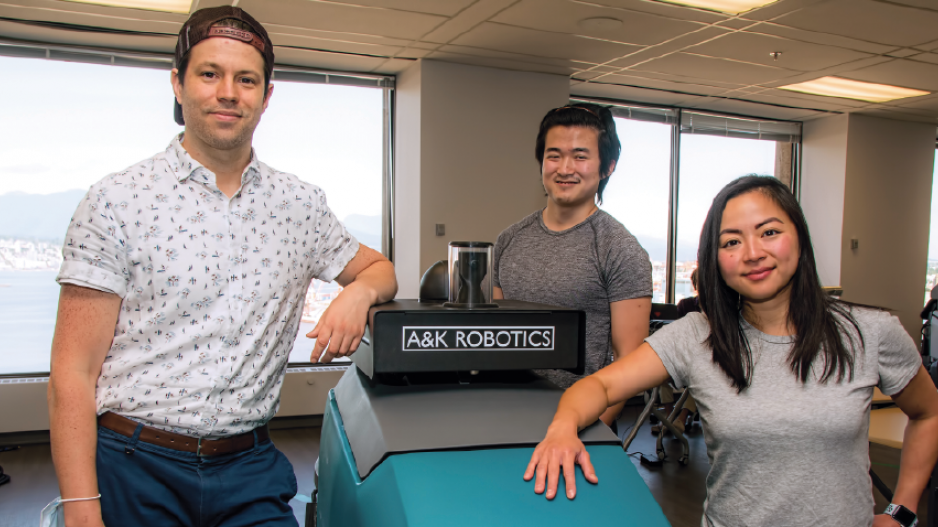

With a line of janitorial robots already commercialized and scrubbing floors three years ago, A&K Robotics Inc. had turned its intention to developing a disinfecting prototype robot.

“The problem was back in 2017, nobody wanted to pay for a robot that would clean what’s invisible to us,” recalled Matt Anderson, CEO and co-founder of the Vancouver-based robotics firm. “So we shelved it, and it’s basically been collecting dust ever since.”

But the COVID-19 crisis upended that, prompting the company to revive the prototype known as AMRUD with financial backing from the Ontario-based Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster.

“We’ve had this shift recently from cleaning for visual appearance to cleaning for public health,” Anderson said. “Now as a result of that, people understand the importance of disinfecting, especially in health-care environments.”

Equipped with wheels and a robotic arm, AMRUD is essentially a miniature self-driving vehicle that disinfects using low-powered UV lights capable of getting within centimetres of surfaces to clean them.

One array of lights targets floors, while fellow Vancouver tech firm Sanctuary AI has partnered on the project to help develop the arm that uses UV lights to disinfect high-touch surfaces like door knobs.

The supercluster, which the federal government funds, is distributing $5 million to five projects across Canada that are addressing the pandemic through robotics.

A second West Coast project led by Advanced Intelligent Systems Inc. (AIS) has also been tapped for supercluster funding. It plans to initially deploy its disinfecting robots to hospitals such as Vancouver General Hospital and labs at the University of British Columbia.

Other facilities like shopping malls and manufacturing plants could follow, according to CEO Afshin Doust.

Doust added that AIS is working with a manufacturing partner in Canada to produce the robots.

AIS got its start in 2014 trying to address labour shortage issues at horticultural nurseries through autonomous machinery, but it has since been branching out into agriculture.

The company has already developed the hardware and software necessary for robots to navigate locations and perform tasks, allowing it to deploy the UV-disinfecting robots relatively quickly into the pandemic.

“We said let’s create modules – robotic modules – and let’s use this module to help other companies lower their development time and development costs of creating new robots,” Doust said.

“People started reaching out to us to say, ‘Hey, can we use your robots in order to create UV-disinfecting robots out of them?’ And we said, ‘Yes, we do have the modules.’”

The only thing that needed to be added were the UV lights.

A&K, meanwhile, hopes to begin deploying its robots next year at Canadian transportation hubs and hospitals.

Both companies use the business model centred on “robot as a service” (RaaS) – a take on SaaS (software as a service) – allowing companies to rent the machines instead of investing significant amounts of capital all at once.

Customers pay $10,000 for 1,000 hours’ use of A&K’s janitorial robots. For the AMRUD robots, Anderson expects clients will be charged an up-front cost plus a subscription RaaS fee.

Doust said the pandemic has accelerated business plans already in the works prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

“What I see for AIS in the future is we’ll probably be pivoting into creating a lot more robots for different verticals, and we’ll also be using our modules to allow our colleagues in other robotic companies to be able to produce robots faster and at a cheaper price.”

Anderson, meanwhile, said the country still lags behind many European states, China and Japan in embracing robotics.

“It’s very exciting that Vancouver and Canada is really realizing the potential of automation to support our frontline workers. We are hoping that us and the other robotics groups in Canada will be able to keep Canada at the forefront of technologies like this.”