 2022.

Hong: The biggest challenge to the provincial economy will be the pace of rehiring. The pace of job recovery will be an important indicator to B.C.’s economic recovery in the short term. I believe that the April job cut was the bottom of pandemic employment lows, as widely expected. B.C. lost close to 400,000 jobs throughout March and April. After April – which was the first full-month measure of the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak – employment modestly rose, adding only 43,000 jobs in May as the B.C. government gradually reopened the economy. However the unemployment rate still increased to 13.4%, which was the highest rate over 30 years.

I expect a slow employment recovery for the rest of the year, largely due to the limited operating capacity of businesses and businesses very cautious on expanding their hiring, given the high level of uncertainty. I forecast employment will decline 7.8% in 2020, with the unemployment rate averaging 8.6%.

Peacock: The short term is just reopening and getting people back to work and getting to enough spending and enough demand that people can get back to work. So for me, the No. 1, single biggest challenge is the high unemployment rate and getting people back to work. If some of these slower recovery sceneries unfold, which is appearing to be more and more likely, and we only get back half of the those lost jobs by the end of the year, we’ll still be down 200,000 to 150,000 jobs. Unemployment will still be very high, youth unemployment in particular is very high right now, almost 30%. [There is] potential of … long-term damage in the labour market from people being out of work for protracted periods of time. Business insolvency is right up there, and they’re of course related, when businesses go under and fail then people lose their jobs as well. So in the near term, a combination of lost jobs and business insolvencies … particularly when we get later in the year and some of the federal supports begin to wind down. The [biggest challenge in the] long term is just the recovery, getting B.C.’s big economic engines back up and going.

Thibodeau: In the short term, the challenge is to create demand. Just because businesses have reopened, it doesn’t mean that people will come back.

This is a severe crisis, and it’s one thing to say my store is open, but are people buying? We have an economy that is based a lot on consumer spending. That’s a big part of our growth. People will be more prudent in how they work, the way they shop, the way they watch, and learn.

Long term? That’s a good question. I find that there is so much upside long term for B.C., for reasons of our health care and education. It’s a safe place, and inclusive, although we’ve had hiccups. Future crises will come again, and digitizing our economy is probably for me, the biggest concern. We’re behind in relation to North America, Asia and Europe.

Those who have a plan to use digital and virtual technology have been able to weather the storm. Those who didn’t might disappear. So digitizing and helping our small businesses and medium-sized businesses to see the importance of having a digital platform is important.

We have close ties with the Americans but we are between the Americans and China. Tension between China and the U.S. is not good for B.C. because we have very little size in comparison.

We’re a small economy in the scheme of things so I see this one as a risk. A prolonged global recession is also a risk to the Canadian and B.C. economies. •