Melissa Kwan started making trips to New York City in 2013 because she was mystified at how cautious and frugal Vancouver real estate marketing firms were when it came to spending money on new technology.

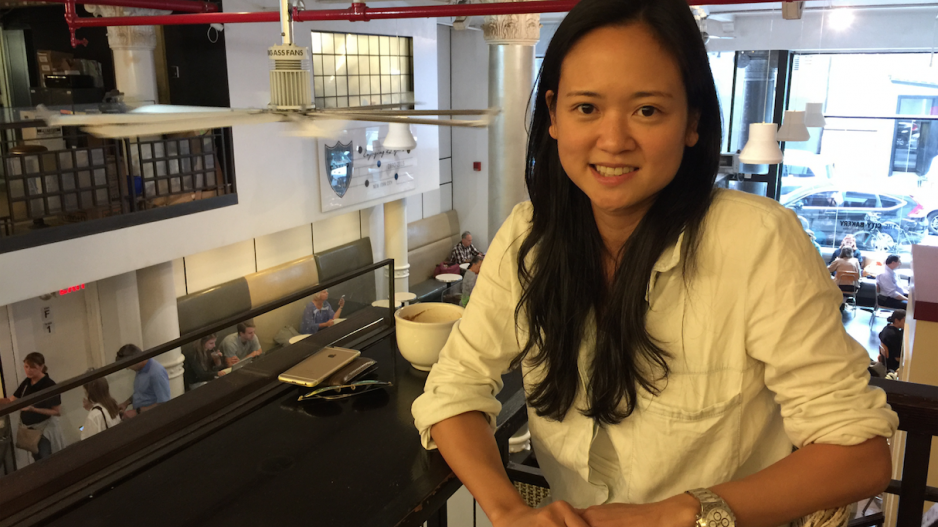

“The attitude among real estate marketers in Vancouver is protecting what you have,” Kwan told Business in Vancouver between sips of a caffè latte at one of her favourite Manhattan cafés, City Bakery on 18th Street.

The coffee house’s high ceiling allows for an upstairs loft, where patrons sit at counters and peer down to the bustle below.

Kwan knows the Vancouver real estate world well. In the mid-2000s, she worked for Aspac Developments and helped market Two Harbour Green.

Her company in 2013, Flat World Apps, had created software that brokers could use as a sales tool because it enabled potential buyers to see virtual floor plans of suites and buildings.

Consumers could tap smartphones for close-up views of suites they might buy and to get a better sense of the completed project’s appearance compared with the way it might look in a paper brochure.

Executives at Vancouver’s real estate marketing companies told her that they did not want to take a risk by adding an expense for their clients, she said. They feared losing that client to crosstown competition.

Marketers in New York, in contrast, are keen to be noticed, Kwan said.

They go big. They spend money to be seen as innovative and cutting-edge.

Kwan found a buyer for her product in the Indian real estate conglomerate DLF.

That contract helped finance month-long trips to the Big Apple that were interspersed with trips of about a month or so in Vancouver.

Were it not for the cheap accommodation she found on Airbnb, she doubts that her bank account could have sustained all the travel.

Hard work cold-calling companies in New York landed work for the Trump Organization’s residential marketing division and Citi Habitats.

Kwan took the plunge and moved to New York in 2015 with a new company, Spacio, and found clients such as Halstead, Brown Harris Stevens and Corcoran Group. Her software enables realtors to track visitors to open houses and understand how to better allocate marketing budgets.

Kwan’s business partner, Ting Sun, and four employees remain based in Vancouver.

“The only reason we’re even close to being profitable is because our team is based in Vancouver,” the 34-year-old told BIV as she peered down to the first floor of the café, where cashiers in white baker hats were serving customers.

“It would not be a sustainable venture if we had to hire in New York City. We would probably have to pay 100% to 150% more in salary for each person,” she said.

Indeed, living in Manhattan is notoriously expensive with real estate costs that often tower above Vancouver, despite a recent Century 21 study that showed that condo prices per square foot in Vancouver have surpassed those in New York.

Unsettling realities of getting settled in the Big Apple

Discussions about how to afford the steep Manhattan living costs are a favourite pastime among ex-pat Vancouverites and those currently making extended visits to New York.

Even those who have achieved tremendous success sometimes can’t help talking about how they used to make long treks on foot because they couldn’t afford the subway.

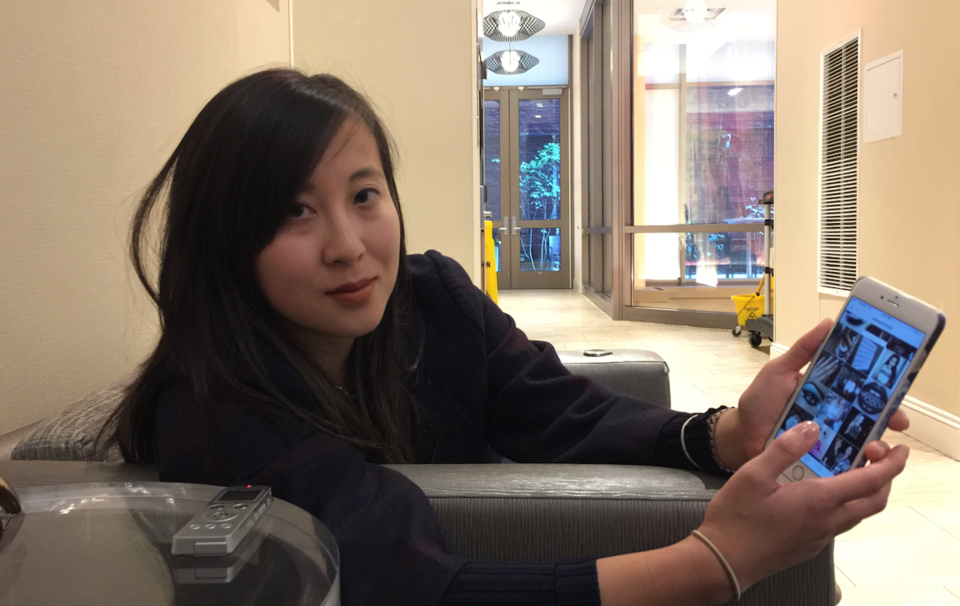

MuseFind CEO Jennifer Yemu Li Chiang told BIV that she never knew what hotel she would be staying in from day to day.

Each day, she would check out of her hotel and go to work. Then she would try to snag a discounted deal later in the evening. Other times, Chiang, who is now 29, said she would shower in a gym that was in her office building.

She would stay late enough to be the last to leave but instead of heading out, she would sleep on a futon in the office’s games room. Chiang then had to get up early to erase any trace that she had slept at the office.

(Image: Musefind CEO Jennifer Yemu Li Chiang is interviewed by BIV in the lobby of the Homewood Suites by Hilton hotel in midtown Manhattan | Glen Korstrom)

Another former Vancouverite, Nicole Williams, recalls a similar existence.

“I was living on someone’s couch – a friend’s trundle bed,” said Williams, who graduated from the University of British Columbia and lived in Vancouver for many years before she left the West Coast at age 34 in 2004.

Williams’ Nicole Williams Works is a media company that started with her writing what she describes as “edgy” books for Penguin Group about how to act as a woman in the business world.

Through the years, she created TV shows for Oxygen Media, was a spokeswoman for LinkedIn and has been a regular guest who discusses career issues on the Today show.

“The first two years after coming to New York, basically, I was so poor it wasn’t even funny,” Williams told BIV during a lunch at the Mexican restaurant Dos Caminos, at the corner of Broadway and 47th Street at Times Square.

Williams got her first break in Vancouver when local production house Force Four Entertainment produced her first TV show, Making It Big. When that show was sold to a U.S. network there was a glitzy gala that Williams remembers well.

Guests all got into cars to go home after the event. Williams remembers not even having enough money for a bus, so she had to walk home across a darkened Central Park.

“I thank God for that experience of no money in New York because it helped me learn how to be industrious,” she said.

“When I ended up getting funding, I understood what money was, what I could use it for and how to leverage it. It informed how I ran my business, which was really lean.”

The good news for impoverished newcomers is that New Yorkers are very helpful by nature, according to both Williams and Kwan.

“It is a relationship-driven community, and city, that is extremely hard to break into, but what I’ve discovered is that once you’re in, this is the most helpful and generous city for business that you can be in,” Kwan said.

“People have been in your shoes and they want to help.”

Like Kwan, who was attracted to New York because she saw the city as a global centre for real estate, Williams came to New York because she saw Manhattan as the media capital of the continent, if not the world.

Being in the city is vital, Williams stressed.

(Image: Nicole Williams Works principal Nicole Williams walks in Times Square after meeting BIV | Glen Korstrom)

After many months of pitching investors for cash, Williams was at Saks Fifth Avenue when she received a phone call from Michael Loeb’s executive assistant.

Loeb had co-founded Synapse Group, which developed and patented a system of negative-option billing for magazine subscriptions, and he sold the venture to Time Inc. for hundreds of millions of dollars in the early 2000s.

“Can you be here in 10 minutes?” the assistant asked, Williams recalled.

She dropped everything, got in a cab and beelined it to Loeb’s office, knowing that if she did not show up, the opportunity could be gone.

“If I had to get on a flight and fly from Vancouver to New York City, I would have lost that opportunity,” she said.

Loeb initially invested US$1 million to buy 40% of Williams’ company and later purchased a further 15%. He also provided Williams with a fraction of 1% of his own company, Loeb Enterprises – a stake that she says has been more lucrative than her own venture.

Navigating the complexities of U.S. immigration channels

Matt Friesen had an easy time getting his first U.S. visa.

The company that he founded with three others, Wantering, acquired Los Angeles-based StyledOn in June 2014. The undisclosed investment was significant enough that the U.S. government deemed Friesen eligible for an investor-class E-2 visa, which is normally granted to executives at firms that invest at least US$100,000 in a U.S. company.

Little did Friesen know that the visa would soon go “up in smoke.”

Friesen’s first extended visits to New York City from Vancouver were about a year before the StyledOn acquisition.

(Image: Wantering co-founder Matt Friesen now lives in New York City | submitted)

He saw Manhattan as the centre for media and fashion and knew it was necessary to be there. Wantering was an e-commerce site that enabled visitors to browse and shop at more than 125 fashion retailers from across the web, and Friesen decided that he had to meet fashion industry insiders.

He was helped out financially by being part of the Canadian government’s Canadian Technology Accelerators program.

That initiative provides subsidized office space and helps entrepreneurs find investors and other business opportunities.

Wantering expanded rapidly in B.C. after its 2011 launch, thanks to help from the GrowLab Ventures Inc. accelerator program, angel investors such as Mike Edwards and financing from venture capitalists at firms such as Yaletown Venture Partners.

Finally, in late 2015, Who What Wear parent Clique Media Group made Friesen and his partners an offer to buy Wantering that they deemed too good to refuse. Terms, however, remain confidential.

Friesen’s visa was tied to Wantering, so it was revoked when his involvement with the company ended.

“There is a window after that happens and you’re allowed to stay in the country,” said Friesen, who is now 38.

“I took advantage of that for, let’s say, half a year. There’s some grey area around how long that is but what’s important is that you’re on a track to try to get a new visa.”

Friesen worked with lawyers and was able to stay in the U.S. by creating Into the Awesome, a U.S.-based shell company, and injecting a “significant” enough amount of money into it to qualify for a new E-2 visa.

Williams, in contrast, went through a different process to get her O-1 visa, which goes to people who have an extraordinary ability in science, art, education, business or athletics.

“You’re literally proving that you’re bringing talent to the U.S. that would not otherwise be here,” she said.

“You have to have letters of recommendation. I had to prove my book contract and TV contract. I’m a permanent resident now, but it was very hard.”

Vancouver-based immigration lawyer and Dorsey & Whitney LLP partner Jeffrey Peterson told BIV that the immigration system is challenging for solo entrepreneurs and those who have small home-based businesses.

In addition to the E-2 visa that Friesen obtained, Peterson said that another commonly used visa class is L-1, which requires, among other things, maintaining an established Canadian workforce and establishing a U.S. workforce.

“The larger and more established the business is in Canada, generally the easier it is to transfer employees to the U.S.,” he said.

“Startups and sole proprietorships often can’t qualify or struggle to prove they qualify.”

When Kwan decided in 2015 to stop her frequent visits to Manhattan and to make the city a home, she was able to make the immigration leap because she was born in Houston and was a U.S. citizen, albeit one that had not lived in that country for very long.

Li Chiang still makes extended trips to New York that are interspersed with being at home in Vancouver but, because she married a New Yorker in May, it is easier for her to live in the U.S.

Entrepreneurs who make repeated trips to New York and are not up front about why they are frequenting the city may run into trouble, Peterson said.

“The last thing one wants to do is commit criminal immigration fraud by lying about the reason one’s going to the U.S.,” he said.

“If it is a business trip and one says otherwise, they might not be going to the U.S. for many years.”

Before you go

Gaining traction in New York can be vital for a company to reach a global audience but many pillars of support in Canada make Vancouver the ideal place to launch and incubate an enterprise.

Friesen told BIV that in addition to using the Canadian government’s CTA program, he also used the Canada Revenue Agency’s Scientific Research & Experimental Development (SH&RD) program and the National Research Council’s Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP).

The SH&RD program provides tax credits that can drastically reduce a company’s tax bill whereas IRAP provides advice, grants and access to a network of industry experts.

“If you’re a Canadian-controlled company, you’re eligible for SH&RD, IRAP and the Canadian Technology Accelerators program,” he said.

“That was key to our structure. Our Canadian corporation owned our U.S. subsidiary. Had I done it the other way around, with the U.S. company owning a Canadian subsidiary, I would not have been eligible for those programs.”

American investors often feel more comfortable investing in U.S.-based companies, Friesen said, but he was able to convince them that Canadian companies are worth investing in.

“I told them that if they give me US$1 million, it turns into US$2 million when I walk out the door because of the programs,” he said.

Friesen kept an office in Vancouver after he expanded to the U.S. mainly for the tax credits but also because the city has lower labour costs than New York and he finds that workers can be more loyal to their employers, he said.

Kwan agreed.

“There’s no better place to start a company than in Canada,” she said.

“There’s SH&RD, IRAP, salaries are reasonable and there’s one thing that you can’t buy: loyalty."

Manhattan’s non-stop and unrelenting work culture fosters a climate where employees are constantly looking for the next best thing, she said.

“In Vancouver, employees think, ‘Hey, I really love this. This is my life. How can I contribute?” she said.

“The flip side, though, is that you have people who don’t want to work overtime or don’t want to work weekends but salaries reflect that.”

Entrepreneurs might also want to check out the Greater Vancouver Board of Trade’s new Trade Accelerator Program, which is an intensive set of workshops where experts in the export sector mentor participants during a four- to five-week period and help the entrepreneurs draft an export plan.

(Image: U.S. consul general to B.C. and Yukon Katherine Dhanani's team helps Canadian companies that are seeking to open a new sales office in the U.S. | Rob Kruyt)

Consulates are another place to turn to get help when expanding from Vancouver into the U.S.

The Canadian consulate in New York City provides advice and connections while also holding some events that entrepreneurs might find valuable for networking.

The U.S. consulate in Vancouver is also keen to help.

“Whether a Canadian company seeks to build a new plant or open a new sales office, we have the resources to connect them to key partners in every city, state, and region of the United States,” said Katherine Dhanani, who last month became the U.S. consul general for B.C. and Yukon.

| This is Part 2 of a two-part series on Vancouverites and B.C. companies in New York City. Part 1 in this series, was B.C. retailers that have set up flagship stores in Manhattan. |