Buying out all the properties built in an old Abbotsford, B.C., lakebed hit by devastating floods in 2021 could cost nearly $1 billion. But that’s less than half of the $2.4-billion cost of the most expensive option put forward by the municipality to ward against future floods, a new study has found.

The research, published Monday in the journal Frontiers of Conservation Science, brought together researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC), West Coast Environmental Law, two B.C. conservation groups and the Semá:th (Sumas) First Nation. Together, they weighed the benefits of returning Sumas Lake to nature to avoid another destructive flood event like that seen in 2021.

The conventional response to a major flood event has meant more hard infrastructure, including ever higher and more expensive dikes. But that path has become increasingly untenable as climate change increases the risk and cost of protecting communities from more powerful and unpredictable floodwaters.

That has pushed planners and communities in high-risk flood zones to consider what once may have seemed unthinkable. Through “managed retreat,” residents voluntarily move off their land and out of the path of floodwaters. Governments then step in to buy out their mortgages and help return the lake to its natural state.

But until now, nobody has investigated how much such a plan would cost, and how residents of the Abbotsford flood zone would receive fair compensation.

Riley Finn, the study’s first author and a researcher at UBC’s Conservation Decisions Lab, said their analysis shows the initial cost of managed retreat is in “the same ballpark” as the cost to continue protecting the prairie. He also warned that after more than a century of homesteading and farming, no path would be easy.

“When it comes to deciding on a path forward for this region, it's going to be significant costs for society, no matter which way we go,” Finn said.

The UBC researcher said his team did not seek to present a complete cost and benefit analysis of retreating from the lake versus continuing to protect the prairie as it is. They also did not speak to the City of Abbotsford or any of the residents of the Sumas Prairie.

Raising the prospect of managed retreat, the report said, is “intended to start this discussion.”

In a statement, Abbotsford Mayor Ross Siemens says returning Sumas Lake to its natural state would risk undermining the “most productive agriculture land in Canada” — one that generates “$3.83 billion in economic activity each year and supports 16,770 local jobs.”

“Abbotsford has the most productive agriculture land in Canada and on a per hectare basis, is the top agriculture producer,” said Siemens.

“A large majority of food production takes place in Sumas Prairie. Reflooding Sumas Lake would mean losing that premium agriculture land and would significantly impact our provincial food supply.”

'Lifeblood' of the Semá:th people

Clearly a controversial proposal, Finn says the success of managed retreat depends on how you weigh its benefits and who will receive them.

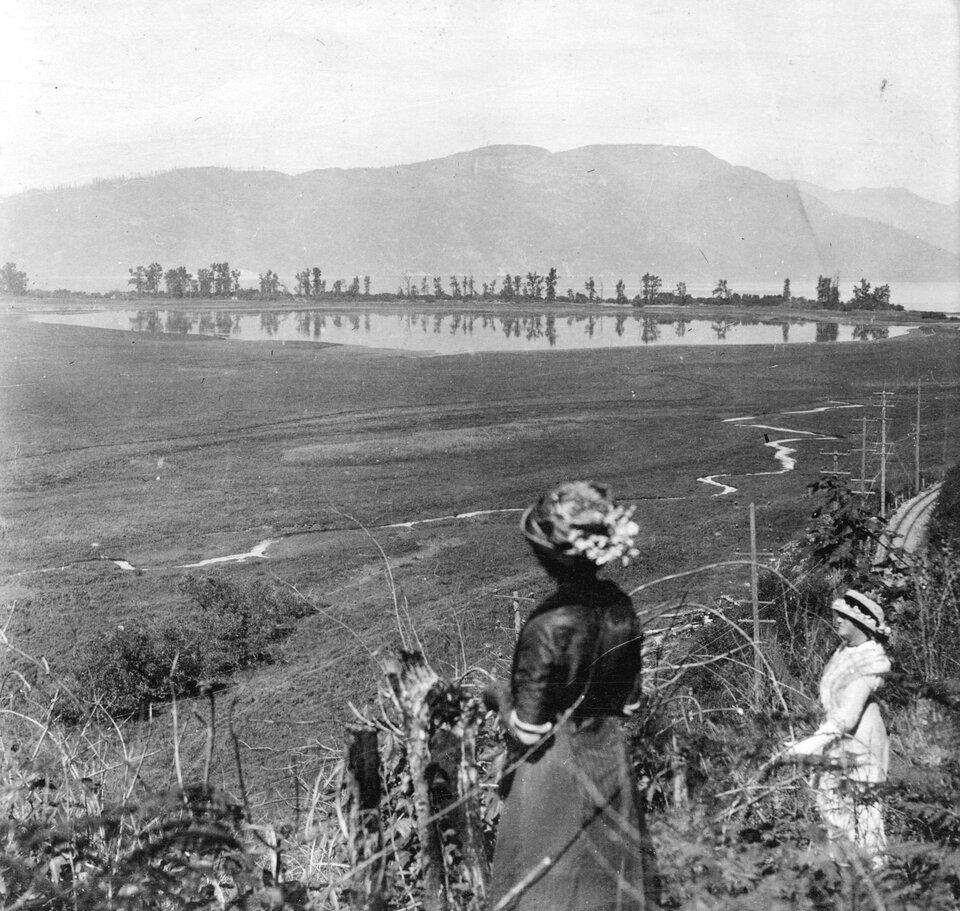

A hundred years ago, Sumas Lake ebbed and flowed with the seasons, by some estimates spanning more than 100 square kilometres and reaching up to 11 metres deep.

For thousands of years, the lake provided for the people that called it home. Along its shores, wild hazelnut, roses and strawberries mingled with wapato, or wild potato. In stories handed to him from Semá:th elders, Chief Dalton Silver described the role the lake played for his people in one word: “lifeblood.”

“Every species of salmon and other aquatic species, right from crayfish to eels to sturgeon to freshwater mussels — not to mention the birds, the ducks, the geese,” said Silver. “There's stories about people going in on canoes and clapping their hands and having the sun blocked out by the amount of ducks that were flying up. The waterfowl was just incredible.”

Silver said the abundance of the lake was at the centre of his people’s life and culture. It provided food security for his people and for their neighbours. In 1924, that natural bounty came to an end when engineers from the colonial government built a pump station, dug a canal, and redirected the Sumas River behind more than 40 kilometres of dikes, according to a 1991 thesis from Queen’s University student Caroline Berka.

By 1925, a lake that once occupied a footprint nearly 16 times that of nearby Cultus Lake had been completely drained.

“It was a huge, huge resource and a huge, huge loss for people,” Silver said.

The Semá:th people were pushed onto nearby reserves, dispossessing them of their former territory in a process that opened up the area to intensive agriculture now known as the Sumas Prairie.

Over the intervening 100 years, the prairie became one of the most intensively farmed pieces of land in Canada. Today, the Sumas Prairie provides nearly all the vegetables for the City of Abbotsford, produces more than half the potatoes grown in the Lower Fraser Valley, and is a major source of dairy, chicken and eggs for the entire region.

But all those harvests come with the risk. With enough rain, flood defences could fail. Under the right conditions, Sumas Lake could return.

'An unwillingness to change'

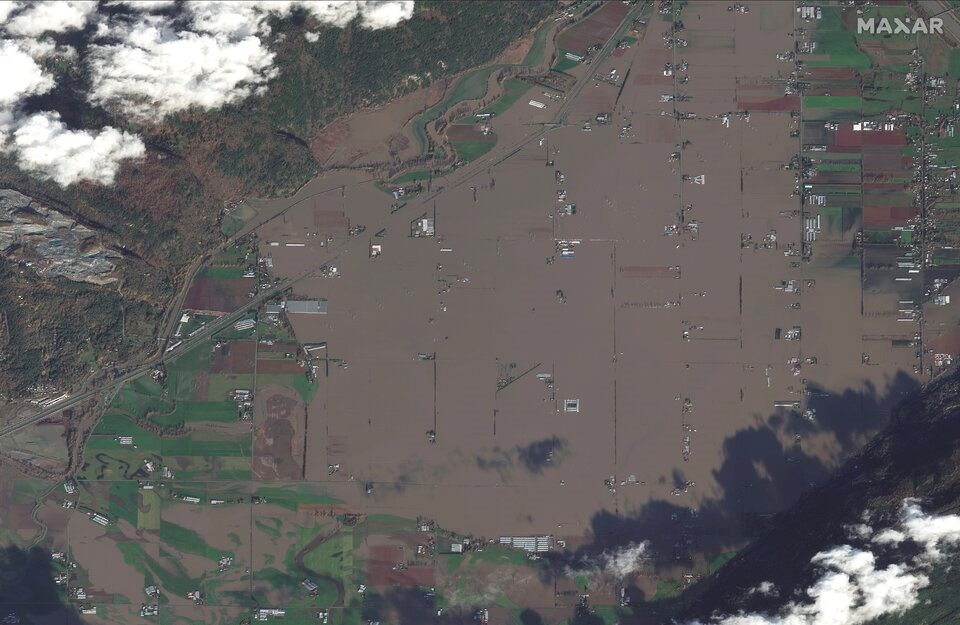

In November 2021, an atmospheric river dropped up to 400 millimetres of rain on British Columbia in 48 hours. The rains — which scientists later found were made 60 per cent more likely due to climate change — swelled the nearby Sumas and Nooksack rivers. When they burst their banks, dikes and pumps meant to protect the community failed.

Water rushed onto many of the properties built on the old Sumas lakebed. As emergency workers and neighbours rushed to evacuate 3,000 residents from the floodwaters, 670,000 livestock drowned. The resulting contamination floodwaters were later found to have left a toxic footprint of fecal coliform, fuel, heavy metals, pharmaceuticals and cocaine.

The failure of Sumas Prairie’s flood defences had been identified by engineers years earlier. A 2015 engineering report from Northwest Hydraulic Consultants found that the largely 20th century hard infrastructure meant to channelize, dike and control the flow of the nearby Sumas and Nooksack rivers was in “unacceptable” condition and failed to meet provincial standards.

Sumas Prairie is not alone. The 2015 report found none of the Lower Fraser’s 74 dikes met provincial standards. Despite the warnings, three years after the devastating November 2021 floods, many of the homes people fled remain at risk. And plans to protect the community have largely relied on status quo flood defences, according to Finn and his colleagues.

Add human-caused climate change to the mix — a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture meaning more frequent and more intense heavy rainfall — and the integrity of the region's flood defences are expected to be further challenged. Inadequate funding, poor maintenance and incorrect design assumptions mean existing weaknesses continue to be magnified by climate change, the study says.

As the authors put it: “A decline in community resilience has been linked to an unwillingness to change in the face of a new problem.”

City’s plans don’t consider ‘managed retreat’

In its response to the floods, the City of Abbotsford worked with an engineering firm to propose four flood recovery plans that are estimated to cost between just over $200 million to more than $2.4 billion.

The city’s cheapest option is to continue with existing flood defences while enhancing the existing Barrowtown pump station. At $909 million, the second option adds a new Sumas pump station. The last two plans range from $2.1 to $2.4 billion and build on the previous options with new floodways and a water storage area. None of the estimates includes the cost of damages from future flooding.

By comparison, buying out all the land and structures within the historical boundaries of Sumas Lake would cost just over $956 million, the study found using provincial land assessment data from just before the floods.

Retreat could require new dike infrastructure. Planning, communication and cleanup costs could also raise the final price tag, the study notes. But according to a systematic review of U.S. floodplain buyouts cited in the study, about 80 per cent of the costs usually come from the purchase of land.

When asked why Abbotsford hadn't considered a managed retreat scenario, Mayor Siemens pointed to the municipality's agricultural output, which he said includes 50 per cent of dairy, chickens, turkeys and eggs consumed in B.C.

“As a municipality, our responsibility is to ensure that our community infrastructure protects our community and residents — this is our legislated responsibility under the Local Government Act and Community Charter — which is why we are looking at flood protection measures versus re-flooding options,” said Siemens.

“Re-flooding would be an entirely different direction and one that would involve all governments. Our focus remains on flood protection.”

Buying out properties to make way for floodwaters is not a new idea. Grand Forks, B.C., demolished 70 homes to make way for flood defences after major floods in 2017 and 2018. And in the province’s Peace region, BC Hydro purchased vast tracks of private land to make way for a reservoir for the Site C hydroelectric dam.

Finn said the properties in the old Sumas lakebed have been flooded and have received multiple insurance claim payouts. The so-called repetitive loss properties could face further financial pressure, say experts.

Climate change is raising the risk of flooding so much that soon many people in high-risk flood zones won’t be able to get insurance, said Rob de Pruis, the Insurance Bureau of Canada’s national director of consumer and industry relations.

“If we look at back in 2021 to the atmospheric river, essentially all of the areas that were impacted were already having some challenges accessing either affordable or available flood insurance at the time,” he said.

Without insurance, some people might not be able to sell their properties.

“Obviously, there are people's homes and that's important, and people don't necessarily want to move,” said Finn. “[But] maybe this is an opportunity for them, rather than a cost to them,” said Finn.

“Why should the people who are there now have to also bear the risk of that happening again?”

Lake could create a 'battery' to hold floodwaters, benefit wildlife

Relying on Indigenous oral histories and law, the study paints an alternative plan to protect people and property while at the same time revitalizing a historic ecosystem and redressing past injustices against the local Sumas First Nation.

Today, more than 85 per cent of the Lower Fraser’s floodplain habitat and 64 per cent of its streams have been lost since European settlement, past research has found. The Semá:th First Nation has never been compensated for the loss of the lake that “was everything” to them.

Bringing back Sumas Lake could offer a significant step in restoring the biodiversity that once existed — of the 102 species at risk in the Lower Fraser today, 72 are likely to have inhabited Sumas Lake, the study says.

“This is a massive area for rearing salmon,” said Finn. “It could be used as a way of managing floodwaters throughout the lower Fraser, as a storage area and a battery to hold those high water level events.”

As chief of the Semá:th First Nation, Silver said he recognizes the prospect of removing people from their land “puts the fear into the general public.” But he said the Semá:th know what it’s like to be dispossessed of their land, and it’s not something they want to inflict on others — especially when many residents are considered close friends.

“We don't have the intention of removing people from their homes,” he said. “Some of these people have been there several decades, some maybe near a century, whereas we were on our homelands throughout the millennia, how many we don't even know. And then to be removed from our homes, that's a hurt, that's still there,” Silver said.

“That's something we're still healing from. So we really don't want to wish that on people.”

Silver said that any plan to buy out property owners in Sumas Prairie would have to involve a “willing seller.”

When asked how his nation would respond if residents say no and governments chose to protect Sumas Prairie with traditional flood defences, Silver said he would hope it leads to “really abundant” crops and the land providing today as the lake did for his people in the past.

And if the lake is returned, Silver said he’s confident the species that once called it home would return.

“I think the fish always seem to know their way back,” he said.

Editor's note: This story has been updated with comments from Abbotsford Mayor Ross Siemens.