On a recent sunny Friday afternoon, the reception desk of B.C.'s biggest timber company appears to be abandoned.

Not so, assures the company's CEO: there simply is no receptionist. Then he rushes off to fetch a glass of water for his visitor. Welcome to the offices of West Fraser Timber (TSX:WFT), whose modest ambience belies its current position atop B.C.'s lumber world. The company now edges out its better-known rival, Canfor (TSX:CFP), in both earnings and number of employees worldwide.

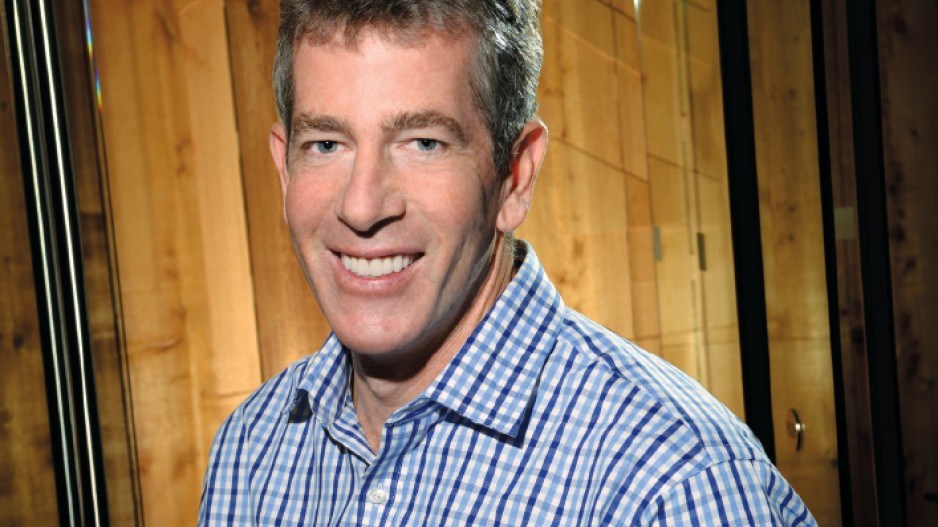

"Analysts say our share performance over the past 30 years has outperformed all our competitors and significantly outperformed both the TSX and the NYSE," boasts CEO Ted Seraphim.

Seraphim, 53, took over the role in March 2013 after stints as COO and vice-president of West Fraser's pulp division.

His career, he says, is an example of what has made the company successful. Like many of its employees, Seraphim has been at the company for more than two decades. Hank Ketcham, the previous CEO and son of one of West Fraser's founders, led the company from 1985 to 2013.

"We've only had a few CEOs and we've only had three senior management groups," said Seraphim.

The company prides itself on developing its talent from within rather than looking elsewhere.

"We had more than one strong internal candidate," said Ketcham. "We didn't have to look outside the company at all."

Ketcham described Seraphim as "very, very smart."

"He's got a great strategic mind … and he's got very strong leadership skills."

Most importantly, Seraphim's values fit the company culture, and he had the unwavering backing of the senior management team, said Ketcham.

One more thing: "He's very competitive."

That competitiveness might not be apparent at first. Seraphim speaks a lot about teamwork, company values and the general "low-key" atmosphere of the company.

But on the subject of West Fraser's competitors, it's clear that he sees his company as the leader, both in strategy and results.

"[Canfor and Interfor] are looking to our business model, and they see value there," he said. "We're going to have more competition for growth from not just those companies, but U.S. companies."

While 55 employees work out of the head office in Vancouver, Seraphim described West Fraser's Quesnel operations office as "the heart" of the company, with more than 100 people based there. The company was founded in Quesnel in 1951. It now has more than 7,000 employees throughout North America.

The company's executive team stays close to what makes the business tick by visiting its mills many times a year.

In an industry where all the players are trying to be low-cost producers of the same product, West Fraser strives to have the lowest costs of them all. That frugality means going without a receptionist and cleaning up the lunchroom, even if you're the CEO.

But it has also meant spending, as long as it's in the right places, like growing where the timber supply is strong or investing in new equipment that speeds production.

Seraphim grew up in Vancouver and trained as a chartered accountant at UBC, although he knew at the time that being a CA wasn't what he ultimately wanted to do. His mother was a schoolteacher; his father worked as a salesman for business equipment maker Olivetti.

"My mother had a university education and my dad didn't, and he really drove his children to go to university. He drove me to also have a profession."

Seraphim got his start in the forestry business when he took a job selling pulp for Fletcher Challenge. The job suited him, he said, because he likes working with people in a hands-on role. Sales also involved a lot of international travel – something that seemed glamorous at first but started to wear thin as his young family grew.

Back then, West Fraser was not a big-name company like Fletcher Challenge. But the smaller business company culture appealed to him.

"It's a company that's focused on doing things that are right for the long-term business decisions we make and, frankly, how people are thought of," he said.

For much of its history, West Fraser grew slowly by making small acquisitions.

Then came the International Paper (IP) deals in the mid-2000s. In 2004, West Fraser acquired IP's Weldwood of Canada. Weldwood's assets included a paper mill and several sawmills in B.C. and Alberta.

"Ten years ago, the mountain pine beetle was with us in a very big way, as it is today, and we knew that the industry in B.C. was going to get smaller," said Seraphim. "So we thought the best way we could manage that was to grow here."

In 2006, West Fraser became a major player in the U.S. when it bought 13 IP sawmills ranging from Texas to North Carolina and began the trend of B.C. forestry companies acquiring sawmills in the U.S. south. Canfor and most recently Interfor followed West Fraser's lead with acquisitions in the Carolinas and Georgia.

While the lumber industry is used to up-and-down cycles, what happened from 2006 to 2011 dwarfed any previous market dip. The U.S. housing crash and subsequent financial crisis brought B.C.'s forestry industry to its knees.

West Fraser closed three B.C. mills: the Eurocan pulp mill in Kitimat, the Skeena sawmill in Terrace and the Northstar Lumber mill in Quesnel. Together, they employed 700 people.

The company also had to delay making badly needed improvements to the sawmills it had just bought in the U.S. south.

Now that lumber markets have finally started to rebound, West Fraser is again looking to grow – but not in beetle-ravaged B.C. The company has repositioned itself for a shrinking industry in this province.

Instead, West Fraser plans to keep acquiring assets in Alberta and the U.S. and focus on new opportunities like the bioenergy facilities it has added to many of its sawmills.

Seraphim sounds almost rueful about the market upturn because it means there aren't as many opportunities for the company to buy more mills.

"Growth is going to be a bit of a challenge for us for the next few years, but with every upturn there will be a downturn," he said. "We want to make sure we're positioning ourselves for the downturn."