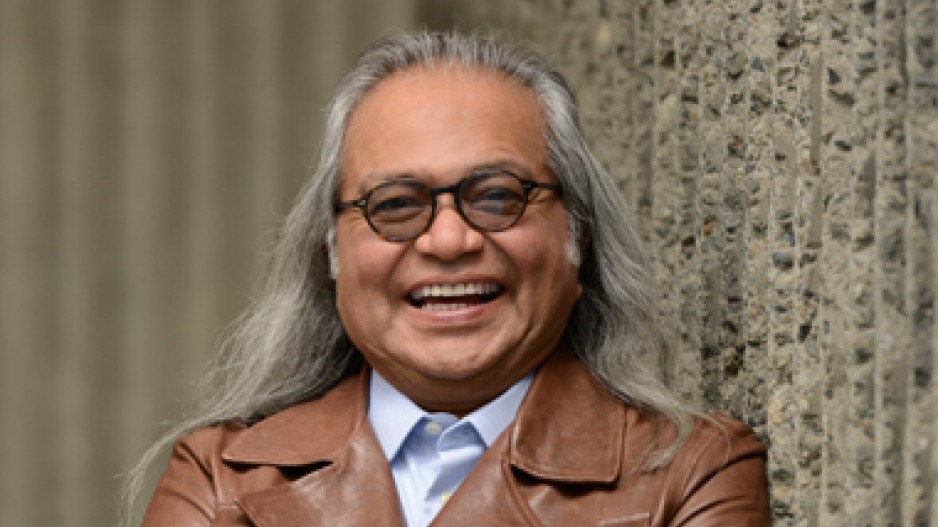

Manny Jules doesn't look much like an agent of free-market capitalism.

On a rainy day at a swanky downtown hotel cafe, the former Kamloops Indian Band chief is seated quietly at a table, drinking mineral water. He has long silver hair and round tortoiseshell glasses, through which he peers intently as he explains the ideas that have made him a target of Idle No More activists.

"What really drove it home to me was sitting, thinking about: How come we don't have what everybody else has got?" he says.

Jules, 60, is chief commissioner of the First Nations Tax Commission, a government-funded agency that promotes on-reserve property taxation powers.

He's also an advocate of private property rights on reserves, a position that has put him at odds with the Assembly of First Nations. In 2010, the AFN passed a resolution against legislation he helped to create, saying such legislation would "impose the colonizer's model on our Peoples" and could lead to reserve lands passing out of the hands of aboriginal people.

Idle No More activists go further, warning that private property rights could lead to land grabs by oil and mining companies.

Jules counters those concerns by saying that any workable legislation would have to be optional, and that First Nations would retain the underlying title to reserve lands.

The federal Conservatives have been a supporter of the idea (in 2010, Tom Flanagan, a former adviser to Stephen Harper, co-authored a book on aboriginal property rights, for which Jules wrote a foreword.) In the fall of 2012, the government introduced the First Nations Property Ownership Act, based in part on Jules' recommendations.

"Her Majesty owns the lands, and she grants rights of possession to Indians," said Jules. "So you can have possession rights on the reserve, but that doesn't mean you can take that to a bank and get a mortgage to build your own home. It doesn't mean you can be bonded, because you don't own your own home."

Despite the considerable opposition, Jules remains steadfast in his belief that property ownership is one way to lift First Nations people out of poverty. But he knows from experience that the process of changing minds can be very long.

The property bill is still working its way through Parliament, but, since 1992, another piece of legislation Jules championed has been in effect. The First Nations Fiscal Management Act gives band councils the option to choose to collect taxes that would otherwise flow to provincial or municipal coffers. Currently, 170 First Nations, primarily in B.C., have voted to adopt the tax measures.

"On reserves, it's primarily the leasehold interests that are taxed," said Jules. "It's either a linear structure – a pipeline going through a reserve – or with [BC] Hydro, there's an easement agreement, a business relationship as opposed to a tax. With businesses, because they have a lease, they're taxable."

The fight for the ability to collect tax goes back long before 1992, however. For Jules, it all started in 1963 on a snowy road that led to an industrial park on the Kamloops reserve.

Jules was born in 1953 in Kamloops, one of nine children. He attended the Kamloops residential school (by that time, students were not required to live at the school). In the 1960s, he attended high school in Kamloops, part of the first wave of post-residential school integration.

"My mother always told me, when you were born, I had a horse and your dad had a saddle, and then we had you," said Jules. "For the first few years we didn't have our own house."

In 1963, Jules' father, Clarence Jules, set up the first industrial park located on a Canadian reserve. Around 14 businesses set up shop in the park, but in winter, Jules' father, who also served on the band council, had a tough time getting anyone to plow the roads. The problem came back to taxes.

"Phil Gaglardi was the minister of highways at the time, so Phil said, 'Oh sure, I'll come and plow the roads,'" Jules related. "Then a little while later he said, 'Clarence, can't plow the roads, you're a federal responsibility.' And so my dad went to the federal government, and they told him, you can't come to us, because we don't collect the taxes, the province does."

While he had initially planned to be a sculptor, Jules followed in his father's footsteps and ran for band council in 1974; he was chief from 1984 to 2000.

Taxation was always top of mind. "We put forward what was called the Kamloops option, which was if we adopt a bylaw under the Indian Act, will the provincial government vacate the tax field," said Jules. "And of course they wouldn't."

The band challenged the status quo in court but lost the case.

"It meant that the lands that were set aside for commercial developments were not really part of the reserve ... Therefore the band and the band council had no jurisdiction over it, only ... [federal] cabinet," said Jules.

"It meant you couldn't manage your lands, you couldn't have bylaws, you couldn't have enforcement, renewal of leases, the normal day-to-day stuff."

The next target was changing the Indian Act itself, a process that took seven years and required legislation changes at the federal and provincial level.

Since 1992, he said, transferring taxation powers to bands that choose to exercise the legislation has generated $1 billion in revenue.

"It means you don't need to use your revenue to provide services," said Jules. "You can collect tax to provide those services."

The ability to tax is about much more than raising revenue, said Mike LeBourdais, the chief of Whispering Pines Indian Band near Kamloops.

"The authority of any government is its jurisdiction ... If you want to say, we are the Shuswap, or we are the Cree, or we are the Métis or what have you, you have to recognize that jurisdiction and have other governments recognize it," said LeBourdais.

"Otherwise, we would just sit there and gripe about the historical wrongdoings of Canada to the First Nations people."

Jules' ideas "just make sense," said LeBourdais.

"He's quiet, well spoken, well versed and he does his research."

With the AFN no fan of his work, Jules instead focuses on winning over individual First Nations. His successes are hard-won.

"We're a very conservative people," said Jules. "Because we come from an oral tradition ... people have to see how it works."