When provincial and federal Indigenous relations ministers locked themselves in a room February 26 with Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, one of the goals was to defuse the protest bomb planted over the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

Four days later, they emerged from their meetings having made no progress on the pipeline protests.

“We’re not standing down,” said Molly Wickham, governance director for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en. “We’re not asking other people to stand down.”

But they did announce their intention to settle, once and for all, the question of Wet’suwet’en Aboriginal rights and title – something that many would agree is long overdue.

The agreement, which must be ratified by the Wet’suwet’en, is a commitment to a process to formally recognize and legally implement Wet’suwet’en rights and title.

That won’t happen overnight, and it won’t stop the Coastal GasLink pipeline from being built.

Premier John Horgan has made that clear. The pipeline is permitted and will be built, he has said. And the Supreme Court of Canada has made it clear that Aboriginal title is not absolute and can be justifiably infringed for projects deemed to be in the public good.

But implementing Wet’su-wet’en rights and title could mark a significant milestone in reconciliation. It could also strengthen the Wet’suwet’en’s position in future resource development projects.

As of last week, no one but the hereditary Wet’suwet’en chiefs had seen the proposal, which raised numerous questions.

Is non-Aboriginal private land on the table? Will elected Wet’suwet’en band councils have a say on the agreement?

What will it mean for forestry companies with provincial tenure when Crown land is transferred to the Wet’suwet’en? What will it mean for non-Indigenous hunters and anglers?

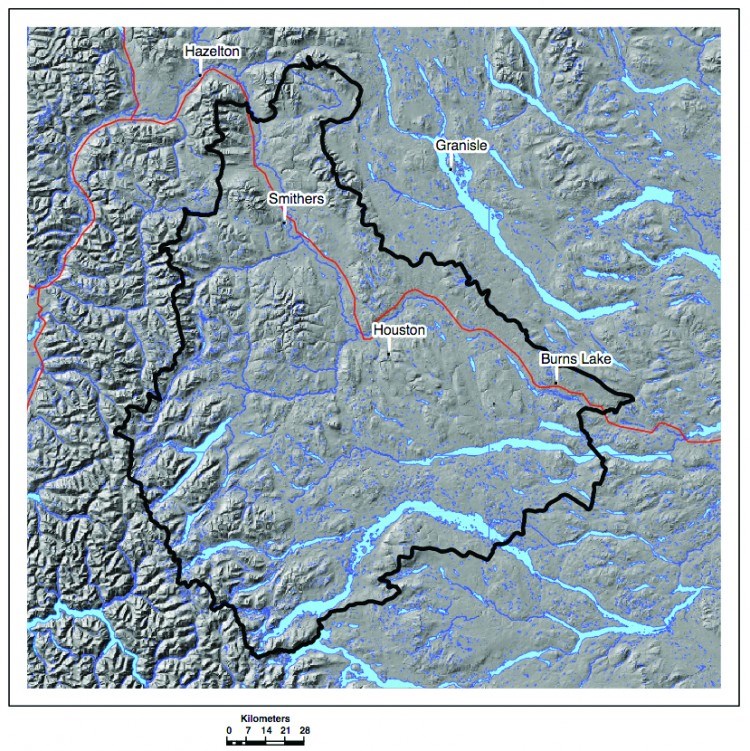

What will it mean for the towns of Smithers, Burns Lake and Houston, which are in the asserted Wet’suwet’en territory? Who will be responsible for public roads, utilities and policing on title lands?

“A key question would be how third-party interests are going to be identified and considered,” said Robin Junger, an Aboriginal-law expert at McMillan LLP.

Burns Lake Mayor Dolores Funk said she hopes that communities like hers will be consulted.

“The willingness to work towards an agreement at the federal and provincial levels and honour a court ruling that happened years ago is, of course, a positive step forward,” she said. “The challenge is that communities, such as Burns Lake, are being left in the dark and have very little idea how this will impact us, socially and economically.”

Scott Fraser, B.C.’s minister of Indigenous relations and reconciliation, told Business in Vancouver that private land is not on the table and that elected band council members will be included in the process.

“My understanding, and my expectation, is that the community, including elected leaders, are all involved,” Fraser said.

There are some concerns that implementing rights and title outside the B.C. treaty process could further erode that process. After all, why would First Nations spend decades and millions of dollars negotiating a treaty when a few roadblocks can expedite the process of at least addressing Aboriginal title?

Kim Baird, who was chief when the Tsawwassen First Nation negotiated a treaty agreement, said the treaty process is much more comprehensive than mere recognition of title.

“The treaty is the most comprehensive way to resolve these things because it does include things like jurisdiction, not just rights and title,” she said.

Given that the Gitxsan were part of the Delgamuukw decision that set the stage for the Wet’suwet’en proposal, it’s reasonable to ask if they might be next to abandon the treaty process and demand that governments recognize their rights and title, too.

But Gordon Sebastian (Luutkudziiwus), executive director for the Gitxsan Treaty Society, said the Gitxsan have no plans to pull out of the treaty process.

And as far as the Gitxsan are concerned, they don’t need senior governments to recognize their Aboriginal “ownership” and jurisdiction. They are acting on the assumption those rights exist.

“We don’t need their recognition,” Sebastian said. “We got it. What they have to do is negotiate [access] with us.”

One way the Gitxsan are exercising their rights is by banning all sport fishing at fishing holes they say belong to specific houses on rivers, like the Skeena, Nass, Kispiox and Bulkley.

What would Wet’suwet’en title look like?

To illustrate what aboriginal title might look like, the Tsilhqot’in example offers some hints. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed the Tsilhqot’in had proved ownership of about 2% of their traditional claimed territory.

As a result, all Crown land in that title area is no longer Crown land – it belongs to the Tsilhqot’in and is owned communally.

That has introduced some uncertainty for forestry companies like West Fraser Timber Co. (TSX:WFT), which owns sawmills in the Williams Lake and Quesnel area, although it didn’t hold any cutting rights in the Tsilhqot’in title area.

In its 2018 annual report, West Fraser warned shareholders that “there is a risk that other aboriginal groups may pursue further rights or title claims through litigation, or treaty negotiations with governments.

“It is difficult to predict how quickly other claims will be litigated or negotiated and in what manner our Crown timber harvesting rights and log supply arrangements will be affected.”

Asked how much things have changed since the Tsilhqot’in title was affirmed, Tsilhqot’in Chief Joe Alphonse said, “Not much.”

For all intents and purposes, the only thing that has changed is a land title, although Alphonse added: “Having title gives us more leverage at the negotiating table.”

The 2014 William decision may have strengthened the Tsilhqot’in’s hand in their fight against the New Prosperity mine. The federal government has twice rejected an environmental permit for the mine, and the strength of the Tsilhqot’in’s land claims no doubt played a part in those decisions.

While the Tsilhqot’in decision offers some insights on what Aboriginal title looks like, it differs in one significant way from the Wet’suwet’en: the Tsilhqot’in are unified under a central, elected government.

“No matter what position that we’ve always taken in Tsilhqot’in, the one thing I can always say is we’ve been unified on that,” Alphonse said.

The Wet’suwet’en have no central government or constitution. They are quite literally divided when it comes to governance. There are both elected band councils and a hereditary house and clan system that has been recognized by the courts as a legitimate traditional form of government. Those two decision-making bodies are at loggerheads when it comes to the Coastal GasLink pipeline. Moreover, some Wet’suwet’en question the legitimacy of some of the hereditary chiefs who are opposed to the Coastal GasLink pipeline and who were involved in negotiating the recent agreement on rights and title.

Three female chiefs had their hereditary titles stripped from them for supporting the Coastal GasLink pipeline and for lobbying for a more centralized decision-making system.

Those titles were handed to members who oppose the Coastal GasLink, including Frank Alec (Woos), who received his title after it was stripped from a female chief, Darlene Glaim. Alec has emerged as a spokesman for the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs.

Theresa Tait-Day was also stripped of her title. She is happy to see a proposal to recognize Wet’suwet’en rights and title. But until the Wet’suwet’en are unified under a central governing system like the Tsilhqot’in’s, Tait-Day said, the discord among the Wet’suwet’en will continue.

“We can sort out the title question, but we need a system of decision-making, first of all, as a nation that is inclusive and democratic.”

Maureen Luggi, elected chief of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation band council, agrees. Once the process for implementing Wet’suwet’en title is set in motion, she said, the Wet’suwet’en people need to address governance issues.

“I’ve never had a say in what they’re doing right now,” she said. “Our children’s lives are at stake here, and we don’t want somebody else negotiating for our kids when we are the ones that are doing the caretaking and managing of our communities right now.”

Scott Fraser, B.C.’s minister of Indigenous relations and reconciliation, said he expects that governance will be addressed in the process for recognizing rights and title.

“The issues of governance need to be addressed as part of this process,” Fraser said. “Clarifying that governance will be a great help to everybody.”