On a recent overcast day, Emmanuel Essah-Mensah walked through his two-hectare farm in the heart of Ghana’s cacao belt.

In a normal year, he would be surrounded by a palette of green — dappled light filtered through a lush canopy, heavy cacao fruit drooping from trees. Two years of prolonged drought and a steady rise in extreme temperatures has shattered that reality.

Essah-Mensah’s farm is in the midst of the main growing season. But cacao fruits are scarce. Flowers have wilted and died in the heat. A lack of soil moisture has stunted tree growth, causing them to shed their leaves. Everything has turned brown.

Underfoot, the crunch of Essah-Mensah’s steps nearly drowns out the call of songbirds. Perhaps worse, the farmer said in an interview, across the Ashanti region, young cacao trees are experiencing an 80 per cent mortality rate.

“It’s painful,” said the farmer. “That is a whole lot of loss.”

The cacao-growing regions of Ghana support about 850,000 families. By this time of year, they should have had three or four rainfalls, and a bumper crop of cacao. But so far, no rain has fallen, said Essah-Mensah.

“We here in West Africa are absolutely feeling the impacts of climate change — severely,” he said. “It’s causing a great decline in cacao.”

From tropical farm to chocolate delicacy, cacao has fanned out across the world since it was exclusively imbibed by Aztec royalty more than five centuries ago.

Native to the Americas, the crop has flourished in plantations across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where cacao is loaded onto trucks, railcars and ships to feed a global industry worth $114 billion US.

Denman Island Chocolate Factory sits at the other end of that supply chain, more than 11,000 kilometres away in the shadows of a very different forest.

Daniel Terry and his wife founded the island factory in 1998 as the first organic chocolate company in Canada. In the decades since, Terry says chocolate prices have remained remarkably stable.

But that all changed in 2023, when drought hit West Africa. As cacao trees wilted and died, global supply dropped. By the end of 2024, cacao was being traded at a record $12,605 per ton — a 400 per cent increase from before the drought.

Terry said it doesn’t matter that only some of his cacao butter comes from West Africa. Ghana and neighbours Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon and Nigeria account for 71 per cent of global cacao production. A decline in West African cacao trebles prices across the globe.

Spiking cacao costs have forced the B.C. chocolate company to raise its prices 15 per cent, and Terry expects that to go up another 25 per cent soon.

“It’s pretty bonkers,” said Terry. “It’s just gone up and up and up.”

Researchers trace climate change footprint to cacao belt

A report released this week by the U.S. research group Climate Central has shed new light on why global chocolate prices have seen such a pronounced spike.

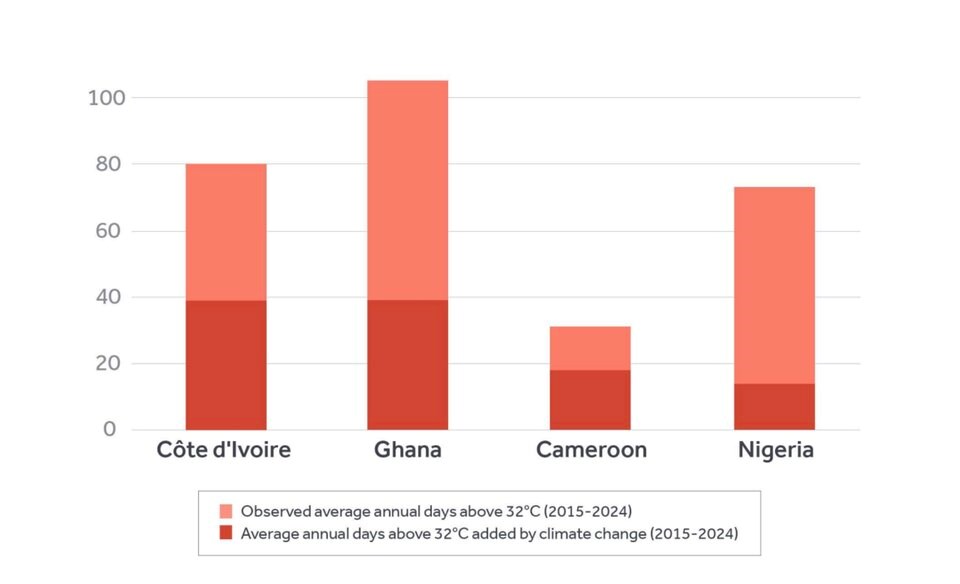

In addition to drought, the report found that over the past decade, climate change has raised temperatures above 32 C — the optimal temperature to grow cacao trees — for a total of six weeks across West Africa’s four heavyweight cacao-producing countries.

In Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, temperatures climbed past the 32 C mark three weeks longer during the October-March growing season. Cameroon saw two weeks of 32 C-plus weather added to its main crop season, while Nigeria saw more than one week at the elevated temperatures, the report found.

When Brian Kerzner founded Rocky Mountain Chocolates in Whistler 38 years ago with his wife, he never expected prices to jump past the$10,000 US-per-tonne mark, the point where everyone in the industry says “shit hits the fan.”

“Now we’re here,” said Kerzner, incredulous.

Part of the problem is due to a global labour shortage, which pushes up prices across the supply chain, he said. Add in the drought and heat hitting West Africa and prices have been spiralling.

“It’s a compounding effect all the way through,” Kerzner said. “Will that dissipate next year? In 10 years? Who knows?”

The company now has about 50 stores spanning the country, from B.C. to Newfoundland. The company’s prices have climbed about 40 per cent in the past five years, and Kerzner expects the rising cost of cacao to push them even higher.

Those in the craft chocolate-making business say the spike in cacao prices has hit their margins even harder.

'Not sustainable'

Nathan Mah and his wife bought the Vancouver business Gem Chocolates in August 2024 — in part as a legacy for their son, who has special needs, and also as a way to support the wider neuro-divergent community, which today make up a third of their staff.

But by the end of the year, their supplier — which sources raw cacao from Colombia and Belize — had increased prices by 70 per cent. That cut the couple’s margins in half.

“With West Africa going through that drought, we’ve experienced significant increases,” Mah said.

The Mahs have tried to cut costs on everything from packaging to shipping. But some costs, like rent at their Kerrisdale storefront in Vancouver, are fixed. They soon plan to raise prices.

“It’s not sustainable,” Mah said.

In Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood, Mara Mennicken took over The Good Chocolatier five years ago after learning the trade from a French chocolatier who used fair trade Ecuadorian cacao. In the years since, she never stopped sourcing cacao from 50 small farms in the country’s south.

When she entered a new contract period with her supplier in early 2024, Mennicken thought she was insulated from surging cacao prices. That spring, cacao prices for the Vancouver chocolatier almost tripled. Today, an 800-kilogram order of her Ecuadorian cacao paste costs $24,000 US, up from the previous $8,000 US, she said.

Within months, the cost to produce a bar of chocolate went up 50 per cent. That cut the company’s margins in half. Paying rent, maintaining operations and still leaving money to innovate became increasingly difficult.

“It was so scary,” Mennicken said. “In April, I really thought, I have to shut down my business. It’s not sustainable. I’m not going to sell a chocolate bar for $15 in a supermarket.”

Raising prices that much that fast could risk scaring off her customers, she worried. At the same time, Mennicken had found a way to get her chocolates into 100 retail stores, up from 35 in 2023. She was selling more chocolate than ever before but struggling to keep up.

Pressure to adapt leads to new products

Once she got over the price shock, Mennicken started looking for other ways to cut costs. Using lesser-quality ingredients wasn’t an option, nor was switching to another supplier, she said.

“I tried to find other cocoa that maybe was a cheaper price, but similar quality, and it took me four months. I didn’t find anything that was just as tasty and that also has our business values,” Mennicken said.

Instead, she looked for distributors who could sell her other non-cacao ingredients at lower prices. Then she got inventive.

Mennicken started using more raw cacao nibs, which even though they take another day in the grinder to process, are slightly cheaper. And whereas in the past, most of the chocolates she produced tended toward the dark variety, Mennicken started coming up with more milk chocolate recipes that use slightly less cacao. Still, she said, every unused piece of chocolate or broken bar now hurts a little more.

“Every single littlest piece you just start to appreciate more,” she said. “Nothing gets wasted.”

All those measures have tempered the company’s price increases and softened the impact on her customers, Mennicken said.

Global supply chain requires solutions on both sides

Back in Ghana, Essah-Mensah and his neighbouring farmers are also not giving up in the face of crisis.

To reverse the decline in cacao production, they have turned to incorporating more natural forests and other crops throughout their farms. The practice, known as agroforestry, offers a chance to grow other cash crops and vegetables to eat at home.

The idea is to plant a variety of trees that shade cacao and minimize the evaporation of soil moisture. And instead of slashing and burning forests to make way for new plantations, Essah-Mensah is part of an effort to convince his fellow farmers to take up no-till farming, which means minimal soil disturbance before planting to protect soil from high temperatures and moisture loss along with wind and water erosion.

It’s an idea backed by Josephine George Francis, a Liberian cocoa and coffee farmer who moonlights as the vice-president of the Network of Farmers’ Organisations and Agricultural Producers of West Africa.

The group — which spans 13 countries, including the region’s big four chocolate producers — has been in the Ghanian capital of Accra this week lobbying the country’s agricultural minister to back more farming co-operatives.

Bringing farmers together under co-operatives offers a chance at small loans and marketing that could give farmers an opportunity to adapt to the extreme weather, said Francis. It’s a model already popular in the region’s francophone countries but nearly absent in English-speaking countries.

“The whole region is really suffering from drought,” Francis said. “It’s going to get worse.”

For Essah-Mensah, those efforts have not proven enough to overcome the current drought and extreme heat. But as a man who grew up on a farm, and with his first child on the way, Essah-Mensah still spends his days looking for solutions that will show his kid he is a proud cacao farmer.

Part of the solution, he said, needs to happen overseas in places like Europe and North America, where few are willing to pay for the true cost of growing cacao.

“That delicious chocolate that you use to celebrate with your loved ones and your family,” added Francis,“Just imagine where it came from.”