To many Vancouver residents, a train running through Kitsilano, Kerrisdale or Marpole is unimaginable. The Arbutus corridor has become a pleasant place to stroll or bike, with community gardens proliferating alongside the overgrown railroad tracks.

But while the corridor is currently park-like, transportation is in its near and long-term future.

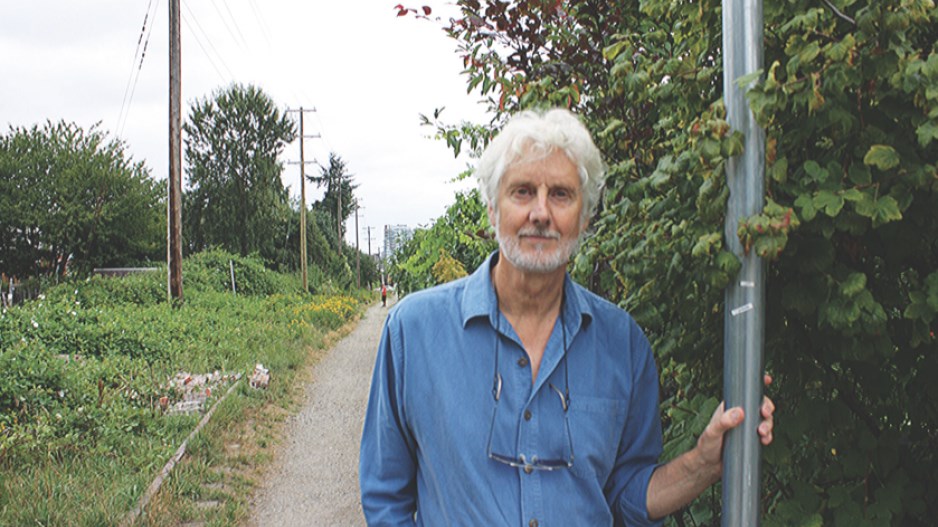

“It's still really valuable as a corridor,” said author Michael Kluckner, who has written several books about Vancouver's history.

“It's all caught up in the heat and the fury over whether people can have gardens there or whether people can walk their dogs there. But strategically, from a planning point of view, that part of the city will inevitably grow.”

Earlier this month, the owner of the right-of-way, Canadian Pacific Railway (TSX:CP), started destroying the community gardens that have sprouted up along the line over the past 14 years. The company says it wants to restore the track to operational use and will likely use it for training and storage. The line was last used for freight in 2001.

The move comes as part of a long-running dispute between CP and the City of Vancouver over the fate of the 11-kilometre stretch of track. CP would like to ultimately sell or develop the land; the city wants to retain the land in its currently zoned use as a transportation corridor.

To stop using the land for a railway, CP “must go through a process of decommissioning the line,” Douglas Harris, a law professor at the University of British Columbia, told Business in Vancouver in an email.

“But once completed it could use the land for non-railway purposes if the zoning allowed it.”

In 2006, the city won a lawsuit affirming it had the right to zone the land.

It's very unlikely CP is seriously considering rehabilitating the line to regularly run freight cars along it, said Peter Hall, a professor of urban studies at Simon Fraser University. The track no longer connects to the False Creek Flats rail yards because of land sales CP has made in the past, and buying and permitting land to do that would be difficult and expensive.

“There's one vague, in-the-distance scenario that says this is a third way of having rail access to False Creek Flats,” Hall said.

“It's not possible at the moment – they would need to fill in the missing pieces – but it's not absolutely impossible.”

Hall argues a case could be made that rehabilitating the line for freight would benefit the Metro Vancouver region as a whole because it would reduce pollution and congestion by taking trucks off the roads.

But the more realistic scenario, Hall said, is that the city will eventually get control of the land and, at some point in the future, use it for transportation such as light rail.

In a July 16 letter to Vancouver residents, Mayor Gregor Robertson wrote he believes the corridor “should remain as it is today – an enjoyable route for people to walk, run and bike along.”

The city's official development plan for the corridor, completed in 2000, envisions a mix of cycling, walking, green space and either a streetcar or light rail line.

That would return the line to one of its original uses, points out Kluckner: from 1905 to 1954, the track was part of the region's interurban commuter rail system.

But keeping the land as a transportation corridor means planning for more density along the route, both Kluckner and Hall said. There has been pushback to public transit in the past from residents, leading to elevated rail like SkyTrain being excluded from the 2000 development plan.

“Somewhere along the line the city has to commit itself to using the land at either end and at specific points along the corridor more intensively than it's using it at the moment,” Hall said. “If it doesn't want to use that land for industry … that's not ideal, but please let's replace it with some higher-density residential areas.”