Living among the stars, astronauts crave a taste of home.

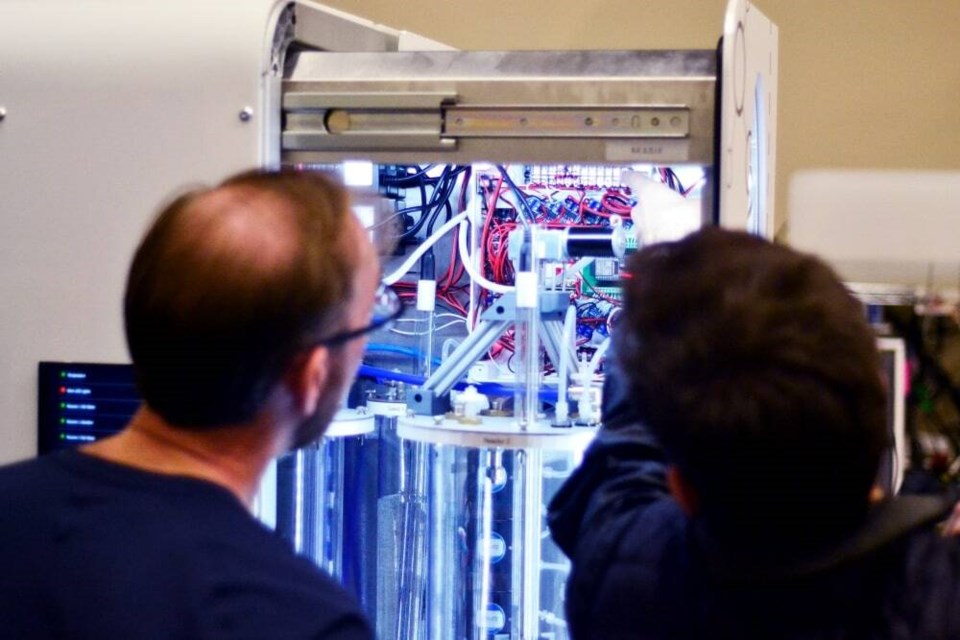

Juicy tomatoes, sweet strawberries, fresh lettuce and a meaty, mushroom-based protein can all be grown in a two-cubic-metre box, a system called CANGrow, which has just won its creators a $380,000 grand prize in a national space food contest.

Over the past year and a half, a North Vancouver team with members from Ecoation Innovative Solutions and Maia Farms have competed against 70 applicants across Canada, which whittled down to four finalists last April, to win the Deep Space Food Challenge.

The national contest has been furnished and judged by the Canadian Space Agency, and has an American counterpart running concurrently south of the border, run by NASA.

The CANGrow team has demonstrated the ability to build some extremely sophisticated technology that could have an impact on the future of space travel and the ability for humanity to populate other planets, explained the project’s head farmer, Gavin Schneider, who’s also CEO of Maia Farms.

But the judges first really wanted to see that the technology could have an impact on earth, he added.

“One of the things that we’re looking at for the commercialization of this is deploying it in remote northern communities,” Schneider said. “[Places with] a lot of food insecurity, an inability to access fresh produce.”

Existing alternatives like container farms are often too big, too expensive and too difficult for one person to manage, he said. And greenhouses have seasonal restrictions.

“We wanted to [build] something that a single person could operate, with as minimal labour required to be able to produce the largest amount of food,” Schneider said. “And this is what we were able to do.”

Inside CANGrow’s separate drawers are environments optimized for growing different crops – tomatoes, strawberries and lettuce in the current version. An array of sensors monitor the plants, and alert the operator of any tasks that need to be done.

A separate module on the side of the unit is outfitted with “bioreactors,” where mycelium – the network of threads that make up fungi – is grown via fermentation. In this case, the mycelium is a special variety that provides a hearty protein source, rich in amino acids and other key nutrients.

With some basic training, an operator can produce a protein harvest every seven days and fresh lettuce every 20 days. Tomatoes take 55 days from seed to first fruit, while strawberries can take nine to 12 months to grow a plant from seed, but will continue to produce berries after that.

Overall, the system can produce around 700 kilograms of food per year, Schneider said, with the aim of supplementing the diet of around four people, in addition to other food sources like carbohydrates.

Simple-to-run system provides nutrition as well as psychological benefits, creator says

Also important to CANGrow are its relatively simple inputs.

“The only thing that this unit requires is 120-volt power, and a garden hose hooked up to be able to run, which is very unique for this type of system,” Schneider said.

The system recirculates all of its water and is outfitted with a composting unit to minimize waste, he said.

Following the Space Food Challenge victory, the prize money is being distributed among the 15-member team, who have effectively been leading double lives throughout the competition, Schneider said.

Next, the CANGrow team will focus on building new iterations of the unit, and work toward delivering other commercial applications for the technology.

“We’ve had interest from cruise ships, we’ve had interest from mining communities, where they have crews of people flying in, but shipping all of that produce is very expensive,” he said. "They also don’t want to operate a greenhouse on site.”

But Scheider is also looking to new frontiers, where his farming units could help extraterrestrial explorers thrive in alien environments.

“There’s also a psychological aspect to this is: I want to touch a green plant because it’s familiar, reminds you of home,” he said. “The colour and smell is a big part.

“When we had this full of tomatoes, you’d open it up and it was just this overpowering sensation of fresh tomatoes. And this was the middle of January in a warehouse in rainy North Vancouver,” Schneider said. “There’s that benefit to it as well beyond just the nutritional aspect.”