Recent tax audits of the B.C. real estate sector are now resulting in average assessments of more than $200,000, as the Canada Revenue Agency sharpens its aim at some of the most egregious instances of tax avoidance and evasion.

“The average amount of money the CRA is assessing per file in British Columbia has increased due to our additional efforts to crack down on tax evasion” since launching an augmented non-compliance program for B.C. and Ontario real estate in 2015, CRA spokesperson Alexandre Igolkine told Glacier Media, via email last week.

The 539 B.C. audit assessments conducted between January and March this year average $208,163, for a total of $112.2 million. By comparison, the 2,565 Ontario audits in the same three months have resulted in an average assessment of only $22,261.

The 2019 audits show an uptick in penalties for knowingly making false statements on returns – which can lead to criminal prosecution for tax evasion. However, no charges have been laid.

Steven Flynn, a chartered professional accountant who specializes in international taxation with Andersen Tax, said the results don’t surprise him, “because of the rapid increase in real estate prices and what’s been well-publicized activity, what with the flipping of properties and non-compliance and illegal activity that’s gone on in B.C.”

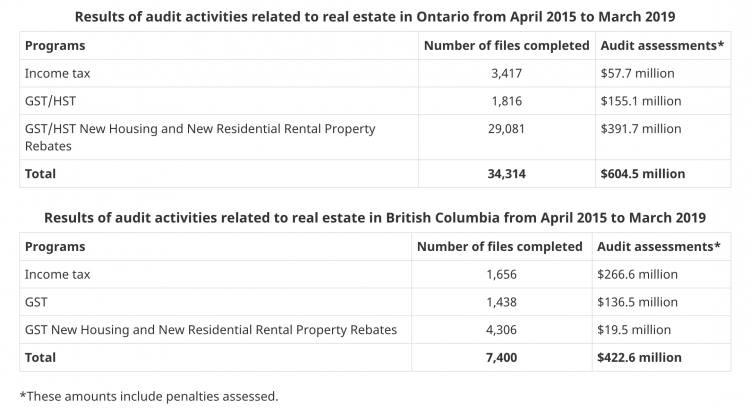

The audit program effectively targets Greater Vancouver and Greater Toronto properties. Since 2015 the CRA has identified a total of $1.02 billion from its real estate assessments, including $100.9 million from 1,896 penalties.

Whereas penalties accounted for 8.3 % of assessments in the Toronto and Vancouver region, from 2015 to 2018, they accounted for 17.7% of assessments in the first three months of 2019, when the CRA collected $30 million. Penalties are not broken down by province.

The CRA states it will apply a penalty equal to 50% of the additional tax payable if a taxpayer knowingly makes a false statement when filing a return. That means about 22% of the total assessments (or $201.8 million) derived from what auditors determined to be intentional false statements.

“The most serious cases of non-compliance are considered tax evasion, are referred for criminal investigation, and may result in criminal charges being laid,” Igolkine said.

“Once a case is analyzed in detail to determine the extent of the alleged tax offense, it is then referred to our Criminal Investigations Program for further analysis, though it is important to note that not all files will trigger a criminal investigation. Reassessments and the application of gross negligence penalties are civil outcomes of an audit, and are not considered tax evasion.”

CRA spokesperson Dany Morin said June 25 that there has been an increase in case referrals to the Public Prosecution Service of Canada, however “As the CRA investigates increasingly complex and sophisticated cases, we are experiencing more legal challenges at various points in our investigations.”

The CRA’s proactive disclosure of its audit results follow a 64% increase in Lower Mainland housing prices since 2014, while the average local wage in B.C. only increased 8.8%.

“The most innovative tax policies in ensuring transparency and accountability in B.C. real estate seems to be, in part, enforcing existing rules and ensuring that public entities like the Canada Revenue Agency are properly resourced to do their jobs – locally and internationally,” said Andy Yan, director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University, who has studied the growing gap between reported incomes and housing prices in Greater Vancouver for the past decade.

Tax collectors are getting more efficient, it appears, as the total value of 1,470 B.C. real estate assessments from April 2015 to March 2016 was only $18.5 million – that’s just $12,585 per audit.

Flynn said better data collection by the provincial government that ties homeowner information to tax returns via social insurance numbers is likely a factor.

The audits cover three specific matters: unreported income (including capital gains), GST payments on new buildings and new home GST/HST rebates.

Of the $422.6 million collected in B.C. since 2015, $266.6 million is for income, $136.5 million is for GST payments and only $19.5 million is for new home rebates.

With the 223 audits in 2019 related specifically to income, the taxman hauled in an average of $417,937 per audit.

“It makes sense you’d have more income tax per file because of the sharp rise in prices” in B.C., said Flynn.

The audits may turn up unreported income based on cross-referencing a home’s value to the owner’s reported incomes.

“The acquisition of expensive assets, such as a high-end home, without an obvious income source, can be an indicator of potential unreported income on income tax returns,” notes the CRA website.

This CRA chart shows the total audit figures since April 2015 for its real estate non-compliance program in Ontario and B.C.

Audits are also leading to checks on residency status, which trigger different reporting requirements. Residents of Canada have to report their worldwide income to the CRA whereas non-residents only have to report their Canadian-source income.

“It speaks to the need to trust but also verify our taxation policy,” Yan said.

According to Statistics Canada, non-residents (for tax purposes) own 4.9% of the region’s total housing stock outright but have a stake in 7.6%. However non-resident ownership rises to 15.6% for new condos built in 2017 and 2018.

“This is a population that doesn’t have a tax home in Canada,” said Yan.

As well, property flipping and unreported capital gains on non-primary residences are also sources of unreported income.

Flynn speculated that the CRA is catching flippers and builders who are declaring multiple homes as capital gains rather than business income, which reduces their tax bill by about 50%, assuming they are in the top income tax bracket.

The CRA has been auditing pre-sale condos, noting capital gains on assignments are taxable.

Builders and developers also represent a significant source of assessments because, according to the CRA, “the builder of a new or substantially-renovated home must collect GST/HST when the home is sold and remit that tax to the CRA.”

In Ontario, audits since 2015 turned up much more money for new home GST/HST rebates ($391.7 million) than for GST/HST payments ($155.1 million) or income ($57.7 million).

Tax lawyer Terry Barnett of Thorsteinssons LLP told Glacier Media the large number of assessments in Ontario from new home rebates compared to those in B.C. are due to two factors.

First, in B.C. the GST rebate cannot be claimed on homes over $450,000, rendering it practically useless in the Lower Mainland. Second, the HST applies in Ontario and there is no elimination of the HST rebate after its cap is reached on the first $400,000 of a new home.

“Consequently, most new home buyers in Ontario apply for the [HST] rebate,” Barnett said.

However, as the CRA notes on its website, “one of the main conditions for the new housing rebate to be available is that you must buy or build the house for use as your or your relation's primary place of residence.”

The CRA has conducted nearly five times as many audits in Ontario (34,314) than in B.C. (7,400) despite B.C. audits pulling in 10 times more money, on average.

Morin said the disparity is due to Ontario’s 29,081 HST rebate audits to date.

Flynn speculated that the CRA is attempting to capture as many taxation matters as possible.

“Maybe they’ll start looking at B.C. a bit more,” Flynn said.