Most of the 37 cannabis stores operating in Vancouver are not legal, though the majority could be provincially and municipally approved by year’s end.

Part of that transition involves wheeling and dealing between players, where former grey-market operators sell leases with City of Vancouver development permits to entrepreneurs who want to operate legally.

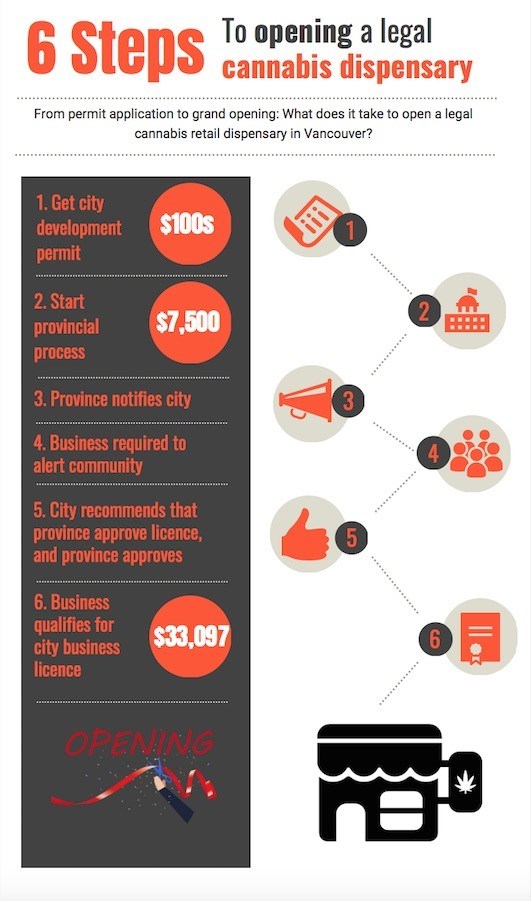

The speed of the transformation depends on how fast the province approves applications, followed by how quickly entrepreneurs can qualify and pay for city business licences, which cost $33,097 per year, pro-rated.

“What we’re seeing is a lot of grey-market operators’ reluctance to go the legal route even if they have got [city] development permits in the past,” said Donnelly Group owner Jeff Donnelly.

“We are contacting them all and being contacted by them, and we have some more opportunities to buy development permits.”

Donnelly operates legal stores under the Hobo brand at 8425 Granville Street, in the Marpole neighbourhood, and at 4296 Main Street, near East 26th Avenue.

He recently shelved plans to open stores on Nelson Street near Granville Street and on Commercial Drive near East 10th Avenue, although different owners are likely to open there.

Instead, Donnelly told Business in Vancouver that he plans to open stores in Kelowna and on West 4th Avenue.

“We’ve been switching it up a bit,” he said. “With the provincial limit being eight stores per owner, we have to decide what stores we’re going to do, and what ones we are not going to do.”

He expects that his final four stores will be in Metro Vancouver.

(Story continues below)

What is the current status of stores in Vancouver?

Six legal stores are open in Vancouver, including one at 3039 Granville Street, which was the most recent one to open. The problem with calling all other stores illegal is that there are many shades of illegality.

That is why many people were confused on May 31, when the British Columbia Court of Appeal ordered nine cannabis stores to close but not dozens of others that were operating without provincial and city licences.

Those nine stores were named in a lawsuit launched by the city last summer after the dispensaries had rejected the city’s right to regulate their presence. Owners had refused to get a business licence or a development permit.

The dispensaries wanted the Court of Appeal to set aside a December BC Supreme Court decision, which stated that they had to close because they did not have city authorization to operate. The Court of Appeal rejected the owners’ request to keep their stores open while they considered whether to appeal.

The owners remain eligible to appeal the lower court’s December decision.

The court order was effective, as seven of the nine stores closed within a week, while the other two converted into locations that do not sell cannabis. That was what the city wanted, City of Vancouver chief licence inspector Kathryn Holm told BIV.

When the city launched its petition in mid-2018, it targeted 53 stores that operated without a city development permit, which is the precursor to a city business licence. With the recent closures, none of those stores sell cannabis anymore.

There are, however, 37 stores that sell cannabis, and most are seeking provincial and city licences.

The wisest first step is to get a city development permit, which confirms that the store is in a location that the city deems appropriate.

Stores cannot be within 300 metres from another store or a school, community centre or gathering place for youth. They’re also prohibited from being on a street that the city deems to be a minor or residential road.

An applicant can pay a $7,500 provincial application fee to start the process, and then try to get a city development permit. Entrepreneurs aiming to open five stores have done that.

But Holm said the entrepreneur would be out the $7,500 if the city declined to issue a development permit for the location proposed to the province.

Holm said the city is primarily targeting owners of 10 cannabis stores that have no development permit and have not launched the licensing process with the province.

The city has filed or is preparing to take legal action against those stores in part because most, if not all, of the locations are ineligible for development permits.

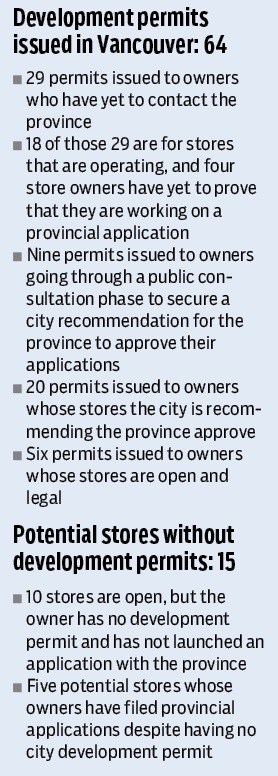

The city has issued 64 development permits to cannabis entrepreneurs, and owners of 29 of those permits have yet to launch the provincial process. That is a concern for the city in 18 instances, where the permits are being used to operate a store.

Holm said the remaining 11 permits are inactive and not being used to operate a store.

She added that four of the 18 development-permit owners that are operating stores “are not demonstrating a commitment” toward going through the provincial process, and she named a dispensary at 1182 Thurlow Street as an example.

Cannabis activist Dana Larsen is a director involved with the society that runs that store. He told BIV that the society plans to get the store provincially licensed.

Of the 35 proposed stores where owners have development permits or city approval for the location and have started the provincial process, the city has recommended that the province approve 26.

Owners of six of those stores have completed the process, bought business licences and are open. Provincial bureaucrats are studying applications for the other 20 stores and conducting security checks.

“Retailers operating illegally will not be disqualified from applying for a licence,” the Ministry of the Attorney General said in a June 11 statement to BIV.

It added that those applicants are also eligible to be granted permits. •