When considering B.C.’s LNG race it’s important to remember the 2011 mining boom that never was.

In those days, I was still in the newsroom sifting through market analyses, commodity reports and drill results while Howe Street’s hard-rock CEOs became the harbingers of the so-called commodity super-cycle.

The gold price in the autumn of 2011 had reached US$1,800 per ounce – and the CEO of Vancouver’s largest gold company told me it could soon be north of US$2,000.

The silver price had reached US$40 per ounce – and the bulls of Burrard said it had room to grow.

The price per pound of copper – a mainstay of B.C.’s mining industry – had topped US$4 and old mines were being revived while other major projects moved forward.

Downtown Vancouver was awash in stock deals, takeovers, mergers, poison pills and white knights.

In B.C.’s northwest a transmission line promised to open up the fabled Golden Triangle of the Stewart-Cassiar, while in the northeast coal mines hummed with renewed activity.

The province even got caught up in the fervor, promising the development of eight new mines in its original jobs plan.

LNG was a blip on the radar.

Fast-forward three years and the gold price has dropped to around US$1,200 per ounce, silver is down to US$17 and copper is US$3 per pound.

Many of B.C.’s operating mines – new and old – have introduced cost-cutting measures and shed staff.

The Northwest Transmission Line was built, but Red Chris remains the only mining project in that region that has become a reality – the capital cost for many of the other Golden Triangle projects remains too steep for today’s market.

And, in the northeast, the industry has shut down thanks to steelmaking coal prices that have bottomed out.

Today, mining does not hold the promise it did three years ago – the focus has shifted to natural gas.

Finance Minister Mike de Jong recently tabled the proposed LNG tax.

Kudos to the province for designing a tax system that, on the surface anyway, appears fair and will generate value for British Columbians should LNG get off the ground and generate profit.

But too much of the media coverage has positioned the tax as the magic bullet or nail in the coffin for the development of LNG in B.C.

It’s neither.

Though tax systems, permits, environmental certificates and impact benefit agreements all have a hand in resource industry development, they pale in importance to global market forces and the almighty commodity price.

Simply put, what does it cost to get the resource out of the ground and to the customer?

And is that cost less or more than the prevailing market price or contracted price point?

In gold mining, it’s called the production cost per ounce of gold.

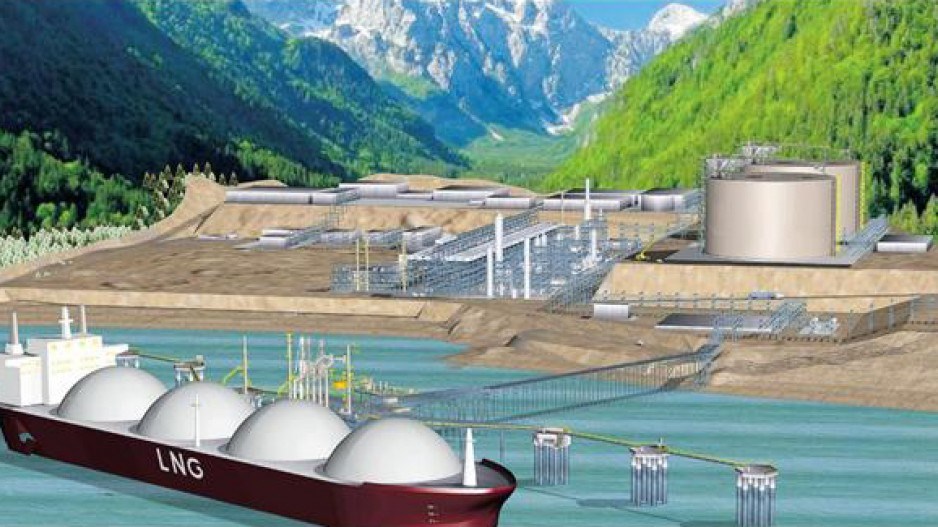

For LNG, the question B.C. needs to ask is: what’s it going to cost per unit to extract the resource from the northeast, ship it to the coast, cool and liquefy it and transport it to Asia for sale?

And what is the price it can be sold for in Asian markets?

B.C. has always been at the end of the demand pipeline in the North American natural gas market, and the U.S. has more than enough of its own supply that it doesn’t want ours.

The only chance for this industry to develop is, and has always been, Asia.

And Asian demand will underpin the price point B.C. can get for its natural gas.

Tax systems, permits, environmental certificates, agreements and partnerships all help resource industries develop – as do political certainty, proximity to market, geography, climate and the ever-nebulous “social licence.”

But make no mistake: the development of LNG in B.C. is entirely dependent on commodity prices and sales contracts.

Just ask the miners.•

Joel McKay ([email protected] ) is director of communications at Northern Development Initiative Trust, a non-profit organization that stimulates economic growth throughout northern B.C. The Jack Webster Award-winning journalist is also a former Business in Vancouver editor.