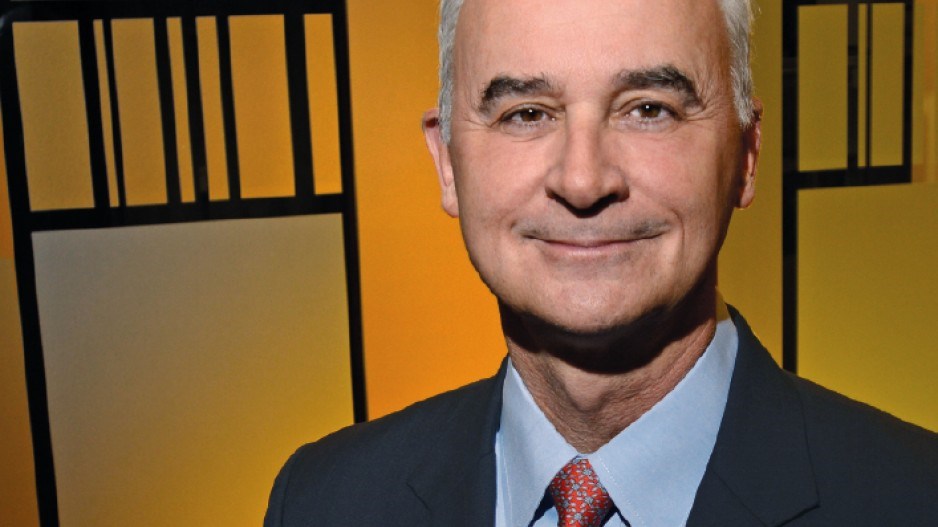

Mike Waites, the son of a car and truck salesman, has always liked engines.

"When I was younger, I never had any money," he said. "I always had beaters, so I was always fixing and rebuilding my cars."

Now as the outgoing CEO of Finning International, the world's largest Caterpillar equipment dealer, "I get to play with some of the biggest reciprocating engines in the world," he joked.

Waites, 60, announced his retirement in January. He joined the company in 2006 as CFO and became CEO in May 2008, just in time to shepherd Finning through one of the roughest patches in its history.

"In August [2008], we went over the cliff," said Waites, relating how the company blew through $720 million of an $800 million credit line in a skin-of-your-teeth bid to wait out the liquidity crisis.

Now, according to Waites, the future looks good again for the iconic B.C. company, which employs more than 15,000 people globally and generated revenue of $6.6 billion in 2012. The heavy-equipment dealer does business in Canada, the U.K., Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Uruguay. Anchored by copper mining in Chile, the company's South American business in particular is booming.

This year, Finning celebrates 80 years of selling dozers and 400-tonne trucks. While mining and the oilsands have replaced forestry as the key sectors the company services, the basics of the business and the company culture have remained the same.

"At the end of the day, when you go to a customer, they have to pick Finning because of the service and support that we give," said Waites.

With training in economics, Waites is used to looking at the world through numbers, a facility he said served him well during the white-knuckle days of the financial crisis.

"Very much today in the world we use business models … to help understand reality," he explained. "And in economics there was a lot of modelling of how economies work … I find it often helps you find solutions that others don't see."

A big believer in shaping your own future, Waites said that having a grasp of a few basic certainties can help businesses get a grasp on the unknowns.

"We know that population is growing in China, that economic development will occur in China. We know that gives support for commodities and base metals, which gives us confidence in our mining business in South America. So we then spend our capital money playing to that future."

Waites grew up in north London; his family emigrated to Canada when he was 13, settling first in Toronto, then Calgary.

"I have never forgotten the fact that I think our family has been enormously fortunate in coming to Canada," he said.

"It's probably not a politically correct thing to say, but I'm not sure Canadians really appreciate that."

Waites was a grad school dropout ("I ran out of money," he admitted) who took a job with Chevron in California. He eventually completed his master's degree and did a night school MBA.

At Chevron, he found a niche working on projects no one else wanted to touch.

"I saw that if people were working on a certain thing that was well taken care of, I probably wouldn't add a lot of value," he said.

"Where could I look around in a business and see a way to create value?"

That curiosity led him to work on the Hibernia oil field, a complex project that required "a great deal of creativity."

"It was a project where we knew we had a large body of hydrocarbon reserves, but it was expensive," said Waites, "and we needed to come up with very innovative ways of developing that project."

Part of the solution involved negotiating with the governments of Canada and Newfoundland for tax and royalty breaks.

At Chevron, he also learned valuable lessons about how acquisitions can fail or succeed. A failed bid for Amax, a large mining company, showed him the importance of focusing on core competencies.

"At the time, it was very much in vogue for oil and gas companies to start calling themselves resource companies. The reality was, oil and gas people have a very different culture than miners."

In contrast, the acquisition of Gulf Oil, a company that was in the same business as Chevron, was a success.

For an example of what a well-thought-out acquisition can do for a company, Waites pointed to Caterpillar's purchase of Bucyrus, a maker of heavy-duty mining equipment such as huge shovels and rotary drills.

Through the deal, Finning now has the distribution rights to the equipment. It has allowed Finning to offer a "complete solution" to its mining customers.

"When Caterpillar bought Bucyrus, they took a very comprehensive mining product lineup and filled in the mining gaps. When you put the two together, you have the complete mining product. Strategically, it's a game changer for us."

Waites is also excited about Finning's growing U.K. business, which now includes using Caterpillar engines in power systems, such as backup electricity generation for hospitals. It's an expertise that has grown out of Finning's experience in the mining sector, where the company developed diesel-powered generators for remote mine sites.

"Today we do that and we feed methane gas instead of diesel into those engines and generate electricity, say from abandoned coal mines or biomass."

These integrated power systems now add up to around $1 billion of Finning's business.

Mauk Breukels, vice-president of investor relations and corporate affairs at Finning, pinpoints Finning's evolving business in the U.K. and the acquisition of the Bucyrus line from Caterpillar as two of Waites' key achievements.

"He's driven investment in our infrastructure to drive our parts and service business forward," said Breukels. "And he's built a really strong management team."