With wildfires threatening wine-growing regions, average global temperatures rising and temperature volatility reportedly stunting production from affected grape vines, it’s no wonder winemakers fear climate change.

As part of this year’s 42nd annual Vancouver International Wine Festival (VIWF), which launches February 22 for an eight-day run, wine industry insiders from 15 countries will join scientists and others at a February 26 symposium on how climate change is affecting wine production.

French wine writer Andrew Jefford at a separate event is set to give a keynote speech on climate change uncertainties and how vineyard change has been a constant through history.

“A pressing news item in the wine industry is concern over climate change,” the festival’s executive director, Harry Hertscheg, told Business in Vancouver. “We thought we’d want to capture that with topics that are of interest to people who buy and sell wine.”

Preparing for climate change can be expensive for winery owners if they decide to rip out old vines and plant different grape varietals that are better able to withstand warmer temperatures, he said.

Many are doing this, however, and regulators in France’s Bordeaux region last year added seven grape varietals to the list that vineyard owners can plant.

(Image: Vancouver International Wine Festival executive director Harry Hertscheg wears a French beret in honour of France being the theme of this year's festival. French wine regions are allowing a wider range of grape varieties to be grown as a response to climate change | Chung Chow)

Studies have warned that swapping grape varietals may be necessary.

According to a University of British Columbia study released earlier this year, “half of current global wine-growing regions would become climatically unsuitable for today’s major wine grapes” if temperatures were to rise by more than two degrees.

“Substituting Grenache or Cabernet Sauvignon for Pinot Noir, planting Trebbiano where Riesling is grown – these aren’t painless shifts to make, but they can ease winegrowers’ transition to a new and warmer world,” said the study’s senior author, Elizabeth Wolkovich.

But Michelle Bouffard, who is moderating the VIWF symposium, said that it is not clear that cooler wine regions, such as the Okanagan, will benefit from climate change because a larger area will be suitable for growing grapes.

“It’s not just temperature change,” she said. “It’s the extreme of temperature, whether it is drought, hail, frost or freezing.”

Warmer and longer summers could make it easier for Okanagan wineries to produce excellent Cabernet Sauvignon wine, she said, but climate change may delay spring.

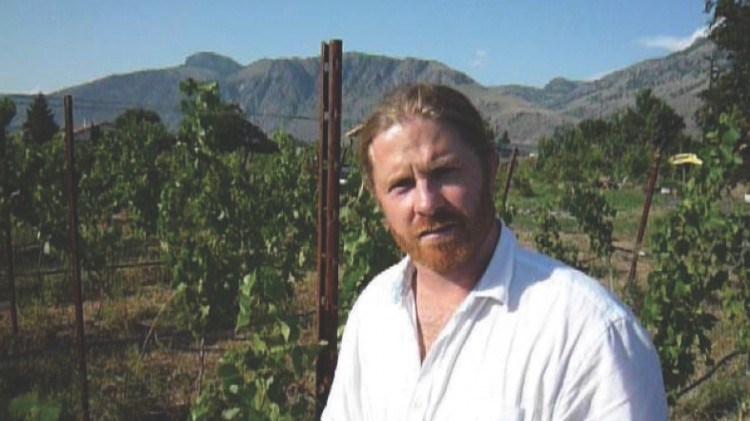

Little Farm Winery principal Rhys Pender agreed. He told BIV that in 2019 his Similkameen Valley vineyard experienced an unseasonably warm January only to face a colder-than-average February, which shocked the vines and made them less productive last year.

(Image: Little Farm principal Rhys Pender experienced reduced production last year, after a warmer than average January and a cooler than average February | BIV Files/Gordon Hamilton)

Hail is increasingly a concern in wine regions in France and Argentina, Bouffard said, adding that winemakers are adding nets above vines, and that this sometimes has the adverse effect of blocking sunlight.

The Okanagan Valley’s biggest risk, however, is fire.

Forest fires ravaged the valley in 2003, and many blazes have broken out near wineries in the years since.

Painted Rock Estate Winery owner John Skinner remembers 2015 having such an early spring that he was confident that his Cabernet Sauvignon grapes would fully ripen by the end of the year.

Fire and smoke was close enough to his Skaha Bench vineyards that his Bordeaux-based consultant, Alain Sutre, told him to keep his staff from cutting leaves off vines, as they had done the year before, when it was not as early a spring.

(Image: Painted Rock owner John Skinner enjoys some wine in his barrel room | Painted Rocki/Jon Adrian Photography)

The leaves in 2015 then provided protection from particles in the air that may have contributed to smoke taint, Skinner explained.

Ray Signorello considers himself lucky that his crew picked his Signorello Estate winery’s grapes on October 1, 2017 – one week before fire burned his winery buildings to the ground.

“It was luck,” said Signorello, who maintains homes in West Vancouver and in the Napa Valley, where his winery is located. “Our wine was made and in stainless steel vats so smoke was immaterial to it.”

Insurance enabled him to spend more than US$10 million to rebuild his winery entirely of steel, concrete and other fire-resistant materials.

He also now has the capacity to store 60,000 gallons of water that can connect to large pumps and fire hoses – something he did not have before.

(Image: A rendering of part of Signorello Estate's new winery complex | Signorello Estate)

Signorello’s winery is in a cooler part of Napa Valley so he doubts that slightly warmer average temperatures would hurt his wines’ quality.

“In my lifetime I’m not worried about it but, theoretically, things are getting worse and worse,” said Signorello, who has been a regular attendee at VIWF going back to the 1980s.

“People might have worse things to worry about than the effect on wine.”