For several years, politicians and the mining industry have targeted Canadian regulations standing in the way of feeding a burgeoning critical minerals market.

In advertisements and on its website, the Mining Association of B.C. (MABC) says the country's westernmost province has a “generational opportunity” to supply the world with critical minerals needed for clean technologies. The long-term economic impact, claims the group, could reach $800 billion.

It’s a narrative that has been echoed by Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, and more recently picked up by B.C. Conservative leader John Rustad during the last B.C. election campaign. The only thing standing in the way, according to the MABC, is government red tape.

“It cannot take us 15 years to permit new mines in this country if we are going to achieve the targets that we've set for electric vehicles,” Wilkinson told Glacier Media in 2022.

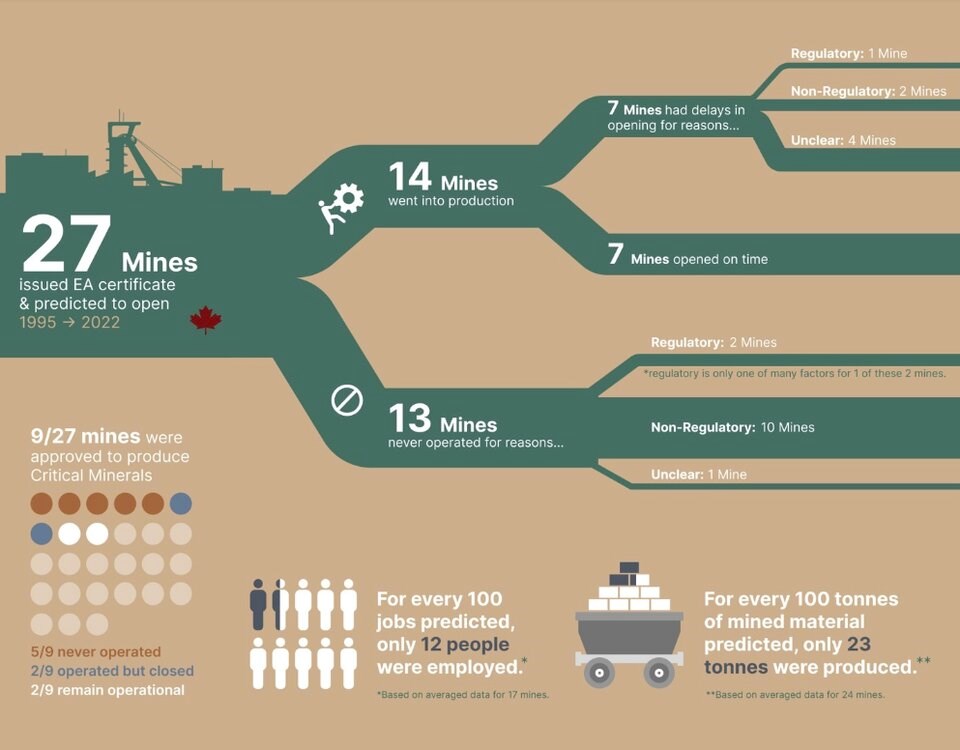

A new audit released Wednesday claims to blow a hole in that story. The study, published in the Royal Society of Canada journal FACETS, brought together researchers from Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia to examine 27 B.C. mines granted environmental assessments since 1995 with plans to open by 2022.

Using public documents, they analyzed initial timelines for mine development and what economic benefits companies said would come from production, employment and taxes. Then they compared those predictions with what actually happened.

Of 20 delayed mining projects, three cited regulation as an impediment to opening. The audit found the most common cause of delay was economic factors like commodity prices — not red tape. B.C. mines were found to take an average of 3.5 years to go through environmental assessment, far less than the 12-15-year timeline cited by Canadian industry and politicians.

Co-author and UBC geography professor Jessica Dempsey said she was surprised to learn only 13 of 27 approved mines actually opened. Most requested permit extensions after they failed to open for some other reason — often due to a lack of financing or the time wasn’t right in the commodity cycle, the audit found.

“These fly directly in the face of this narrative that these mines are delayed by regulation,” Dempsey said.

The audit's conclusion: the B.C. government is approving mining operations that aren't economically viable.

The audit also found B.C. mines regularly failed to meet their economic forecasts. On average, production fell 77 per cent below company predictions; employment was 82 per cent lower than what was forecast; and tax revenue sunk 100 per cent below expectations, according to the researchers.

Rosemary Collard, a co-author and SFU associate professor of geography, said their findings have significant consequences for the B.C. public, the province’s economy and its environment.

“It's very appealing right now to look forward with dollar signs in your eyes at the cash cow of critical mineral mining,” said Collard.

“But if you look at the present critical mineral mines that are operating in B.C., you see that they are not producing that big money. They're extremely boom and bust.”

Audit an 'incomplete picture' of mine permitting in B.C., says industry head

MABC president and CEO Michael Goehring said the audit “appears to be an incomplete portrayal” of major mine permitting in the province.

Goehring pointed to two recent mine approvals in B.C. he said took eight and 11 years to get approved. The mine permitting process, he added, “takes far too long and is fraught with duplication and uncertainty.”

“Each mine is different, but we need the provincial government to streamline the mine permitting process while maintaining B.C.’s world-leading environmental protections,” he said.

Goehring cited survey data that he said showed producers of critical minerals in Canada had a 79 per cent favourability rating among those polled in British Columbia. He said another 91 per cent believed mining is positive for the province’s economy.

The percentage of B.C. residents who supported Canada taking steps to increase its role in mining and producing critical minerals the world needs climbed to 84 per cent this year, up from 73 per cent last year, added the association president.

“To unlock this opportunity, we must act now to modernize and expedite the permitting and approval processes for mining and critical mineral projects,” said Goehring. “If we don’t, the capital needed to grow and maintain the industry will simply flow elsewhere.”

Glacier Media questioned the Ministry of Natural Resources over Wilkinson’s statements on mining regulatory delays. A spokesperson said it could not meet this story’s deadline and would respond within two days.

Industry critics say push to cut red tape ‘very anecdotal’

Nikki Skuce, co-chair of B.C. Mining Law Reform who wasn’t involved in the research, said the latest audit helps “debunk the myth” that cutting regulatory red tape will unleash a bonanza in critical minerals.

“This push to cut red tape, there’s no evidence backing behind it,” said Skuce. “It’s very anecdotal.”

Skuce also said cutting regulatory processes risks a repeat of the disaster seen at the Mount Polley mine — an incident that is still being litigated in court more than a decade after 20 million cubic metres of waste water poured into B.C. rivers.

“Often the trade-off is said to be the jobs and economic benefits. And yet we’re not really seeing those come to fruition,” she said.

Jamie Kneen, a spokesperson for MiningWatch Canada, said he was surprised at how overwhelming the evidence was countering the industry and government policy push around critical minerals.

“You can cut red tape and not make mining more economically viable,” Kneen said. “Those processes were put there for a reason — to protect the environment and public interest.”

Study did not include big coal mines

The study did not look at mines approved before 1995, including several large coal mines in southeastern B.C. A lack of transparent data meant some of their conclusions on tax revenue still need to be tested, the researchers said.

One outlier included the Brucejack mine in the Golden Triangle region of northwestern B.C., where sufficient tax data showed it produced only seven per cent of the corporate tax revenue the company had initially projected.

According to the audit, the Red Chris mine was the only critical mineral-producing mine approved since 1995 that was delayed by regulation.

The delay was the result of a court case that challenged the lack of a full environmental assessment of the project. Collard said it's a good example of how attempts to cut red tape can ultimately slow approval.

No systematic approach to measuring economic benefits

In reviewing the 27 environmental impact assessments, Dempsey said they found no systematic approach and no clear requirements on how to measure economic benefits mines have for the province.

“Even more galling is that they're using models that aren't based in empirical reality,” she said. “They assume this kind of pathway of regular production, when this is like commodities boom and bust.”

The audit found that in many cases, mining permits were handed out to companies that have yet to open operations years later.

And even though minerals are public resources, Dempsey said there is no requirement for mining companies to follow up with government and report on how many jobs and how much tax revenue they actually created.

“We're in a real inflection point,” said Dempsey. “There's so many incentives coming online. But looking backwards, the state of mining in B.C. is one of vast, overstated economic benefits.”

She added: “There are problems all the way along — all fixable problems, though, if the regulator decided to fix them.”