Collaboration between communities and all levels of government is key to managing the impacts of climate change as governments grapple with the costs of a warming world.

That was the message Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM) delegates heard on Sept. 16 at the annual conference in Vancouver. The UBCM convention, on from Sept. 16-20, sees local politicians gather to discuss a variety of topics: from the toxic overdose crisis to housing and homelessness.

That message was coupled with the idea that the impacts of climate change are increasing and putting pressure on already limited resources.

What they also heard was that Mother Nature herself cannot be forgotten in the mix, and that the services nature itself provides must be inventoried to help manage change and risk.

The community of Princeton is a town of 3,000 that sits in both forest fire and flooding zones. Mayor Spencer Coyne said the impacts, financial and otherwise, can be “astronomical.”

He stressed the need for collaboration with senior levels of government but expressed frustration after his town was denied federal mitigation funding of $554 million needed to protect his town.

“It’s just one thing after another,” he said. “The costs just keep adding up.”

He cautioned other elected officials to start planning now.

With his town built on a flood plain at the confluence of the Tulameen and Similkameen rivers, he said a flood could cost the city its central core.

“We will lose our downtown. We will lose our centre of commerce. We will lose our industry,” he said.

He said the town is now planning to move back from the river.

“One-third of the population will have to be moved," UBCM delegates heard.

On the forest front, Coyne said Princeton and neighbouring towns have been creating firebreaks between their towns to protect each community in the event of catastrophic blazes.

And, it’s not just senior government that communities need to partner with. It’s also industry and regional districts, he said.

More frustration with Ottawa

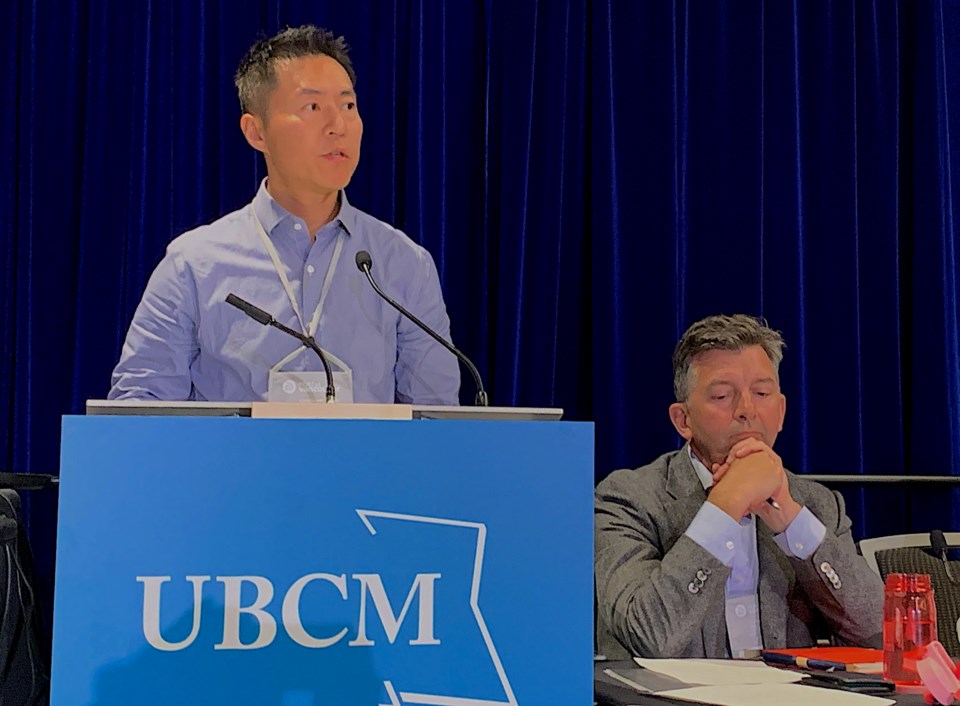

In Richmond, engineering planning manager Jason Ho said threats come from rising sea levels, flooding, freshets and increasing rainfall levels.

Delegates heard the city has 49 kilometres of dikes, pumping stations and water drainage pipes to handle the situation currently.

Ho said things continue to change and that means adapting, which involves raising dikes and land. That, he said, costs money and financial hits to the city for planning, construction and land acquisition.

That’s where Richmond’s frustration comes in — again with the federal government. Ho said getting project approvals through Ottawa can take up to 18 months.

What Richmond does have, Ho said, is a flood protection utility. With funds assessed against property and business, it has generated $23 million in funds, a number the city wants to increase to $30 million by 2032.

Further, Ho said the city wants to involve developers in creating "super dikes" to help protect the city’s land and residents.

Municipal insurance

B.C.’s municipalities do have protection from the impacts of climate change from the Municipal Insurance Association of BC (MIABC).

Samantha Boyce, the association’s in-house lawyer and manager of strategic innovation, said the the organization was created by the UBCM to provide a pool of insurance money for the 170 municipalities.

Boyce said the association identifies risks climate change presents and offers advice on risk management and mitigation.

She did not sugarcoat the fact that climate change impacts are going to get more difficult.

“It’s only going to get more expensive from here,” she said. “The increasing frequency and severity of climate events are having a significant impact.”

The MIABC operates differently than other insurance agencies. It is the municipalities' members, local politicians, who drive its board decisions.

Mother Nature

Roy Brooke, executive director of the Natural Assets Initiative, told delegates they must see nature as a service provider to their communities.

He said forests, wetlands, riparian and coastal areas, plus floodplains, all have a role to play in mitigating climate change.

“There’s a lot of very straightforward things that elected officials can do to protect natural assets, Brooke said.

For example, a wetland can recharge aquifers and purify water as well as provide recreational, social and spiritual services.

“There is no downside to understanding what natural assets you have in your community and what services they provide,” he said.

“But, once they’re gone, they gone,” he cautioned.

Brooke said at least two dozen local B.C. governments are now looking at natural asset management.

Among other resources, Brooke recommended the report ‘Getting Nature on the Balance Sheet.’ The paper calls for recognizing the financial value provided by natural assets and argues for a revamp of accounting rules so as to safeguard natural resilience.