Although it doesn’t always glitter like gold, water is becoming America’s most precious commodity as utilities strengthen security and monitoring with Vancouver technical expertise.

A confluence of 9/11, natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina, droughts, growing populations, incidents of domestic and cyber terrorism and complex compliance regulations have all put the water industry on tenterhooks.

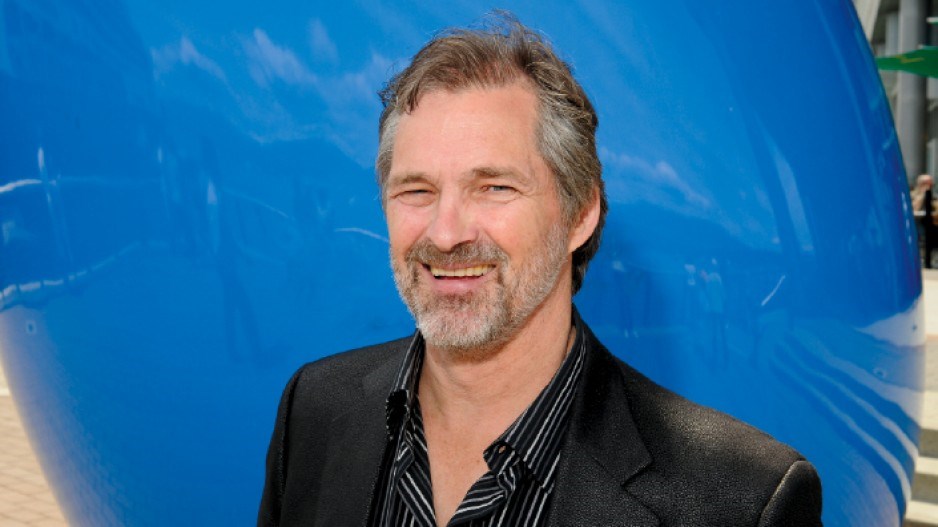

John Saunders, owner of Vancouver-based security firm Enterprise Protection Associates, provides risk and vulnerability assessments for corporations, governments and utilities. His first water-utility related job was in 2003, but that industry niche has now grown into 75% of his workload.

Most of Saunders’ consulting time is spent in the U.S., including partly parched states like California, Texas and Arizona, where his American home office is established.

“[The southwest] has survived a nine-year drought that just ended last year,” said Saunders. “The southwest is acutely aware that water is a resource that can run out and [is] willing to put in the protection that is necessary.”

Saunders, a former RCMP officer, identifies gaps between utilities’ operations and potential threats. Recommendations cover physical securities of fences and walls, electronic surveillance and access control, IT improvements, and policies and procedures.

After 9/11 and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, vulnerability assessments became required for all U.S. major drinking water systems, classified as critical infrastructure. Utilities then sought the same expertise to implement identified security shortfalls.

The American Water Works Association (AWWA) now advocates that water utilities update their assessments every five years. Owing to the drinking water crisis following Hurricane Katrina, Saunders said vulnerability assessments are now tacking on the expanded scope of emergency preparedness.

Kevin Morley, security and preparedness program manager for AWWA, added that there has been a transformational change in the industry.

“Water security is more inherently integrated into the operations of the utility, more so than it ever was 15 years ago. It’s become embedded into the conscious of utility operators.”

Potential threats extend from the Wild West to the World Wide Web. In Arizona alone in the last year, an employee who shut down parts of a Gilbert wastewater plant in an attempt to blow it up was given four years’ probation in January; while on June 24, about 600 people in Sierra Vista were asked to conserve water after vandals shot up and disabled a 165,000 gallon water tank.

Morley said the water-risk focus has shifted from foreign terrorists on U.S. soil to cyber-threats on automated operating systems used by water and wastewater plants. Any U.S. state is vulnerable to foreign or domestic hacking; it’s just a matter if their network’s “door is open or closed,” said Morley.

Added Saunders: “We know for a fact terrorists have made plays along that line in the U.S. in the past. They just haven’t been terribly successful, fortunately.”

James Griffiths, general manager of WaterTrax, said threat assessments are part of the discussion among his water utility clients. One benefit of his company’s data management software is that it allows utilities to identify water sources and operational information to help them build threat assessments. However, the main selling point of WaterTrax, which debuted in 2001, is that it provides cloud-computer-based monitoring of water quality to detect contaminants and meet growing compliance regulations.

Various monitoring stations and operations generate an enormous flow of raw data dumped in paper-based systems or Excel spreadsheets, which Griffiths said aren’t automated and are prone to human error and missing data.

In addition, water samples are sent to labs and sometimes take a week before raw data is mailed back to be interpreted.

The list of WaterTrax subscribers, an equal mix of Canadian and U.S. large water utilities and municipal governments, has doubled in the last five years to 125.

Griffiths said that one of the biggest challenges today is an increasingly complex compliance environment – the requirement to sample more often for an increasing number of chemical parameters, from traditional microbial intruders to complex pharmaceutical contaminants.

Adrianna Negreros, water quality technician for California’s Golden State Water Company, said it would take the utility several hours to compile a very simple report with certain data.

“Now it’s just a matter of a click here and there and you have all of the data in minutes. I’ve been in this industry a long time, and I know life before WaterTrax and life after. It’s just fantastic. It automatically reminds us what needs to be monitored or what’s missed and it helps us stay compliant.” •