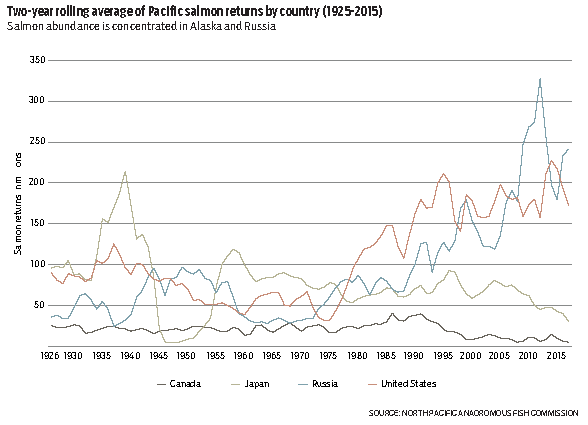

Commercial fishermen caught 651 million Pacific salmon in 2018 – one of the largest catches recorded for an even year, according to the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC).

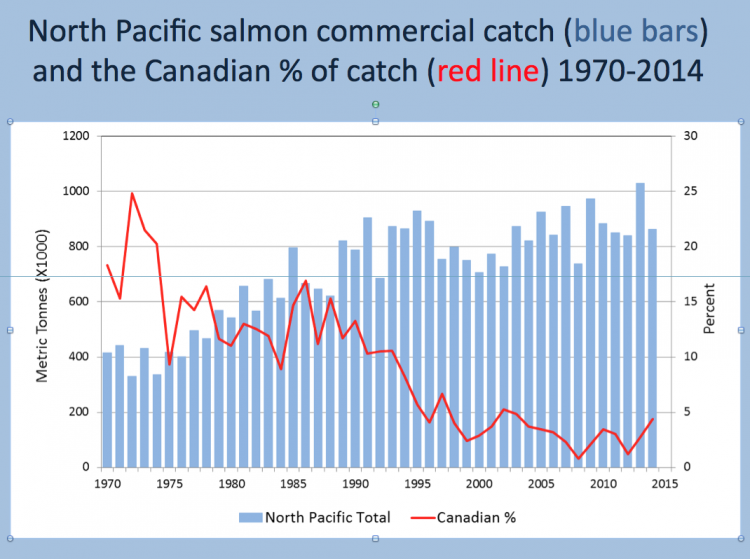

B.C.’s share was a measly 1% – about four million fish. That’s a far fall from the mid-1970s, when B.C.’s share of the global Pacific salmon catch was about 15%.

Of the total 2018 commercial harvest, 55% (by weight) were pink salmon, followed by chum (26%) and sockeye (16%).

Russia claimed 63% of the commercial Pacific salmon catch, followed by the U.S. (27%), Japan (9%), Canada (1%) and South Korea (less than 1%).

Even years typically see lower pink salmon abundance, which is why the NPAFC notes the comparatively high catch numbers for 2018.

2019 is a pink salmon year for the Fraser River. But it is a sub-dominant year, meaning fewer sockeye are expected to return compared with last year.

In 2018, 10.8 million Fraser River sockeye returned, compared with just 1.7 million the year before, according to the Pacific Salmon Commission (PSC). This year’s forecast is for 4.8 million sockeye and five million pink salmon.

The NPAFC’s data on the global commercial catch doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story. It doesn’t include First Nations or sport fishery catch numbers, for example.

Last year, B.C. First Nations caught 1.1 million salmon, of which 274,400 were for First Nations commercial fisheries, according to the PSC. The sport sector’s share was 109,600.

While it may not provide the full picture on salmon returns, the NPAFC’s commercial catch data is a valuable measurement of abundance, and it shows that Pacific salmon abundance has grown since the 1970s, boosted mostly by pink salmon.

The NPAFC’s 2018 numbers underscore the findings of a study published last year by Greg Ruggerone and James Irvine. It concluded that Pacific salmon are more abundant than they have ever been. In fact, Pacific salmon are now almost twice as abundant as they were in the 1970s.

The problem for B.C.’s commercial and sport fisheries is that they’re not the right kind of fish, and they’re not in the right places.

While B.C.’s commercial sector harvests mainly sockeye, the sport sector targets chinook and coho. Despite their importance to the sport fishing sector, coho and chinook are minor species, in terms of population size, compared with pink, chum and sockeye.

Canada’s comparatively lower harvest levels are partly attributed to the fact that other countries are happy to catch pink and chum salmon, while neither species is preferred by commercial or sport fishermen in Canada, said Dick Beamish, scientist emeritus at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ Pacific Biological Station.

Despite a relative abundance of pink salmon in B.C., commercial fishermen are sometimes restricted from catching them to protect weak coho stocks.

But the biggest factor in Canada’s declining commercial catch is declining salmon populations in more-southern regions.

Although there have been periodic rebounds, such as the 28 million sockeye that returned to B.C. in 2010, and some very high pink salmon returns, B.C. salmon stocks have generally been declining since the late 1990s.

Russia dominates north Pacific salmon catch

In 2018, Russia caught a whopping 495 million salmon – 420 million of which were pink salmon. That is more than double Alaska’s total take of 119 million.

So is Russia taking more than its fair share of salmon?

The answer is no, according to fisheries experts. Russia is taking more salmon because it’s getting more salmon back.

The NPAFC notes that Pacific salmon abundance has shifted in recent decades north and west – to Alaska and Russia – while more-southern regions (B.C., Washington and Oregon) have experienced declines.

Areas like Bristol Bay in Alaska and the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia have produced large returns of salmon (including sockeye) in recent years, while their numbers have declined in southern regions.

“Canada historically had a higher portion of the catch, but since the boom in Alaska and Russia in the late ’70s, Canada’s catch has declined and its proportion has declined a lot,” said Ray Hilborn, a fisheries researcher at the University of Washington. “Its pattern is pretty similar to lower-48 U.S. – basically too warm for southern stocks to do well.”

Combined, Russia, Alaska and Japan introduce five billion salmon – mostly pink and chum – into the Pacific Ocean each year through commercial hatcheries.

Some scientists have suggested that these hatchery fish may be at least partly responsible for the decline in sockeye, chinook and other wild stocks.

But Hilborn noted that pink salmon seem to be thriving, regardless of whether hatcheries augment their stocks.

And Beamish pointed out that Bristol Bay recorded its highest sockeye return last year, even though Alaskan hatcheries produce few sockeye.

According to the NPAFC, Alaska pumped out three times as many pink salmon hatchery fish as Russia (one million, compared with Russia’s 257,159), yet Russia has had much higher pink salmon abundance than Alaska – a record return, in fact, last year.

Japan also produces a lot of hatchery fish. But it too has seen a decline in chum salmon in recent years.

Despite adding about 1.6 million chum salmon to the Pacific Ocean each year, Japanese commercial fishermen have experienced a five-year decline in their annual commercial catch.

“It’s a common trend for the southern area,” said Vladimir Radchenko, executive director of the NPAFC. “In Japan we also have some decline of the hatchery chum salmon species last year. In 2018, it is a little bit higher than 2017. Before 2017, they have five years of continued decline.”

Were scientists wrong about hatcheries?

In the early 1970s, eminent fisheries scientists like William Ricker, Peter Larkin and Beamish concluded the Pacific Ocean had a sufficient additional carrying capacity to produce more salmon, and promoted the idea of boosting fish stocks through hatcheries.

“We told Treasury Board that by the year 2005, the Canadian catch would double, from about 65,000 tonnes to 130,000 tonnes, and by 2005 instead of 130,000 tonnes, we were about 20,000 to 25,000 tonnes,” Beamish said.

“So, it didn’t work. Adding more numbers to the ocean and expecting to get more back did not work.”

However, he added that for a time it did work for Japan, where chum salmon production increased until about 2002.

“And it’s been declining ever since,” Beamish said.

The scientists were right that the Pacific Ocean did have additional carrying capacity. That is demonstrated by the overall abundance of Pacific salmon, which has doubled since the 1970s.

“Why did the abundances from the mid-’70s to now just about double, and then you have Russia, for example, getting its highest catch in history last year?” Beamish asked. “Well, it’s mostly pink salmon.”

Odd-numbered-year pinks have done very well, and Beamish thinks they are better adapted to warming oceans than even-year pinks and other salmon species.

He is convinced that the most important phase of a salmon’s life is the first couple of weeks after it enters the ocean. If there is sufficient food in inshore waters, they will survive.

He thinks fast-growing pink salmon – especially odd-year pinks – are better adapted to survive those first couple of critical weeks than other species.

“Adding more fish to the ocean sometimes works, if there is a capacity in that near-shore environment to provide the food for them so that they can grow faster and quicker,” Beamish said. “The increase in pink salmon is largely because wild pink salmon are surviving better.”

In response to recent declines in chinook salmon, which are the main diet of southern resident killer whales, the federal government has implemented new restrictions on the sport sector.

But the drop in chinook numbers is not just a B.C. story.

“Chinook salmon are declining in abundance from Alaska to California,” Beamish said.

He pointed to a recent paper by Alaska scientists that confirms the importance of early-stage survival for chinook.

“It clearly shows that the declining survival of chinook salmon in Alaska is related to the early marine growth period,” Beamish said.

Illegal fishing and bycatch

While annual commercial catch data is an important tool for assessing salmon stocks, not all salmon that are caught are reported.

There are concerns with both illegal salmon fishing and unreported bycatch from other fisheries.

Poachers use high-seas drift nets that can be several kilometres in length and scoop up huge amounts of fish.

Last year, the U.S. Coast Guard intercepted and detained a Chinese vessel, the Run Da, fishing north of Hokkaido.

It was caught with 80 tonnes of salmon, mostly pinks, and one tonne of squid. That’s about 60,000 salmon. To put that in perspective, the entire B.C. recreational fishing sector’s take of salmon was less than 110,000 for the entire year in 2018.

“This whole issue of illegal and unregulated fishing is a big problem,” said federal Fisheries and Oceans Minister Jonathan Wilkinson.

“If you don’t know how many fish are being taken illegally, it makes it very difficult to know how many are going to come back and therefore how many you can allow commercial and recreational and First Nations fishers to catch.”

He said Canada has raised the issue with the G7.

“We’ve been working with the United States on enforcement actions, and we’re certainly having conversations with China,” Wilkinson said.

Canada is also rolling out a new space-age tool to combat illegal fishing. On June 12, SpaceX launched three new Canadian satellites into orbit as part of the Radarsat Constellation Mission.

One of the things that the new satellite observation system will be used for is to track illegal and unregulated fishing vessels.

Another major concern for fisheries managers is unreported bycatch of salmon by pelagic fisheries.

“All of them can have bycatch of salmon, and there is absolutely no statistics on this bycatch,” said the NPAFC’s Radchenko.

The commission is working with the North Pacific Fisheries Commission to enforce the reporting of unintended bycatch of salmon.