Wednesday morning in Metro Vancouver. The rush hour is in full swing. Luckily, it's not raining and, for the most part, the commute goes smoothly. But there are trouble spots: traffic crawls across the Alex Fraser Bridge and along parts of Lougheed Highway in Burnaby and the Queensborough Connector.

Commercial-Broadway Station is the usual bottleneck. Long lines of students wait for the B-line express bus, while above them on platform 3, downtown-bound people crowd onto train after train, the constant stream of arriving trains never seeming to make much of a dent in the hordes of waiting passengers.

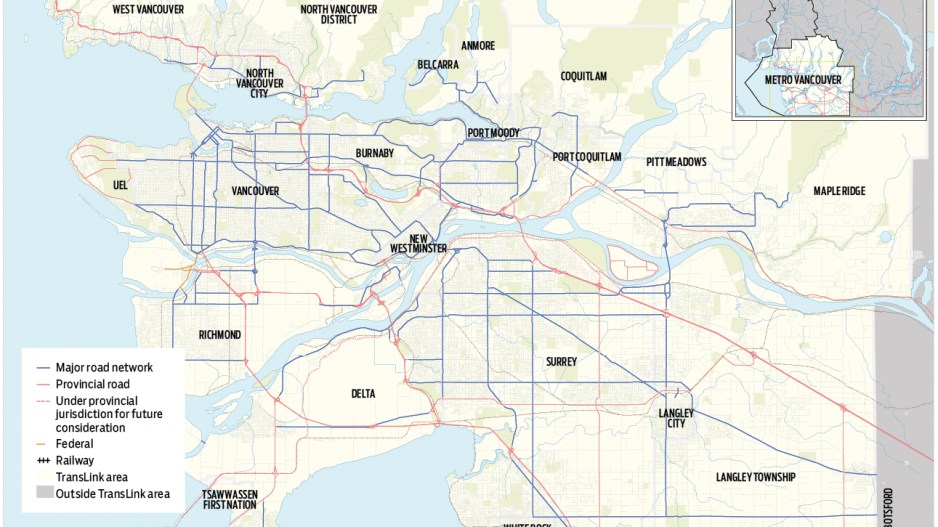

No matter if you drive, take the B-line, SkyTrain or WestCoast Express, ride your bike or walk, your commute will almost certainly put you in contact with the vast transportation infrastructure TransLink is responsible for. Roads, bridges, rail lines and several separate bus systems, as well as services like HandyDART and AirCare, all fall under TransLink's purview.

The TransLink model – a regional agency tied to Metro Vancouver's municipal political system – differs from the more fragmented approach of other major Canadian cities. For instance, Toronto has Metrolinx, a regional agency that's responsible for transit planning throughout the Greater Toronto Area, but the Toronto Transit Commission is responsible for transit within the city of Toronto, and Metrolinx has no connection to municipalities.

Proponents of the TransLink system, including Gordon Price, a former Vancouver city councillor and program director of Simon Fraser University's city program, say it works well, to the point that some other cities have copied it.

But during a decade in which decision-making was removed from municipal politicians, TransLink's brand was tarnished by rancour between the province and the municipalities, and a failure to agree on a stable funding source. That has left the large, bureaucratic agency largely leaderless and open to attack, Price said.

"We've got this idea now, this general meme, that we've got this transit system that's been improperly managed," Price said. "That is simply not true. By the standards of transit systems, externally measured, we've got a pretty good system."

But that system is increasingly under strain. Over the past several years, the mayors have ruled out raising property taxes; the province has nixed a vehicle levy and the TransLink commissioner rejected a fare increase in 2012. In 2012 and 2013, TransLink put on hold several planned improvements to the system because of the funding stalemate. Metro Vancouver's population is expected to grow by 1.4 million people by 2041, but the funding shortfall means TransLink is not increasing bus service hours to meet current demand. The theme of its 2013 Strategic Plan is "managing in tough times." •

First created in 1999, TransLink has so far operated under two governance models, each with its own problems. A third version, set in motion by Transportation Minister Todd Stone this February, is now set to shake up the transit authority once more.

1999-2008: TransLink is governed by a board made up of Metro Vancouver municipal politicians.

2008: Claiming the board was dysfunctional, Kevin Falcon, minister of transportation at the time, removes most governance power from municipal politicians and places it with an appointed board.

Mayors from the 21 municipalities that are part of TransLink sit on a mayors' council, which has the power to approve or reject tax increases and appoint members of the board.

What results, critics charge, is a transit authority with huge responsibilities but with little political will or authority to raise revenue.

2014: Transportation Minister Todd Stone puts the mayors back in charge: TransLink's mayors' council will now approve the transportation authority's 30-year regional transportation strategy and 10-year investment plan, and have authority over fare increases, the sale of major assets and TransLink's complaint process.

In return, Stone expects the mayors to become involved in the referendum campaign, including coming up with a referendum question and, by June 2014, a "regional transportation vision" that includes priorities and costs.

TransLink's appointed board will continue to exist but will make operational decisions only

Vehicle levy: Vehicle levies are proposed but rejected in 2001 and in 2012

Property tax: In 2012, the mayors' council votes to rescind a temporary increase in property tax, which would have applied in 2013 and 2014, when they and the province can't agree on a new long-term revenue source

Gas tax: TransLink's share of B.C.'s fuel tax was boosted from 15 cents to 17 cents a litre in 2012, but revenue from the tax is falling as British Columbians drive less and fuel efficiency improves

Road pricing: Extending tolls to cover more roads and bridges is supported by TransLink and the mayors' council as a way to raise revenue and manage congestion, but it's expected to be a tough sell to the public

Fare increase: A supplemental fare increase in 2013 was rejected by the TransLink Commissioner

Regional sales tax: Proposed: 0.1% sales tax

Regional carbon tax: Proposed: $2.80 per tonne

Land value capture: Proposed: develop a mechanism to capture some of the land value increases created by improved transit infrastructure

Read the rest of BIV's series on transit and the economy:

Road congestion costing B.C.'s economy billions in lost productivity and stalled job growth

The future of Lower Mainland transit improvements depends on where infrastructure funding comes from and where it will deliver the greatest benefits

Transit at the crossroads

While major infrastructure projects catering to automobiles get the go-ahead, politicians have shunted funding of buses and trains to the slow track

Bus stops versus transit metro mega-projects starts

Region faces choice: grand plans or down-to-earth service improvements?