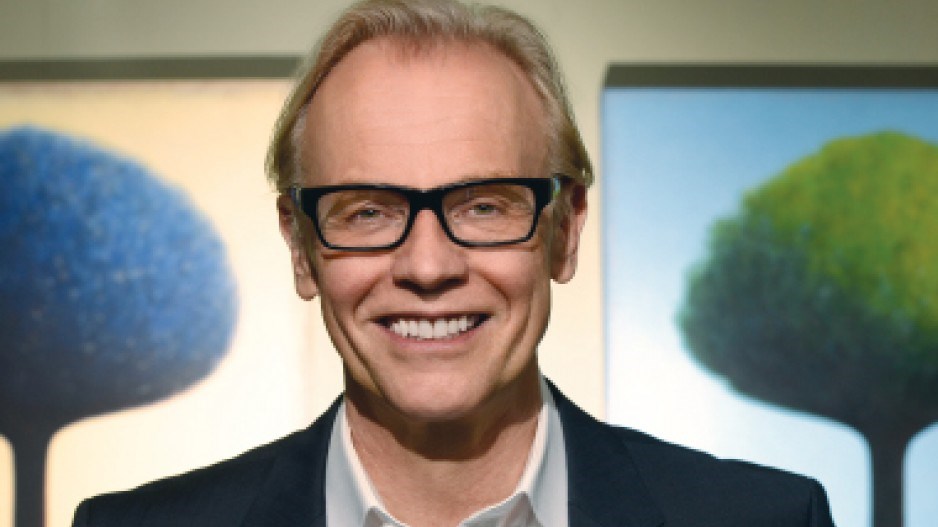

Wal van Lierop was at a CERAWeek energy conference chatting with Bill Gates about nuclear power (Gates is investing in fission, van Lierop in fusion) when the chairman of Kuwait Petroleum Corp. interrupted them.

It wasn't Gates he wanted to meet – it was van Lierop.

"He ignores Bill, looks at my nameplate, and said, 'Wal! Finally I get to meet you!'" van Lierop recounts.

Kuwait Petroleum is one of 20 global blue-chip companies that have invested through van Lierop's venture capital firm, Chrysalix Energy Venture Capital.

One of the few "pure-play" clean-tech venture capital firms in the world, Chrysalix has $300 million invested in clean-tech companies in North America – four of them based in B.C.

It recently expanded its reach with the formation of the Chrysalix Global Network, with affiliates in the Netherlands – van Lierop's birthplace – and Beijing.

At a time when venture capital investment has been in decline in general, and in particular in the clean-tech sector, Chrysalix has been playing an important role in helping new clean-tech companies get off the ground – particularly the pure-play companies, which focus on clean energy production and use. It was named the world's most active pure-play clean-tech VC in 2010 and 2011.

"Wal is an internationally connected business guy," said Jonathan Rhone, CEO of Axine Water Technologies, one of four Vancouver companies in the Chrysalix portfolio, and former CEO of Nexterra Systems Corp.

"When you're commercializing new technology, the critical thing is to find large corporates that have significant pain points these new technologies can address.

"So having an early partnership with one of these multinationals that have a pain point can be an incredibly valuable proof of validation for the technology."

Axine is a good example of new clean technology that is being driven by industries like mining and oil and gas. Its core technology is electrolytic cells, similar to those developed by Ballard Power Systems (TSX:BLD) for hydrogen fuel cells, to eliminate certain toxic compounds in wastewater.

"We see an enormous opportunity bringing the clean-tech entrepreneurs here [and] linking them up with traditional industries that really need the innovation in order for them to remain Fortune 500 companies," van Lierop said.

And that's why, when Chrysalix was looking to expand, it chose Calgary, not Silicon Valley, to open a new office.

"Every other week, we are in Silicon Valley," van Lierop said. "My colleagues in Silicon Valley said, 'Why Calgary?' I said, 'If I stay here, I will be tempted to do yet another smart meter deal, and for the next seven years we'll work ourselves through regulation and maybe by 2023 we'll get a little bit of a return. And the environmental impact? Hardly anything.'"

While some of the biggest demand for clean-tech comes from Canadian industries, there is little venture capital here. Only 10% of the venture capital invested through Chrysalix comes from Canada. Most comes from major global players, like Royal Dutch Shell and Credit Suisse – largely thanks to van Lierop's international connections.

Born and raised in Hillegom, a small town in Holland's tulip district, van Lierop studied economics and econometrics at Vrije University of Amsterdam, earning a master's and a PhD.

He became an assistant professor, then an associate professor, and consulted for the European Economic Community and World Bank, and for two years was commissioned to the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Vienna, working with scientists from Eastern Europe.

"Every third scientist from the East was a spy," van Lierop said. "When you lifted the phone, you heard a high beep followed by a low clack. The high beep was the CIA, the low clack was the KGB."

While a professor, van Lierop was among a group of academics who toured Canadian and American universities. It was in Vancouver, at a University of British Columbia lecture, that he met Nicki Stieda, a Canadian concert violinist whom he married after a two-year long-distance relationship.

Stieda joined van Lierop in Amsterdam when she was got a chance to study under the concertmaster of the Royal Dutch Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1980.

In 1988, van Lierop was tenured, but walked away from the academic life for the world of business. He joined McKinsey and Co., where he spent eight years advising top energy and chemical firms. One of his jobs was reorganizing Royal Dutch Shell's head office in London in the early '90s.

In 1995, van Lierop's wife decided she wanted to return to Canada to raise their two children, so they moved to Vancouver, where van Lierop took a position as vice-president of strategy for Westcoast Energy Inc.

Westcoast had a venture capital arm, and in 2001, when it was acquired by Duke Energy Corp. (NYSE:DUK), van Lierop got the backing of both Duke and Westcoast to take the venture capital arm private. He started Chrysalix with $10 million in funds.

In addition to Duke and Westcoast, Ballard – then an $18 billion company – was one of the original investors.

Van Lierop had little experience in commercial venture capital, so he partnered with Mike Brown – Chrysalix's chairman – who had a successful track record with Ventures West Capital Ltd.

One of the new firm's first investments was in Vancouver's H2Gen Innovations Inc. which was acquired by the French multinational Air Liquide in 2009.Another profitable investment for Chrysalix proved not so profitable for other shareholders. Chrysalix invested in Day4 Energy, which made photovoltaic (PV) cells for the solar power industry. It went public in the midst of a renewable energy bubble.

"There was a month where three solar companies got more than $1 billion in venture capital financing," van Lierop said. "That is when I said, 'we're out of here.'"

Chrysalix sold its shares in Day4, which folded last year, along with several other PV makers. Van Lierop likens what happened to PV makers such as Day4 to the early automobile industry.

"One hundred years ago, in North America, there were 100 automotive companies. Now there are three, maybe three and a quarter – I give a quarter to Tesla [Motors Inc.] (Nasdaq:TSLA). When we go to a car museum, we look at Bugatis and we drool. But the company went bankrupt.

"Day4 was a good company, as was Solyndra, as was MiaSole and many other solar companies. All these companies have resulted in costs reaching a level where now, in many places in the world, consumers are laughing because solar has become valuable at prices below the grid prices."

It typically takes eight or nine years for investors to exit a clean-tech company, so clean-tech VCs need equal measures of patience and daring. Perhaps the most daring investment Chrysalix has made is in Burnaby-based General Fusion, which is building a $70 million prototype fusion reactor.

Fusion's principal fuel supply is deuterium and lithium, both found in abundance in seawater.

"It's truly the Holy Grail of clean energy," van Lierop said.

Chrysalix is part of a VC syndicate investing in General Fusion that includes Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon (Nasdaq:AMZN).

In addition to co-founding Chrysalix, van Lierop founded the New Ventures BC competiton, which each year awards $300,000 in prizes to promising B.C. high-tech companies. Past winners include Vineyard Networks, acquired by Procera Networks for $28 million in 2009.

Venture capital investment has been in a general decline since 2009 and has been especially scarce in Canada. The biotech and clean-tech industries in particular have been hit very hard.

"That is extremely scary," van Lierop said. "The government and large companies should double up. Put more money in venture capital. Some of it may be lost. But there will be very significant winners, and the implications in your wider industry could be gigantic. We need to do this."

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)