Canadians will pay dearly for the newly completed expansion to the long-delayed Trans Mountain pipeline—$31 billion to be precise.

But the controversial investment isn’t without its economic benefits.

While it is too early to say for certain whether the expansion will result in lower West Coast gasoline and diesel prices, a recent narrowing of the spread between wholesale prices in Edmonton and Vancouver suggests that may, in fact, be the case.

And recent export data suggests that the expansion is already benefiting Alberta oil producers with a significant increase in crude oil exports—including exports to Asia.

Originally built in the 1950s, the Canadian government purchased the Trans Mountain pipeline from Kinder Morgan (NYSE:KMI) and completed the pipeline’s expansion at a total cost of $31 billion.

The expansion involved building a second line parallel to the existing pipeline. This increased the project’s capacity to 890,000 barrels of oil per day from 300,000. The new pipeline is dedicated to crude oil, while the original batched pipeline carries a mix of lighter crude and refined fuels, such as gasoline and diesel.

The expanded pipeline was quietly commissioned at the beginning of May. Since then, there has been a noticeable uptick in exports via oil tanker.

Statistics Canada reports that commodity exports were up 5.5 per cent in June, with crude oil and unwrought gold accounting for more than three-quarters of the increase in the value of total exports.

“While prices for crude oil exports rose in June, volumes were the largest contributor to the increase,” the statistics agency reported. “The higher exported volumes were driven in part by higher exports of crude oil to Asian countries.

“The rise in exports destined to this part of the world reflects increased deliveries of crude oil from Western Canada via the Trans Mountain pipeline, whose expansion was recently completed.”

The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority reported a threefold increase in petroleum products moving through the Port of Vancouver in June, compared to the same period the year before: Nearly 1.8 million metric tonnes in June of this year, compared with 524,265 metric tonnes in June 2023.

“Prior to the expansion project, limited transportation and terminal capacity meant marine loadings averaged two to three vessels per month,” federal government-owned Trans Mountain Corp. said in a statement.

“With our May 1, 2024 commencement of service on the expanded system, we loaded five vessels in May and 21 vessels in June. We have since loaded 22 vessels in July and expect further increases to Q4 of 2024 and beyond.”

It has been reported that most of the exports since May would have been destined to California. However, Statistics Canada data confirms that crude oil exports through Vancouver to Asia increased in May and June.

Whereas $111 million of crude oil was exported to Hong Kong in all of 2022, and $48 million was shipped in 2023, there has so far been $662 million worth of crude exports shipped to China, India and Hong Kong this year.

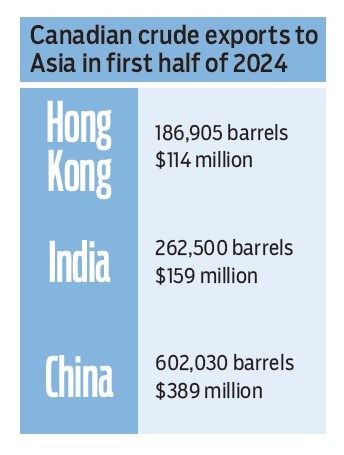

This year, up to June, 186,905 barrels of crude valued at $114 million were shipped to Hong Kong via Vancouver. Another 262,500 barrels valued at $159 million were shipped to India, and 602,030 barrels were shipped to China at a value of $389 million.

That doesn’t surprised Kevin Birn, chief Canadian oil markets analyst for S&P Global.

“There is always a market for crude oil in the Pacific Basin,” he said. “We always saw the need for Trans Mountain pipeline. We saw Canadian production continuing to grow.”

Right now, Asian refiners will be in a test period, he said. They will experiment with Canadian crude that they may not have used before to make sure it matches their refining requirements.

“It’s still relatively early,” he said. “I’d expect volumes continue to build, cargoes to test different markets all over the place, and over time you’ll start to see patterns.

“As we go into winter months, Canada will set new export records, because as capacity’s been optimized and new product projections and wells are brought online, the winter tends to be the peak period. Every year, I think, for the next couple of years, Canada will set new records.”

As for British Columbians, they may be starting to benefit from lower gasoline and diesel prices as a result of the pipeline expansion.

Since its completion, the spread between wholesale prices in Vancouver and Edmonton appears to have narrowed, said Kent Fellows, assistant professor of economics at the University of Calgary School of Public Policy and a fellow with the C.D. Howe Institute.

Last week, Fellows published an analysis for C.D. Howe that explained why the Lower Mainland has had such high gasoline prices compared to other parts of Canada for the last several years.

In recent years, Vancouver has held the dubious distinction of having some of the highest gasoline prices in North America, with price spikes tending to happen in summer. Suspecting that “Big Oil” was deliberately gouging British Columbians with a complex price-fixing scheme, the former John Horgan NDP government commissioned an inquiry into Vancouver’s high gasoline prices.

The inquiry by the BC Utilities Commission (BCUC) concluded that there was an unexplained 13-cent difference between wholesale prices in the Lower Mainland and Seattle, with similar disparities between the Lower Mainland and Edmonton.

But there exists a simpler explanation for this difference, according to Fellows: Pipeline bottlenecks.

The Parkland Corp. (TSX:PKI) refinery in Burnaby supplies less than a third of the Lower Mainland’s gasoline and diesel. The rest comes mostly from refineries in Alberta, via the Trans Mountain pipeline and by rail.

Because there simply wasn’t enough room on the Trans Mountain pipeline for all of the crude and refined fuels that producers needed to ship to the West Coast, pipeline capacity had to be rationed, Fellows explains. And in 2015, the National Energy Board (NEB) made regulatory changes that resulted in crude oil shippers being able to take more capacity on the pipeline, to the exclusion of refined fuels.

Wholesalers ended up having to transport more gasoline and diesel by rail, which is a more expensive method of transportation. As a result, wholesale prices in B.C. began to “decouple” from wholesale prices in Alberta after 2015.

“Insufficient transportation infrastructure, whether an energy pipeline, electricity transmission or any other mode, has actual economic costs,” Fellows said in his report.

He estimated the financial burden of insufficient pipeline capacity roughly cost the B.C. economy an average of $500 per person per year—or close to $1,200 per year for an average B.C. household.

It was hoped that a new pipeline dedicated to crude oil would free up the Trans Mountain’s batched pipeline for more refined fuels. That has yet to be substantiated by the Canadian Energy Regulator (CER), which won’t have data on refined fuel movements on Trans Mountain until the end of this month.

However, the fact that the wholesale—or “rack”—price for gasoline in Vancouver is now only about 12 cents higher than in Edmonton suggests that additional pipeline capacity may be slowly easing prices at the pump.

“The price drop to me is a pretty dead giveaway,” Fellows told BIV.

Before the 2015 NEB changes, there was about a 10-cent difference between Vancouver and Edmonton rack prices, Fellows noted. Sometimes the gap would be within five cents. After the 2015 changes, the gap widened.

“As of 2023, the price difference had grown to between 20 and 35 cents per litre, depending on the city and month,” Fellows wrote in his analysis. “This is a direct result of insufficient infrastructure, specifically the constraints on the Trans Mountain pipeline.”

On August 13, wholesale prices in the Lower Mainland were about $1.08 per litre, and $0.96 per litre in Edmonton—a 12-cent difference.

“That’s dropped pretty significantly over the last couple of months,” Fellows said. “Those prices are a lot closer to each other.”

While that narrower rack price difference doesn’t necessarily prove that more refined fuels from Alberta are now making their way to B.C. thanks to the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, Fellows described it as “a really strong indicator.”

“We won’t know for sure until that data comes out, but I’d be surprised if there’s anything else that’s responsible for this correction,” he added.

Going forward, Fellows expects that wholesale prices in B.C. will remain about 10 cents higher than Edmonton, just due to the transportation costs.

“That puts them in line with a lot of the rest of the country,” he said. “Calgary and Edmonton is going to be a little lower because we’re closer to the refiners. I wouldn’t expect Vancouver to be the outlier that it has been for the last five years.”